Antihistamine Cross-Reactivity Checker

Antihistamine Cross-Reactivity Tool

This tool helps identify potential cross-reactivity between antihistamines based on chemical structure and documented allergy cases.

Cross-Reactivity Analysis

Did you know that the very pills you reach for when you sneeze can sometimes give you a rash instead? Antihistamine allergy is a rare but real paradox where drugs meant to calm an allergic reaction end up triggering one. Below you’ll find everything you need to spot, test, and manage these reactions - from the chemistry of H1 receptors to practical tips for navigating doctors’ appointments.

What Exactly Is an Antihistamine Allergy?

Most people think of antihistamines as harmless blockers of histamine, the molecule that makes you itch and swell. In a hypersensitive patient, however, the drug can act like a faulty key that opens the H1 receptor instead of locking it. Durda et al. (2017) described a case where a woman developed urticaria after taking both first‑ and second‑generation H1 antihistamines, suggesting an “inverse agonist” turned into an “agonist” because of a possible H1‑receptor polymorphism.

H1 antihistamine is a class of drugs that bind to the histamine‑1 receptor to prevent histamine‑induced symptoms such as itching, swelling, and redness.While the majority of users experience relief, a tiny subset (estimated far below 1 %) may develop skin reactions, angio‑edema, or even anaphylaxis. The reaction can be immediate (within minutes) or delayed up to two hours after the dose.

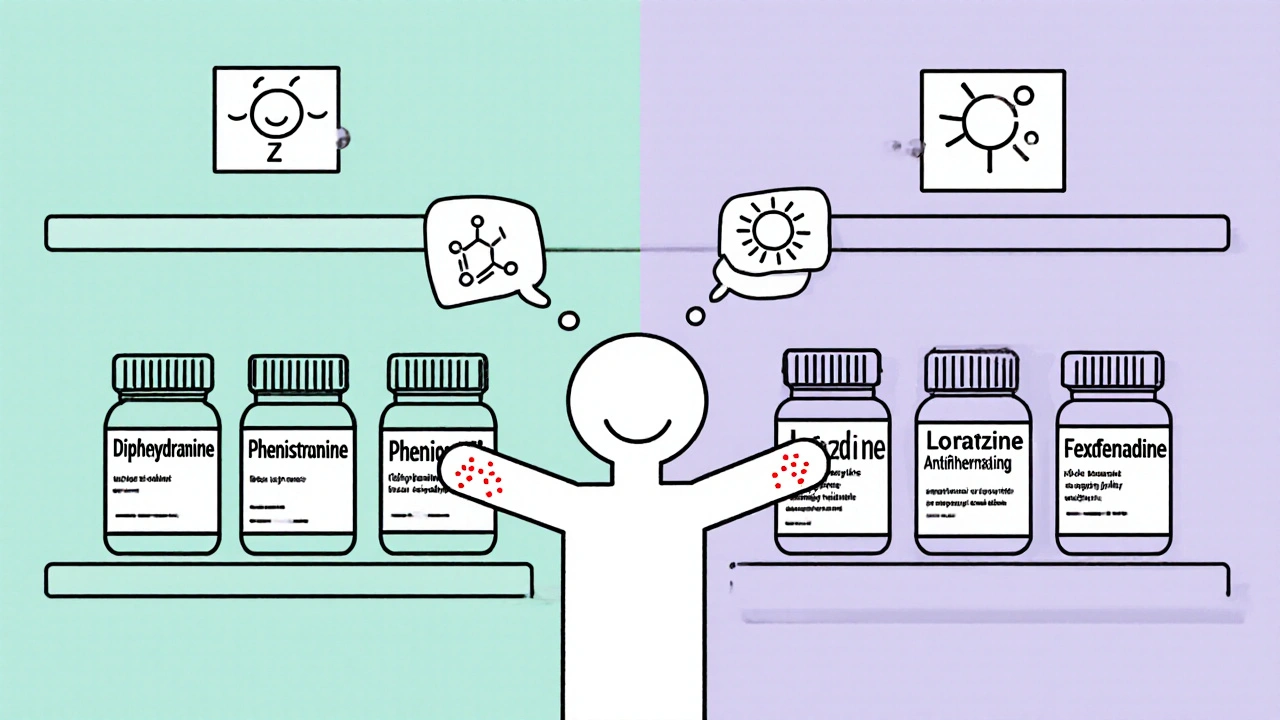

How Do First‑ and Second‑Generation Antihistamines Differ?

