When you start an antibiotic for a sore throat or a sinus infection, you expect to feel better. But what if, a few days in, you start having watery diarrhea, cramps, and fever? It’s not just a side effect. It could be Clostridioides difficile - a dangerous infection that’s become one of the most common causes of hospital-acquired diarrhea in the U.S. and beyond. Every year, nearly half a million people in the United States get infected. Many of them are older adults, and some don’t survive. The good news? Most cases are preventable - if you know what to look for and how to stop it.

What Exactly Is Clostridioides difficile?

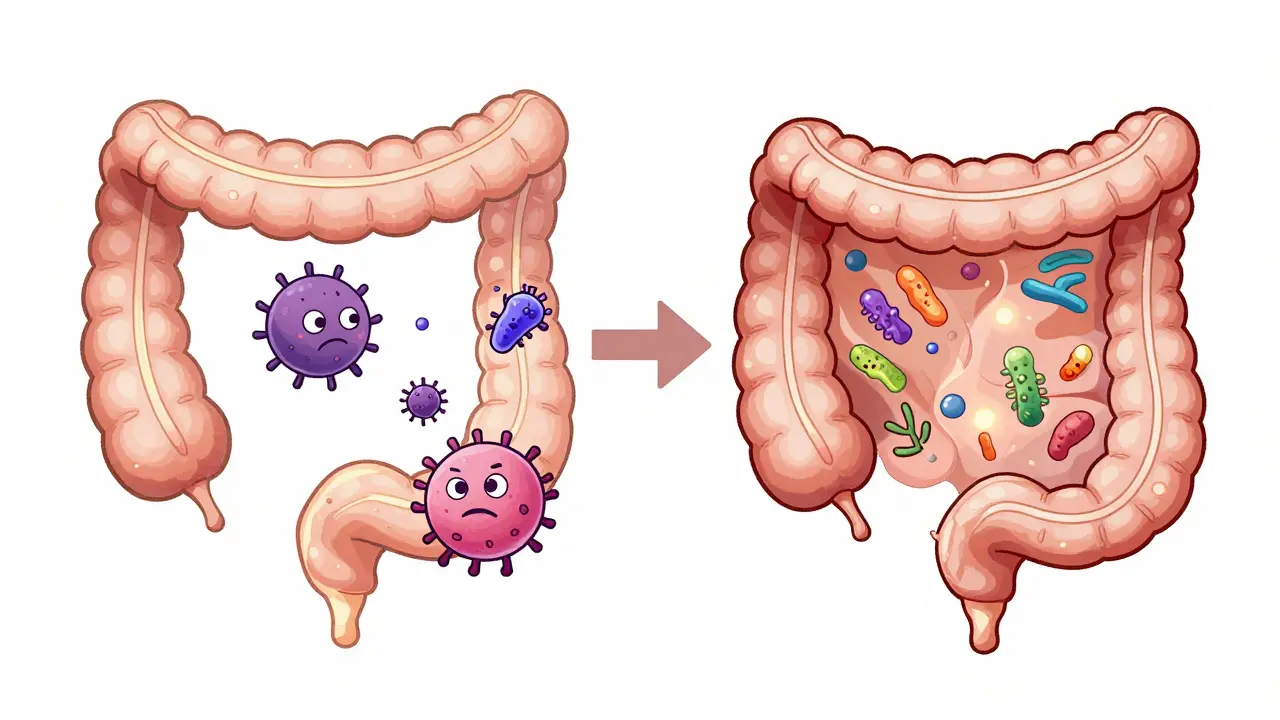

Clostridioides difficile, often called C. diff, is a bacterium that lives harmlessly in the gut of some people - but when the balance of gut bacteria gets thrown off, it can take over. This usually happens after antibiotics wipe out the good bacteria that normally keep C. diff in check. Once it spreads, C. diff releases toxins that attack the lining of the colon, causing inflammation, severe diarrhea, and sometimes life-threatening colitis.

The infection isn’t new. Doctors first noticed it in the 1970s after a spike in cases linked to clindamycin. Since then, it’s evolved. New strains like NAP1/027 produce more toxins and form tougher spores that survive for months on surfaces - doorknobs, bed rails, toilets - even after cleaning. These spores are what make C. diff so hard to control in hospitals and nursing homes.

