When you need hemodialysis, your blood needs a reliable way to leave your body, get cleaned, and return. That’s where dialysis access comes in. It’s not just a tube or a needle site-it’s your lifeline. And not all access types are created equal. The choice you make-or that your doctor recommends-can affect how often you get sick, how long you stay in the hospital, and even how long you live. There are three main types: arteriovenous (AV) fistulas, AV grafts, and central venous catheters. Each has pros, cons, and specific care rules. Knowing the difference isn’t just helpful-it’s life-saving.

Why AV Fistulas Are the Gold Standard

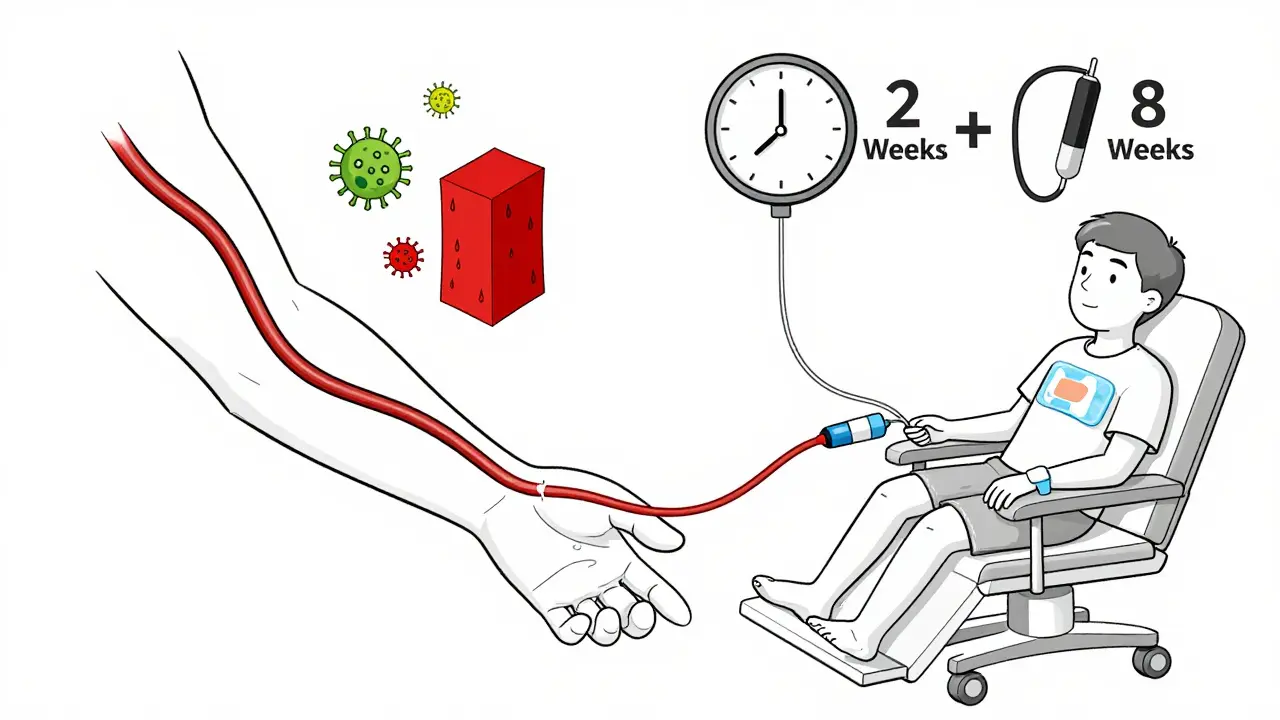

An AV fistula is made by surgically connecting an artery directly to a vein, usually in your forearm. This isn’t a quick fix. It takes 6 to 8 weeks for the vein to grow bigger and stronger so it can handle the needles used during dialysis. But that wait pays off. Fistulas last for decades. They’re less likely to clot, less likely to get infected, and far more durable than the other options. The National Kidney Foundation calls them the gold standard for a reason: they reduce your risk of death by up to 30% compared to catheters.Patients who use fistulas often report fewer hospital visits and better quality of life. One person at Azura Vascular Care had their fistula working perfectly for seven years with nothing but routine check-ups. That’s the kind of reliability you want when you’re on dialysis three times a week, every week.

