TL;DR

- Malaria destroys red blood cells, leading to anemia especially in children and pregnant women.

- Plasmodium falciparum causes the most severe drop in hemoglobin.

- Prevention (bed nets, ACT) cuts both malaria cases and anemia rates.

- Diagnosis combines rapid malaria tests with hemoglobin measurement.

- Treatment includes antimalarials plus iron or blood transfusion when needed.

What Is Malaria?

Malaria is a vector‑borne disease caused by Plasmodium parasites that spreads through the bite of infected Anopheles mosquitoes. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates 229million cases worldwide in 2023, with the bulk occurring in sub‑Saharan Africa.

Understanding Anemia

Anemia is a condition where the blood lacks enough healthy red blood cells (RBCs) or sufficient hemoglobin to transport oxygen. Normal hemoglobin for adults is 13-17g/dL (men) and 12-15g/dL (women); values below these thresholds define anemia.

How Malaria Leads to Anemia

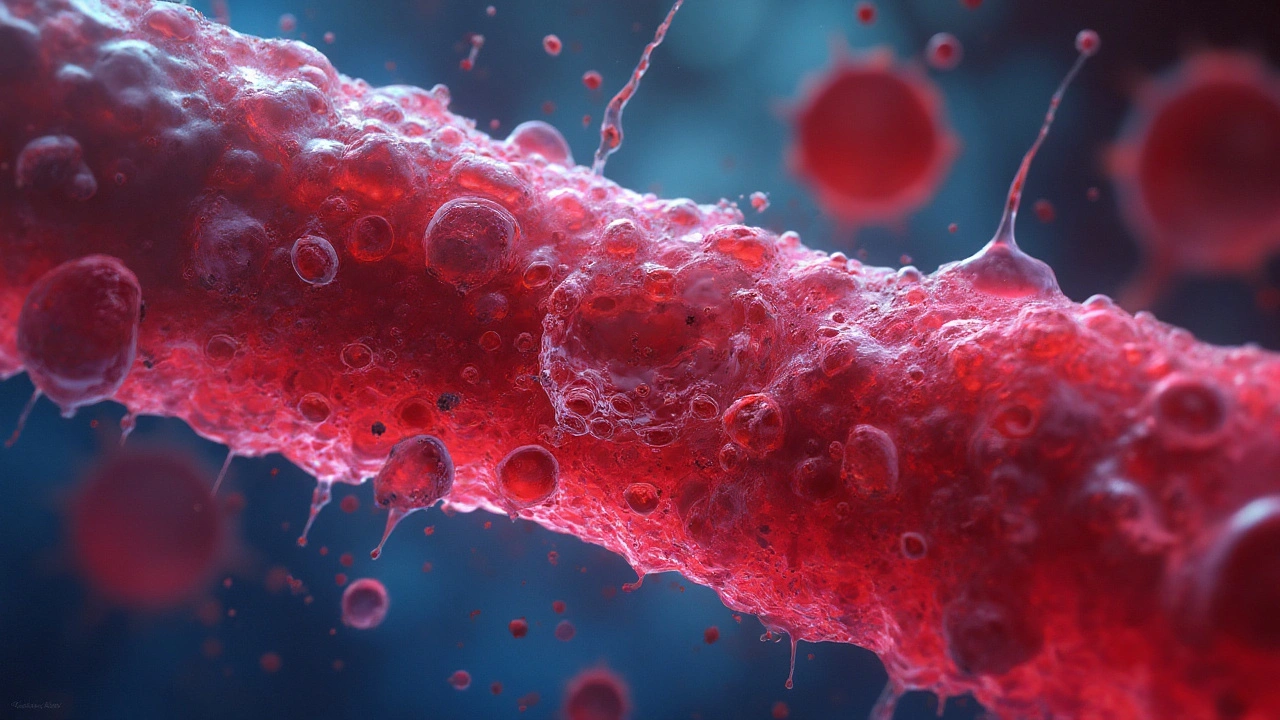

The connection hinges on three biological processes:

- Hemolysis - Each malaria cycle forces the parasite to burst the infected RBC, releasing merozoites. This rupture destroys up to 10% of the circulating RBC pool daily in severe infections.