First‑generation drugs (diphenhydramine, pheniramine) cross the blood‑brain barrier, cause drowsiness, and have a short 4‑6 hour half‑life. Second‑generation agents (loratadine, cetirizine, fexofenadine) stay peripheral, last 12‑24 hours, and are marketed as “non‑sedating.” Yet both groups have been implicated in hypersensitivity cases.

| Feature | First‑Generation | Second‑Generation |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Examples | Diphenhydramine, Pheniramine | Loratadine, Cetirizine, Fexofenadine |

| Blood‑Brain Barrier Penetration | High - causes sedation | Low - minimal CNS effect |

| Half‑Life | 4‑6 h | 12‑24 h |

| Documented Allergy Cases (per 100 k users) | ~0.6 | ~0.3 |

| Common Chemical Classes | Piperazines, Alkylamines | Piperidines, Piperazines |

The table shows that, although second‑generation drugs are generally safer for sedation, they are not immune to rare allergic responses.

Cross‑Reactivity: Why One Drug Can Trigger Reactions to Others

Cross‑reactivity occurs when the immune system recognises similar molecular features across different antihistamines. Lee et al. (2018) reported a child reacting to both piperidine‑type (loratadine) and piperazine‑type (cetirizine) agents, even though skin prick tests were negative for one of them. The key takeaway: a negative skin test does not guarantee safety.

Cross‑reactivity the phenomenon where an allergic response to one drug also occurs with other drugs that share similar chemical structures or binding sites.Structural studies by Wang et al. (2024) revealed two ligand‑binding pockets in the H1 receptor - a deep hydrophobic cavity and a secondary site - which can accommodate diverse antihistamine scaffolds. When a patient’s antibodies target a shared motif, reactions can span multiple drug classes.

Diagnosing Antihistamine Hypersensitivity

Standard skin prick testing often falls short. In the ketotifen case, the skin test was negative but oral provocation produced a wheal at the 120‑minute mark. Oral provocation remains the gold standard, but it carries risk, so it should be performed under medical supervision.

- Step 1: Detailed drug‑history interview - note every antihistamine tried, dose, timing, and exact symptoms.

- Step 2: Skin prick or intradermal testing with the suspect drug(s). Record wheal size, but interpret cautiously.

- Step 3: Controlled oral challenge - start with a sub‑therapeutic dose, increase every 30 minutes while monitoring for cutaneous or systemic signs.

- Step 4: If a reaction occurs, document the drug, dose, and latency; refer the patient to an allergist for further work‑up.

Lab markers such as serum tryptase may help differentiate IgE‑mediated anaphylaxis from non‑IgE mechanisms, though the latter are more common in antihistamine hypersensitivity.

Managing the Condition: What to Do When You Can’t Take Antihistamines

If you’ve been diagnosed with an antihistamine allergy, avoiding the trigger is the first line of defense. Here are practical steps:

- Keep a medication diary; note any new over‑the‑counter products that contain antihistamines (e.g., cold remedies).

- Ask your pharmacist for “non‑antihistamine” alternatives for allergic rhinitis - options include nasal corticosteroids, leukotriene receptor antagonists (montelukast), or topical mast cell stabilisers.

- Treat underlying infections or chronic inflammation; Durda et al. observed symptom resolution after addressing a concurrent bacterial infection.

- Carry an emergency antihistamine‑free rescue kit - epinephrine auto‑injector if you’ve experienced systemic reactions.