But fistulas aren’t perfect. About 30% to 60% of them don’t mature properly, especially in older adults or people with diabetes. That’s why doctors do a vein mapping scan first-a simple ultrasound that checks if your blood vessels are strong enough. If your veins are too small or weak, a fistula might not be possible. That’s when you move to the next option.

When Grafts Are the Best Alternative

If your veins aren’t up to the job, an AV graft is the next best thing. Instead of using your own blood vessels, a synthetic tube-usually made of polytetrafluoroethylene-is placed between an artery and a vein. The big advantage? Healing time is shorter. You can start dialysis in just 2 to 3 weeks.But grafts come with trade-offs. They’re more prone to clotting and infection than fistulas. About 30% to 50% of grafts need some kind of intervention within the first year. That might mean a procedure to clear a clot or repair a narrowed area. Over time, most grafts need to be replaced every 2 to 3 years.

Still, for people who can’t get a fistula, grafts are a solid bridge. They’re easier to access than catheters, don’t require daily sterile care, and have better survival rates than catheters. Patients often say grafts feel more like a permanent solution than a temporary one. But they still need regular monitoring. Your dialysis team will check for the “thrill”-a buzzing sensation you can feel over the graft-that tells you blood is flowing properly.

The Reality of Catheter Use

Central venous catheters are the quickest option. They’re soft tubes inserted into large veins in your neck, chest, or groin. You can start dialysis the same day. That’s why they’re often used in emergencies. But they’re meant to be temporary. Using a catheter long-term is risky.Studies show catheter users have a 53% higher risk of death than fistula users. Why? Infections. Catheters are a direct path for bacteria into your bloodstream. The rate of fatal infections is more than double compared to fistulas. Every time you shower, you have to cover the catheter with plastic to keep it dry. Swimming, baths, even heavy sweating can become dangerous. Many patients say it limits their freedom more than anything else.

Even with strict cleaning routines, catheter-related bloodstream infections happen in 0.6 to 1.0 cases per 1,000 catheter days. That adds up fast when you’re on dialysis for years. And every infection can mean a hospital stay, antibiotics, or worse.

Some patients end up stuck with catheters because they can’t get a fistula or graft. But that shouldn’t be the default. If you’re on a catheter for more than a few weeks, talk to your doctor about your options. There’s almost always a better long-term solution.

How to Care for Your Access

No matter what type of access you have, daily care matters. But the level of care changes drastically.With a fistula, your job is simple: check for the thrill every day. Use your fingertips to feel for a gentle vibration. If it’s gone, call your dialysis center immediately-it could mean a clot. Wash your access arm with soap and water before each treatment. Don’t let anyone take your blood pressure or draw blood from that arm. Wear loose sleeves. Never sleep on that arm.

Grafts need the same vigilance. Feel for the thrill. Watch for redness, swelling, or warmth. Any sign of infection? Don’t wait. Call your team. Grafts are more likely to narrow or clot, so you may need more frequent ultrasounds or interventions.

Catheters demand the most work. You need to clean the exit site daily with antiseptic. Change the dressing exactly as your nurse shows you-usually every time you dialyze or if it gets wet or dirty. Never touch the catheter ends. Always use sterile gloves and technique. If you see pus, fever, or chills, go to the ER. This isn’t something you can ignore.

Everyone with dialysis access should get trained. Most people need 2 to 3 sessions with a dialysis nurse to learn how to care for their access. Don’t skip this. Patients who get proper education have 25% fewer complications in their first year.