- Bone‑marrow suppression - Inflammatory cytokines (TNF‑α, IFN‑γ) released during infection inhibit erythropoiesis, reducing new RBC production.

- Spleen sequestration - The spleen filters out both infected and partially damaged RBCs, further depleting circulating cells.

These mechanisms combine to drop hemoglobin quickly, especially in Plasmodium falciparum, the species most linked to severe anemia. Children under five and pregnant women suffer the greatest risk because they start with lower iron stores and have higher parasite loads.

Plasmodium Species and Anemia Risk

| Species | Geographic Preference | Typical Parasitemia (parasites/µL) | Risk of Severe Anemia |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmodium falciparum | Sub‑Saharan Africa, SE Asia | >100,000 | High (up to 70% of severe cases) |

| Plasmodium vivax | South America, South‑East Asia | 10,000-50,000 | Moderate (relapsing anemia) |

| Plasmodium malariae | Africa, Latin America | 2,000-5,000 | Low (chronic mild anemia) |

Who Is Most Affected?

Data from the WHO’s 2023 Global Malaria Report show:

- Children under five account for 67% of malaria‑related anemia deaths.

- Pregnant women experience a 30‑40% increase in severe anemia risk, leading to low birth weight and pre‑term delivery.

- In endemic regions, up to 45% of school‑age children have hemoglobin below 11g/dL during peak transmission season.

These figures highlight why malaria‑linked anemia is a public‑health priority, not just an occasional complication.

Diagnosing the Dual Problem

Clinicians need to confirm both infections and blood‑count status:

- Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT) - Detects Plasmodium antigens within 15minutes; sensitivity >95% for P. falciparum.

- Microscopy - Gold standard for parasite quantification and species identification.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) - Provides hemoglobin, hematocrit, and RBC indices. A hemoglobin <12g/dL in women or <13g/dL in men flags anemia.

- Reticulocyte count - Helps differentiate hemolytic anemia (high retics) from bone‑marrow suppression (low retics).

When malaria is confirmed and hemoglobin is <7g/dL, immediate treatment escalation is advised.

Treatment and Prevention Strategies

The therapeutic goal is two‑fold: eradicate the parasite and restore blood oxygen‑carrying capacity.

- Antimalarial therapy - Artemisinin‑based combination therapy (ACT) is the WHO‑recommended first‑line regimen for P. falciparum. ACT reduces parasite load within 48hours, limiting further RBC destruction.

- Iron supplementation - Oral iron (60mg elemental iron daily) is given after the acute phase, unless iron overload is a concern.

- Blood transfusion - Reserved for hemoglobin <5g/dL or symptomatic patients (e.g., severe tachycardia, respiratory distress).

- Preventive measures

- Insecticide‑treated nets (ITNs) lower malaria incidence by 50% and thus cut anemia cases in half in high‑risk villages.

- Seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) for children aged 3‑59months during peak transmission.

- Vaccination with RTS,S/AS01 (Mosquirix) - shown to reduce clinical malaria by ~30% and associated anemia episodes.

Related Concepts and Next Steps

Understanding malaria‑induced anemia opens doors to broader topics:

- Vector control - Indoor residual spraying, larval source management, and novel genetic‑engineered mosquitoes.

- Nutrition in endemic areas - Food‑based iron fortification and deworming programs that boost baseline hemoglobin.

- Health‑system strengthening - Integrated community health worker programs that combine malaria testing with anemia screening.

- Research frontiers - New antimalarial compounds targeting the parasite’s heme detoxification pathway and monoclonal antibodies against PfEMP1.

Readers interested in deeper dives might explore "Malaria Vaccines 2025", "Iron Deficiency in Sub‑Saharan Children", or "Integrated Disease Surveillance" as logical follow‑up topics.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does malaria cause anemia faster than other infections?

Malaria parasites live inside red blood cells. Every replication cycle ruptures the host cell, directly destroying RBCs. In addition, the immune response suppresses new RBC production and the spleen removes both infected and partially damaged cells. The combined effect can drop hemoglobin by several grams in a single week, far faster than most bacterial or viral illnesses.

Can iron supplements worsen malaria infection?

During active infection, high iron levels can potentially fuel parasite growth, so WHO advises postponing iron supplementation until the acute malaria episode resolves. In practice, clinicians start iron after parasite clearance or once hemoglobin stabilises.