How Do You Get It?

The main way C. diff spreads is through the fecal-oral route. Someone with the infection doesn’t wash their hands properly after using the bathroom. They touch a surface. The next person touches that same surface, then touches their mouth. That’s it. You don’t need to be in a hospital to catch it - community cases are rising. But your risk jumps sharply if you’ve recently taken antibiotics, especially fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins, or clindamycin.

Other risk factors include:

- Being over 65 years old - 80% of cases happen in this group

- Staying in the hospital for more than a week - each extra day raises your risk by about 1.5%

- Having inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which increases your risk over fourfold

- Undergoing gastrointestinal surgery

- Taking proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for acid reflux - they may alter gut acidity and make infection easier

It’s also possible to carry C. diff without symptoms. Up to 50% of hospitalized patients have it in their gut without getting sick. But if their immune system weakens or they get another round of antibiotics, the infection can suddenly flare up.

What Are the Symptoms?

The most common sign is watery diarrhea - three or more loose stools a day for at least two days. But it’s not always that simple. Some people have mild cramping. Others develop severe pain, fever, nausea, loss of appetite, and bloody stools. In the worst cases, the colon swells dangerously, leading to perforation, sepsis, or death.

Here’s the tricky part: C. diff symptoms can look like food poisoning, a stomach virus, or even a normal reaction to antibiotics. That’s why many people ignore it until it’s too late. If you’re on antibiotics and start having diarrhea - even if it’s just a little - don’t brush it off. Talk to your doctor.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Testing isn’t straightforward. You can’t just test stool and get a clear answer. C. diff can be present without causing disease. So labs use a two-step process: first, a test for glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH), a protein the bacteria produce. If that’s positive, they follow up with a toxin test or a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) to confirm active infection.

But even then, results can be misleading. Some tests miss the infection - false negatives happen in 10-30% of cases. That’s why doctors rely on symptoms too. If you have diarrhea, recent antibiotics, and a positive test, it’s likely C. diff. If you have no symptoms but test positive, you’re probably just colonized - not infected - and don’t need treatment.

Treatment: What Works Now?

For years, metronidazole was the go-to drug. But it’s no longer recommended. Studies showed it fails more often than newer options and increases the chance of recurrence. Today, guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American College of Gastroenterology point to two main treatments:

- Fidaxomicin - 200 mg twice daily for 10 days. This drug kills C. diff without wiping out other gut bacteria as much. It reduces recurrence by nearly half compared to vancomycin.

- Vancomycin - 125 mg four times a day for 10 days. Still effective, but less so than fidaxomicin at preventing relapse.

For people who have had multiple recurrences - and about 20-30% of patients do - standard antibiotics often fail. That’s where fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) comes in. FMT restores healthy gut bacteria by transferring stool from a healthy donor. Success rates? 85-90%. That’s better than any antibiotic. The FDA now allows FMT under an enforcement discretion policy for recurrent C. diff, making it more accessible.

In 2023, the FDA approved a new treatment called SER-109 - a purified, spore-based microbiome therapy. In clinical trials, it prevented recurrence in 88% of patients over eight weeks. It’s not a transplant, but it works the same way: repopulating the gut with good bacteria.

Why Probiotics Don’t Work for Prevention

For years, doctors told people to take probiotics like Lactobacillus or Saccharomyces boulardii while on antibiotics to prevent diarrhea. But a 2022 Cochrane review of 39 studies - involving nearly 10,000 people - found no strong evidence that probiotics prevent C. diff. They might slightly reduce general antibiotic-associated diarrhea, but not C. diff specifically. The American College of Gastroenterology now advises against using them for C. diff prevention. The science just isn’t there.

How to Prevent It

Prevention is the most powerful tool we have. And it starts with antibiotics.

1. Use antibiotics only when necessary. Many sinus infections, ear infections, and bronchitis cases are viral. Antibiotics won’t help - but they can trigger C. diff. Ask your doctor: "Is this really bacterial? Are there other options?"

2. Practice strict hand hygiene. Soap and water work. Alcohol-based hand sanitizers don’t kill C. diff spores. Wash your hands thoroughly after using the bathroom and before eating - especially in hospitals or care homes.