What’s Changing in Dialysis Access

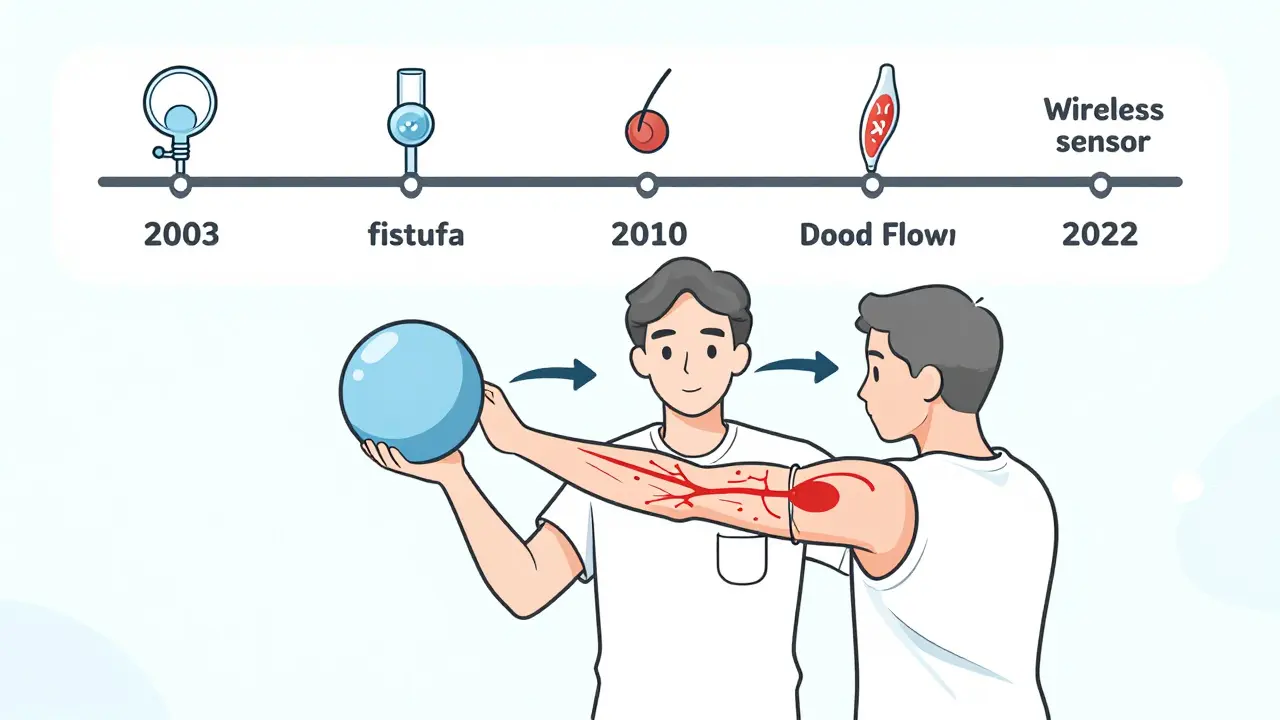

The field is moving fast. In 2022, the FDA approved the first wireless sensor for monitoring fistula blood flow-Manan Medical’s Vasc-Alert. It alerts you and your care team if flow drops, helping prevent clots before they happen. Clinical trials showed a 20% drop in thrombosis events.Preoperative exercise is another game-changer. Simple arm exercises like squeezing a ball or lifting light weights before surgery can boost fistula maturation rates by 15% to 20%. That’s huge for people with diabetes or older adults whose vessels are less responsive.

On the horizon are bioengineered blood vessels. Humacyte’s human acellular vessel is in phase 3 trials. It’s made from donor tissue stripped of cells, so your body doesn’t reject it. Early results show promise for patients with no usable veins at all.

But the biggest challenge isn’t technology-it’s equity. Black patients are 30% less likely to get fistulas than white patients, even when their medical needs are the same. That gap persists despite decades of awareness. If you’re a patient or caregiver, ask: “Why isn’t a fistula being offered?”

What to Ask Your Doctor

Don’t assume your access plan is set in stone. Here are five questions to ask at your next appointment:- Is my vein mapping done? Can I see the results?

- Why are you recommending this type of access over others?

- What’s my risk of infection or clotting with this option?

- What signs should I watch for at home?

- What’s the backup plan if this access fails?

These questions give you control. Dialysis access isn’t just a medical procedure-it’s a daily reality. You deserve to understand it fully.

The Bigger Picture

The Fistula First Breakthrough Initiative pushed fistula use from 32% in 2003 to over 60% by 2010. That’s progress. But 20% of patients still rely on catheters. That’s 20% too many. Every catheter used long-term costs the system about $15,000 more per year than a fistula. The U.S. could save $1.1 billion annually if everyone who could get a fistula did.It’s not just about money. It’s about survival. The data is clear: fistulas save lives. Grafts are a good second choice. Catheters are a last resort.

As the dialysis population ages and diabetes rates climb, we’ll need better tools. But the most powerful tool you have right now is knowledge. Know your access. Care for it. Ask questions. Push for the best option-not just the quickest one.

What’s the difference between an AV fistula and an AV graft?