What hemoglobin level defines severe anemia in malaria patients?

The WHO threshold for severe anemia is hemoglobin <7g/dL (or <5g/dL in pregnancy). Patients below this level usually need urgent antimalarial treatment plus supportive care, such as blood transfusion.

How effective are insecticide‑treated nets at reducing anemia?

Large cluster‑randomised trials in Tanzania and Kenya showed a 45‑55% reduction in moderate‑to‑severe anemia among children sleeping under ITNs, because fewer malaria infections translate directly into less hemolysis.

Is the malaria vaccine useful for preventing anemia?

The RTS,S/AS01 vaccine reduces clinical malaria episodes by about 30% in children aged 5‑17months. Fewer clinical episodes mean fewer bouts of hemolysis, so vaccinated children experience lower rates of severe anemia, especially during high‑transmission seasons.

All Comments

Renee Zalusky September 23, 2025

Wow, this is one of those posts that makes you realize how much we take basic biology for granted. The way malaria systematically dismantles RBCs like a microscopic demolition crew is terrifying-and elegant in a horrifying sort of way. I had no idea the spleen was basically a RBC bouncer, kicking out even the *damaged* ones. And bone marrow suppression? That’s like the body’s own immune system sabotaging its factory. Makes you wonder if we’re fighting the parasite… or just the body’s overzealous defense mechanisms.

Also, the fact that kids under five are hit so hard? That’s not just statistics-that’s a generation losing oxygen before they even learn to ride bikes. We need more than bed nets. We need *systems*.

Scott Mcdonald September 23, 2025

Hey, I just got back from a trip to Uganda last year and saw this firsthand-kids with pale lips and no energy, moms carrying them to clinics. One nurse told me they don’t even wait for the CBC anymore if the RDT’s positive and the kid’s white as a sheet. Just start the transfusion. Scary stuff. Also, the iron thing? Totally overrated. If you give iron too early during active infection, it just feeds the parasite. Gotta treat the malaria first, then fix the iron. Learned that the hard way.

Victoria Bronfman September 24, 2025

Okay but like… 🤯 the fact that P. falciparum can hit 100k parasites per microliter?? That’s like a rave in your bloodstream. 🎉🩸 And the spleen just being like ‘nah, not today’ and chowing down on RBCs?? I’m low-key obsessed with how brutal and beautiful biology is. Also, why isn’t this on TikTok?? Someone make a 15-second explainer with anime visuals and a lo-fi beat. I’d watch it 50x. 🧬💔 #MalariaAwareness #BloodCellsArePeopleToo

Gregg Deboben September 25, 2025

This is what happens when you let third-world diseases fester because ‘global health’ is some woke buzzword. We spend billions on crypto and gender pronouns while kids in Africa bleed out from a bug we’ve had a cure for since the 1940s. ACTs are cheap. Bed nets cost $2. Why isn’t the U.S. military dropping them like supplies in a war zone? Because politics. Because weakness. Because we’ve forgotten how to win. Fix the problem, not the guilt.

And stop pretending vivax is ‘mild.’ It’s not. It’s just slower at killing you. 🇺🇸

Christopher John Schell September 25, 2025

You guys are killing it with this discussion! 💪 Seriously-this is the kind of science that changes lives. Let’s not just talk about it-let’s DO something. Volunteer with a global health org. Donate to Nothing But Nets. Advocate for funding in your town hall. This isn’t just ‘medical info’-it’s a call to action. And remember: every RBC saved is a child who gets to grow up, go to school, maybe even become a doctor someday. 🌍❤️🩹 Keep spreading this knowledge. You’re making a difference!

Felix Alarcón September 25, 2025

Just wanted to add something from my time working in Colombia-P. vivax relapses are sneaky. People think they’re ‘cured’ after the fever breaks, but the hypnozoites in the liver wake up months later. That’s why we had to give primaquine even if the RDT was negative. And yeah, iron supplementation? Had to be timed right-wait 2-4 weeks after antimalarials, or you risk oxidative stress. Also, kids in rural areas often have zinc and vitamin A deficiency too, which makes anemia worse. It’s never just one thing. But hey, at least we’re talking about it now. 🙏