3. Clean surfaces properly. Standard cleaners won’t do it. You need EPA-registered disinfectants on List K - those with bleach or hydrogen peroxide. Hospitals use them on bedrails, toilets, and doorknobs. At home, if someone has C. diff, clean bathrooms daily with bleach-based products.

4. Use contact precautions in hospitals. If you or a loved one is infected, the hospital should put you in a private room, give you your own toilet and equipment, and have staff wear gloves and gowns. These steps cut transmission by 40-50%.

5. Avoid unnecessary PPIs. If you’re on acid reflux medication long-term, talk to your doctor about whether you still need it. Reducing PPI use lowers C. diff risk.

What’s Next for C. diff?

Research is moving fast. Scientists are developing vaccines to prevent infection in high-risk groups. New targeted antibiotics are being tested to spare healthy gut bacteria. Microbiome therapies like SER-109 are becoming standard. And hospitals are finally taking antibiotic stewardship seriously - reducing unnecessary prescriptions, tracking infection rates, and training staff.

But progress depends on awareness. Too many people still think diarrhea from antibiotics is normal. It’s not. It’s a warning sign. And every time we choose the right antibiotic - or skip it altogether - we protect not just ourselves, but our families and communities.

When to See a Doctor

Call your healthcare provider if you’re on antibiotics and experience:

- Three or more loose stools per day for two or more days

- Severe abdominal pain or cramping

- Fever above 101°F (38.3°C)

- Bloody stools

- Nausea, vomiting, or loss of appetite

Don’t wait for it to get worse. Early treatment saves lives.

Can you get C. diff without taking antibiotics?

Yes, but it’s rare. Most cases are linked to antibiotic use. However, community-acquired C. diff is increasing. People without recent antibiotics can get infected through contaminated surfaces, especially in places like nursing homes or daycare centers. Older adults and those with weakened immune systems are most at risk.

Is C. diff contagious?

Absolutely. C. diff spreads through spores in feces. If someone with the infection doesn’t wash their hands well, they can leave spores on surfaces. Others touch those surfaces and then touch their mouth. That’s how it spreads - even in homes and public places. Proper handwashing with soap and water is the best defense.

How long does C. diff last after treatment?

Symptoms usually improve within a few days of starting treatment. But the infection can come back. About 20-30% of people have a recurrence after treatment, and some have multiple recurrences. That’s why fidaxomicin and FMT are preferred - they reduce relapse. Even after symptoms go away, spores can linger in the gut for weeks, so hygiene remains critical.

Can C. diff cause long-term damage?

In severe cases, yes. Toxic megacolon, colon perforation, and sepsis can occur. Even after recovery, some people develop chronic diarrhea or ongoing gut dysfunction. Recurrent infections can lead to repeated hospital stays, loss of quality of life, and increased risk of death - especially in older adults. Early diagnosis and proper treatment reduce these risks.

Are there any home remedies for C. diff?

No. There are no proven home remedies. Rest, fluids, and avoiding anti-diarrheal drugs like loperamide (Imodium) are advised, but they don’t treat the infection. C. diff requires medical treatment with specific antibiotics or FMT. Delaying care can lead to serious complications. Always consult a doctor if you suspect C. diff.

Can you get C. diff more than once?

Yes. About 20-30% of people have a recurrence after their first infection. If you’ve had one recurrence, your chance of another jumps to 40-60%. That’s why treatment choices matter - fidaxomicin and FMT are better at preventing repeat infections than vancomycin or metronidazole.

All Comments

Emma Hooper December 30, 2025

Okay but can we talk about how wild it is that we still treat C. diff like it’s just a bad stomach bug? I had a friend in the ICU last year - went in for a simple gallbladder thing, came out with a 10-day hospital stay, a feeding tube, and a new fear of hospitals. It’s not ‘side effects’ - it’s a silent killer wearing a lab coat. And no, probiotics aren’t magic fairy dust. Stop buying them like they’re candy.

Martin Viau January 1, 2026

Typical American medical overreach. We prescribe antibiotics like they’re vitamins, then act shocked when the microbiome implodes. In Canada, we at least have stricter stewardship protocols. You want to reduce C. diff? Stop letting every 14-year-old with a sniffle get amoxicillin. Also - bleach is still the best disinfectant. Don’t let corporate sanitizers fool you.