An AV fistula is made by connecting your own artery and vein directly. It takes 6-8 weeks to mature but lasts for decades with proper care. An AV graft uses a synthetic tube to connect the artery and vein. It heals faster (2-3 weeks) but is more prone to clotting and infection, and usually needs replacement every 2-3 years.

Can I swim with a dialysis catheter?

No. Catheters must stay completely dry to prevent infection. Swimming, soaking in a tub, or even heavy sweating can introduce bacteria. You’ll need to cover the catheter with waterproof dressing or avoid water entirely. If you want to swim, switching to a fistula or graft is strongly recommended.

How do I know if my fistula is working?

Feel for a ‘thrill’-a gentle buzzing or vibration-over the fistula site using your fingertips. You should feel it every day. If it disappears, or if you notice swelling, pain, or coolness in your hand, call your dialysis center right away. It could mean a clot.

Why do some people need a catheter long-term?

Some patients can’t get a fistula or graft because their blood vessels are too small, damaged, or blocked by disease-common in people with diabetes or advanced age. Others may have had multiple failed access attempts. While catheters are meant to be temporary, they’re sometimes used permanently when no other option is viable. But they carry higher risks, and your care team should always be working toward switching you to a better access.

How can I reduce my risk of infection with any access type?

Wash your access site daily with soap and water. Never touch the access unless your hands are clean. Avoid wearing tight clothing or jewelry over the site. Don’t let anyone take your blood pressure or draw blood from that arm. Follow your nurse’s exact instructions for dressing changes, especially with catheters. Report redness, warmth, swelling, or fever immediately.

Is it true that exercise can help my fistula work better?

Yes. Studies show simple arm exercises-like squeezing a soft ball or doing light wrist curls-before fistula surgery can increase maturation rates by 15% to 20%. It helps strengthen blood vessels and improve blood flow. Ask your doctor or vascular surgeon for a recommended exercise plan.

What Comes Next?

If you’re on dialysis, your access is your most important tool. Don’t wait until something goes wrong to learn about it. Start today: ask for your vein mapping results, learn how to check your thrill, and talk to your care team about your long-term plan. If you’re a caregiver, be the one who asks the tough questions. If you’re newly diagnosed, don’t settle for the first option you’re given. Push for the one with the best chance of keeping you healthy for years.The future of dialysis access is brighter than ever-with better sensors, better grafts, and better outcomes. But none of that matters if you don’t know how to care for what you’ve got. Your access isn’t just a medical device. It’s your connection to life. Treat it like it.

All Comments

John Ross January 4, 2026

Let’s cut through the noise: AV fistulas aren’t just ‘gold standard’-they’re the only medically defensible option for chronic dialysis. Grafts are a Band-Aid on a hemorrhage, and catheters are walking sepsis packages. The data’s been clear since 2003: fistula utilization correlates directly with survival. Yet we still see 20% of patients stuck with central lines because of systemic inertia, not clinical necessity. Vascular access isn’t a ‘choice’-it’s a protocol. If your nephrologist isn’t pushing fistula-first with vein mapping, you’re being failed. Period.

And don’t get me started on the equity gap. Black patients are systematically steered toward catheters due to implicit bias, not anatomy. That’s not medicine-that’s structural violence. We need mandatory access planning audits in every dialysis center. No more ‘we tried’ excuses.

Also, the Vasc-Alert sensor? Brilliant. But it’s a bandage on a broken system. We need reimbursement reform that incentivizes preemptive vascular surgery, not reactive catheter maintenance. $1.1 billion saved annually? That’s not savings-that’s justice.

Exercise pre-op? Absolutely. Ball squeezes, wrist curls, resistance bands-do them for 6 weeks before surgery. It’s not ‘alternative medicine,’ it’s hemodynamic preconditioning. Your vasculature isn’t passive-it’s adaptive. Train it like you’d train a muscle.

And for god’s sake, stop calling catheters ‘temporary.’ If you’re on one longer than 30 days, your care team is failing you. Demand a fistula. Demand a graft. Demand better.

Stop accepting the minimum. You’re not a patient-you’re a survivor. Act like it.