- Inform every healthcare provider of your allergy; use a medical alert bracelet that lists “antihistamine hypersensitivity.”

Future Directions: Will New Antihistamines Solve This Problem?

Structural insights from cryo‑EM studies (Wang 2024) are guiding the design of next‑generation molecules that bind to the secondary H1‑receptor site. The goal is to create drugs that avoid the “active‑state stabilization” seen in hypersensitive patients. Ongoing research into H1‑receptor polymorphisms may eventually allow genetic screening before prescribing antihistamines.

Until then, clinicians rely on careful history, targeted testing, and patient education to navigate this rare but tricky side effect.

Can I develop an antihistamine allergy after years of tolerance?

Yes. Cases have been reported where patients tolerated a drug for months before suddenly reacting. Changes in immune status, infections, or new receptor polymorphisms can trigger a delayed hypersensitivity.

Are there safe antihistamines for people with cross‑reactivity?

There is no universal safe option. Some patients tolerate drugs from a chemically distinct class (e.g., a H2 antihistamine like ranitidine) or non‑antihistamine therapies. A personalized challenge test under specialist supervision is required.

What symptoms indicate an antihistamine‑triggered reaction?

Common signs include urticaria (hives), angio‑edema, facial swelling, itching, or, in severe cases, wheezing and drop in blood pressure. Skin reactions may appear minutes after the dose or be delayed up to two hours.

Should I stop using my regular antihistamine if I suspect a reaction?

Discontinue the suspected drug immediately and contact a healthcare professional. Do not switch to another antihistamine without testing, as cross‑reactivity is possible.

Is there any lab test to confirm antihistamine allergy?

Specific IgE testing for antihistamines is not widely available. Diagnosis relies on clinical history, skin testing, and controlled oral challenge. Serum tryptase can help differentiate anaphylaxis from milder reactions.

All Comments

Rhea Lesandra October 26, 2025

Keeping a medication diary is a game‑changer when you suspect an antihistamine allergy. Write down the brand, dose, and any skin or breathing changes – even the tiniest itch matters. This simple habit often reveals patterns that the doctor can use for targeted testing.

Tim Waghorn November 11, 2025

When evaluating antihistamine hypersensitivity, it is essential to distinguish between IgE‑mediated and non‑IgE mechanisms. Serum tryptase levels can provide objective data, especially in cases of systemic involvement. Moreover, the oral provocation test, while risky, remains the definitive diagnostic tool under specialist supervision. Documentation of dose, latency, and clinical manifestations should be meticulous to guide future prescribing.

Jacqui Bryant November 26, 2025

That makes sense – a clear record helps the allergist pinpoint the culprit. I’ve found simple charts work well for this.

Paul Luxford December 12, 2025

Cross‑reactivity can be tricky, especially when a patient has tolerated a drug for years and then reacts. It’s wise to discuss alternative classes like H2 antagonists with the prescribing physician.

Johnae Council December 28, 2025

Honestly, most people never think the “benign” allergy meds could bite back. If you ever get a rash after a cold pill, don’t just blame the virus – it could be the antihistamine hidden inside.

Manoj Kumar January 12, 2026

Oh, sure, because nothing says “trust the medical system” like a hidden antihistamine surprise. I guess the universe enjoys keeping us on our toes, especially when we’re half‑asleep from first‑gen diphenhydramine. At least it makes for a good story at the next dinner party.

Hershel Lilly January 28, 2026

If you suspect an antihistamine allergy, a referral to an allergist for controlled oral challenge is the safest route. They can also explore genetic testing for H1‑receptor polymorphisms, which might explain delayed reactions.

Carla Smalls February 12, 2026

Going to a specialist is the right move – they’ll have the tools you need. Stay positive; many patients find safe alternatives after proper testing.

Monika Pardon February 28, 2026

Of course, the “antihistamine‑free” world will arrive as soon as the moon aligns with Mars. Until then, keep that bracelet shiny.