Marilyn Ferrera January 3, 2026

Diarrhea ≠ C. diff. But diarrhea + antibiotics? That’s a red flag. Always. Don’t wait. Don’t self-diagnose. Call your doctor. And if they dismiss you? Get a second opinion. Your gut isn’t a suggestion box.

Deepika D January 3, 2026

Let me tell you something - I’m a nurse in Mumbai, and we’re seeing more and more C. diff cases now, even outside hospitals. People think it’s just a Western problem, but no - globalization, overuse of antibiotics in livestock, and poor sanitation in urban slums are making this a global crisis. We need education, not just meds. My aunt got it after a course of cipro for a urinary infection - she was 72, no hospital stay, just bought meds over the counter. That’s the new normal. We need community health workers going door to door teaching handwashing. Not just posters. Real, human-to-human teaching. And yes, FMT works - I’ve seen it. My cousin had five recurrences. After FMT? He’s back to gardening. No more IVs. No more fear. This isn’t sci-fi. It’s medicine.

Branden Temew January 4, 2026

So… we’ve got a superbug that thrives because we treat every cold like a war zone, then we fix it with a poop transplant? That’s the future? I’m not mad… I’m just impressed. Also, SER-109? Sounds like a new Marvel villain. ‘Behold! The Spore of Doom!’

Frank SSS January 4, 2026

Y’all are acting like this is some new revelation. I’ve been telling people for years: antibiotics are a sledgehammer to a fly. And now we’re shocked the fly came back with a flamethrower? Also, PPIs? Yeah, they’re basically C. diff’s VIP lounge. Stop taking them like they’re multivitamins. And no, your ‘gut health’ tea isn’t helping. Drink water. Wash hands. Stop Googling symptoms at 2 a.m.

Paul Huppert January 6, 2026

I had C. diff after my knee surgery. Didn’t even know it until I couldn’t stop peeing. The worst part? No one took it seriously until I was vomiting blood. Just… be loud. Be annoying. Demand a test. You’re not being dramatic - you’re saving your colon.

Hanna Spittel January 7, 2026

Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know this… but bleach is cheaper than their $2k pills 😏 #CdiffTruth #FMTIsTheRealCure

Brady K. January 8, 2026

Let’s be real - the entire medical system is designed to profit from recurrence. Why would they want you cured permanently? FMT? SER-109? Cool. But they’re not pushing them hard enough. Why? Because a $50,000 transplant doesn’t scale like a $300 antibiotic script. We’re being monetized while our guts rot. Wake up.

Kayla Kliphardt January 9, 2026

Wait - so if I’m colonized but asymptomatic, I’m just… a carrier? Like a walking time bomb? That’s terrifying. Do I tell my family? My coworkers? Do I get tested every time I take an antibiotic? This is… a lot.

anggit marga January 10, 2026

You Americans always make everything about hospitals and antibiotics. In Nigeria we have no antibiotics at all. We use herbs and prayer. C. diff? We don’t have it. You created this problem by trusting pills over nature

Joy Nickles January 12, 2026

ok so i just got back from the hospital and i think i have c diff??? i took amoxicillin for 5 days and now i have 7 poops a day and my stomach feels like its on fire??? but the dr said it’s just ‘gut sensitivity’?? can someone help me??? i’m scared i’m gonna die??

Robb Rice January 13, 2026

Thank you for this comprehensive overview. I’ve worked in infection control for 18 years, and I’ve seen this evolution firsthand. The shift from metronidazole to fidaxomicin was long overdue. The real victory? Antibiotic stewardship programs that actually enforce guidelines. Not just posters. Real audits. Real consequences. We’ve cut our C. diff rates by 62% in our facility since 2020. It’s possible. It’s just hard.

Harriet Hollingsworth January 14, 2026

So… you’re telling me that people who take acid reflux meds are basically inviting a killer bacteria into their gut? And doctors keep prescribing them anyway? That’s not negligence - that’s criminal. Someone should sue. Someone should go to jail. This isn’t a medical issue. It’s a moral failure.