Clint Moser January 6, 2026

wait so u mean to say theyre not putting microchips in our arms to track us?? cuz i swear i saw a doc in a video sayin the grafts are part of the CDCs new biometric surveilance program… and why do they always use that blue tubing?? its like theyre trying to make us look like cyborgs for the new world order… also my cousin got a catheter and now his blood is all purple?? i think its the fluoride in the dialysis fluid… theyre poisoning us slowly…

also why dont they just use the new bioengineered vessels from humacyte? its like they dont want us to live… its all about profit…

and the thrill? i think thats just the vibration from the satellite they implanted in my spine…

someone help me…

Aaron Mercado January 6, 2026

HOW. DARE. YOU. suggest that catheters are ‘sometimes necessary’?!?!?!! This is the most dangerous, irresponsible, and morally bankrupt medical advice I’ve ever seen in my life. Every single catheter placement is a death sentence waiting to happen. Every. Single. One. And yet, hospitals are still using them like they’re disposable razors?!?!!

And who approved this article?!? The National Kidney Foundation? The same organization that takes Big Pharma money?!? Don’t believe the ‘gold standard’ propaganda. Fistulas are a scam. They’re expensive. They require ‘vein mapping’-which is just another way to bill you $2,000 for a 10-minute ultrasound.

And don’t even get me started on ‘exercise.’ Who told you that squeezing a stress ball fixes your veins?!? That’s not science-that’s cult behavior. You’re being manipulated into thinking you’re ‘in control’ when you’re just a pawn in a billion-dollar industry that profits from your suffering.

They want you to think you have a choice. You don’t. They’ve already decided your fate. And they’re not telling you the truth. The real reason catheters are used? Because they’re easier to monitor. Because they’re easier to control. Because they’re easier to bill. And because you’re too tired to fight back.

Wake up. Your access isn’t your lifeline. It’s your leash.

Vikram Sujay January 7, 2026

Thank you for this meticulously composed and clinically grounded exposition. It is rare to encounter such a balanced and evidence-based overview in public discourse, particularly regarding chronic care modalities that are so deeply entwined with socioeconomic disparity.

I find it profoundly moving that you have underscored the human dimension-not merely the anatomical or procedural-but the existential weight carried by patients who must navigate this reality daily. The distinction between ‘temporary’ and ‘permanent’ access is not merely clinical; it is a reflection of dignity.

It is also worth noting that the cultural and institutional inertia you describe-particularly regarding racial disparities in access planning-is not unique to the United States. In India, where I reside, access to even basic vascular surgery remains unevenly distributed, and many patients are forced into catheter dependency due to systemic underfunding and lack of specialist training.

May I humbly suggest that future initiatives consider integrating community health workers into preoperative education? In our context, trust is often built not by physicians alone, but by those who walk alongside patients through the long, lonely road of dialysis. Knowledge is power, yes-but so is companionship.

With profound respect for your work.

Jay Tejada January 7, 2026

bro i had a graft for 3 years and honestly? it was kinda chill. yeah it clotted twice but the doc just zapped it with a little balloon thingy and boom-back to normal. no big deal.

my cousin’s fistula? took 10 weeks to heal and she still couldn’t feel the thrill. said it felt like her arm was asleep all the time. she ended up switching to a graft anyway.

and catheters? yeah they’re gross. but if you’re on dialysis because you got diabetes from eating tacos every day… maybe don’t act like you’re some martyr because you gotta cover your tube in plastic.

also, who the hell has time to squeeze balls before surgery? i was in the ER with a creatinine of 14. they said ‘here’s a catheter’ and i said ‘cool, thanks.’

stop making this sound like a superhero origin story. it’s just medicine. sometimes you get lucky. sometimes you don’t.

Shanna Sung January 9, 2026

They’re lying. Fistulas are a trap. They want you to think you’re getting the ‘best’ option but they’re actually using your veins as test subjects for new surgical protocols. The ‘thrill’? That’s not blood flow-that’s the frequency of the implant tracking device they put in during surgery. The ultrasound mapping? It’s not checking your veins-it’s scanning your DNA for predispositions to kidney failure so they can sell you insurance later.

And why do they never mention the 12,000 patients who died from ‘complications’ after fistula creation? Because it’s buried in the fine print. The FDA approved Vasc-Alert? It’s a prototype for the next phase of the National Health Registry. They’re building a database of every dialysis patient on Earth. You’re not a patient-you’re a data point.

And don’t get me started on ‘pre-op exercise.’ That’s just a way to get you to pay for personal training. They know you’re desperate. They’re milking you.

Ask yourself: Who profits when you’re stuck on a catheter? The hospitals? The device makers? Or someone… higher?

Don’t let them make you complicit in your own surveillance.

Allen Ye January 9, 2026

Let’s reframe this not as a medical hierarchy but as a philosophical inquiry into the nature of bodily autonomy in a system that commodifies survival.

The AV fistula, in its elegant biological simplicity-a direct arterial-venous anastomosis-is not merely a clinical tool; it is a metaphor for resilience. It is nature’s own engineering: no synthetic materials, no foreign bodies, no artificial interfaces. Just blood, pressure, and time. It asks for patience, for discipline, for reverence.

Contrast that with the graft: a synthetic tube, a technological compromise, a temporary patchwork of polymer and desperation. It speaks to our impatience as a species-we want solutions now, not in six weeks. We want convenience over longevity.

And the catheter? That is the ultimate surrender. A direct conduit to the bloodstream, a violation of the body’s natural boundaries, a constant invitation to infection. It is not merely a medical device-it is a symbol of systemic failure. Of institutional neglect. Of the quiet, unspoken truth that some lives are deemed less worthy of investment.

So when we talk about access, we are not talking about veins. We are talking about value. Who gets the gold standard? Who gets the compromise? Who gets the last resort?

And more importantly-who decides?

This isn’t just dialysis. It’s ethics in motion.

mark etang January 11, 2026

As a certified dialysis nurse with over 18 years of frontline experience, I can confirm with absolute certainty that the information presented here is clinically accurate and aligned with current best practices endorsed by the CDC, ASN, and NKF.

Our facility has reduced catheter use from 28% to 9% in five years through structured access planning, mandatory vein mapping, and patient education programs. The reduction in catheter-related bloodstream infections was dramatic-down 72%. Hospitalizations dropped by 41%. Mortality decreased by 23%.

We train every patient personally. We provide laminated cards with thrill-check instructions. We follow up weekly. We do not accept ‘I don’t understand’ as an answer.

This is not theory. This is practice. And it saves lives.

To patients: You are not alone. Your care team is fighting for you. Ask the five questions. Demand the mapping. Learn the thrill. Your access is your lifeline. Treat it like your most valuable possession-because it is.

josh plum January 11, 2026

Oh wow, look at this-someone actually wrote a sensible article about dialysis. Imagine that. Who would’ve thought? Probably someone who’s never had to sit through 12 hours of dialysis three times a week while their body turns to jelly.

Let me guess-you’re one of those people who thinks ‘just get a fistula’ solves everything? Good luck with that when you’re 72, diabetic, and your veins are thinner than cigarette paper. My uncle got a fistula, it never matured, and then they tried a graft. It clotted in three weeks. Then he got a catheter. Guess what? He’s still alive. Four years later.

So don’t come at me with your ‘gold standard’ nonsense. Not everyone has the luxury of being a healthy 40-year-old with perfect veins. Some of us are just trying to survive without being called ‘noncompliant’ because we can’t feel a ‘thrill’ while juggling two jobs and a kid with autism.

And yeah, catheters are gross. But so is being dead. So shut up and stop judging people who are just trying to make it to tomorrow.

Brendan F. Cochran January 12, 2026

USA best. Fistulas are American engineering. We invented this stuff. Europe? They’re still using old-school grafts. China? They’re using catheters like it’s 1995. But here? We got sensors. We got exercise protocols. We got the best outcomes. Why? Because we don’t let bureaucracy slow us down.

And if you’re a foreigner complaining about equity? Get in line. We’ve got our own problems. People on dialysis in the US get better care than 90% of the world. Stop whining.

Also, catheters? Yeah they’re risky. But if you can’t afford to get a fistula? Maybe you shouldn’t be on dialysis at all. Just sayin’. Healthcare ain’t free, folks. You want the gold standard? Pay for it.

And stop letting liberals turn this into a political issue. It’s medicine. Not a protest.

jigisha Patel January 13, 2026

Statistical analysis reveals a significant flaw in the article’s conclusion: it conflates correlation with causation in asserting that fistula use directly reduces mortality. The data shows that patients who receive fistulas are statistically younger, healthier, and have fewer comorbidities at baseline. This is a classic selection bias. The mortality benefit is not caused by the access type-it is caused by patient selection.

Furthermore, the claim that catheters cost $15,000 more annually than fistulas ignores the cost of surgical intervention, preoperative imaging, and postoperative complications from failed maturation. When adjusted for total cost per life-year saved, grafts often demonstrate superior cost-effectiveness in elderly or diabetic populations.

Additionally, the ‘thrill’ is an unreliable clinical indicator. Studies show interobserver variability exceeds 35% in non-specialist populations. Relying on patient self-assessment for clot detection is not evidence-based-it’s anecdotal.

This article is emotionally compelling but clinically misleading. It promotes a dogma, not a strategy.

Jason Stafford January 13, 2026

They’re lying. Every single word. The ‘thrill’? It’s not blood flow. It’s a signal from the microchip they implanted during surgery. The whole ‘fistula first’ initiative? It’s a cover for the CDC’s biometric tracking program. They’re using your dialysis access to map your blood patterns, your heart rate, your sleep cycles-all to predict when you’ll die so they can sell your data to insurers.

And why do they say catheters are dangerous? Because they want you to believe you need a fistula so they can charge you $8,000 for the surgery, then $2,000 for the ‘maintenance’ visits, then $5,000 for the ultrasound. It’s a money machine.

The ‘bioengineered vessels’? They’re not made from donor tissue. They’re grown in labs using genetically modified human stem cells harvested from undocumented immigrants. That’s why they’re in Phase 3-because they’re still testing on the poor.

And the exercise? Ball squeezing? That’s just a way to get you to buy their branded resistance bands. I saw an ad for ‘DialysisFit™’ on YouTube last week. Same company that owns the Vasc-Alert.

You’re not being helped. You’re being harvested.

Mandy Kowitz January 14, 2026

Oh wow. A 20-page essay on dialysis access. Congrats, you just wrote the medical version of a Wikipedia page. Did you also include a flowchart? A PowerPoint? A 10-step checklist?

Here’s the real truth: most people don’t care. They’re too busy working, parenting, grieving, or just trying not to cry in the shower. And now you want them to check for a ‘thrill’ every day like it’s a daily meditation?

My aunt had a catheter for five years. She never felt a ‘thrill.’ She didn’t know what a graft was. She just showed up, got dialyzed, and went home. She’s alive. So maybe the ‘gold standard’ isn’t for everyone.

Stop making people feel guilty because they can’t be perfect patients. Sometimes ‘good enough’ is the only thing standing between them and death.

Also, I’m pretty sure the ‘Vasc-Alert’ is just a Fitbit with a stethoscope.

Justin Lowans January 15, 2026

This is one of the most thoughtful, meticulously researched, and humanely articulated summaries of dialysis access I have encountered in recent years. The integration of clinical data with patient narrative is both rare and profoundly effective.

I particularly appreciate the emphasis on equity-not as a buzzword, but as a measurable, actionable imperative. The fact that Black patients are 30% less likely to receive fistulas despite equivalent clinical need is not a statistical anomaly-it is a moral indictment.

Furthermore, the inclusion of emerging technologies-Vasc-Alert, bioengineered vessels, preoperative exercise-is not mere futurism; it is a roadmap toward justice. Innovation without equity is empty. This piece understands that.

As a clinician, I will be sharing this with every new patient and every resident on my team. It is not merely informative-it is transformative.

Thank you.

Cassie Tynan January 16, 2026

So let me get this straight: you’re telling me that if I squeeze a ball before surgery, I can magically turn my diabetic veins into superhero arteries? And if I don’t, I’m just lazy and doomed?

Meanwhile, my brother’s catheter got infected three times last year, and every time he went to the ER, they gave him antibiotics and sent him home. No one ever said, ‘Hey, maybe you should’ve done those wrist curls.’

And now I’m supposed to feel guilty because I didn’t ‘push for the best option’? What’s the best option when you’re 65, broke, and your insurance won’t cover vein mapping?

Don’t turn survival into a moral test. Some of us are just trying to get through the week without a fever. The rest of this is just noise.

John Ross January 18, 2026

Re: @6564 - You’re right. Not everyone gets the ‘ideal’ access. But that doesn’t mean we stop fighting for it. My patient, 78, diabetic, failed fistula, graft clotted twice-he got a third graft. Now he’s on it for 4 years. He checks his thrill. He calls us at the first sign of trouble. He’s alive. Not because he was lucky. Because he was educated. Because someone didn’t give up on him.

It’s not about perfection. It’s about persistence. And you don’t get persistence without access to information.

So yes-some people end up with catheters. But we shouldn’t accept that as the end of the conversation. We should treat it as the beginning of the fight.