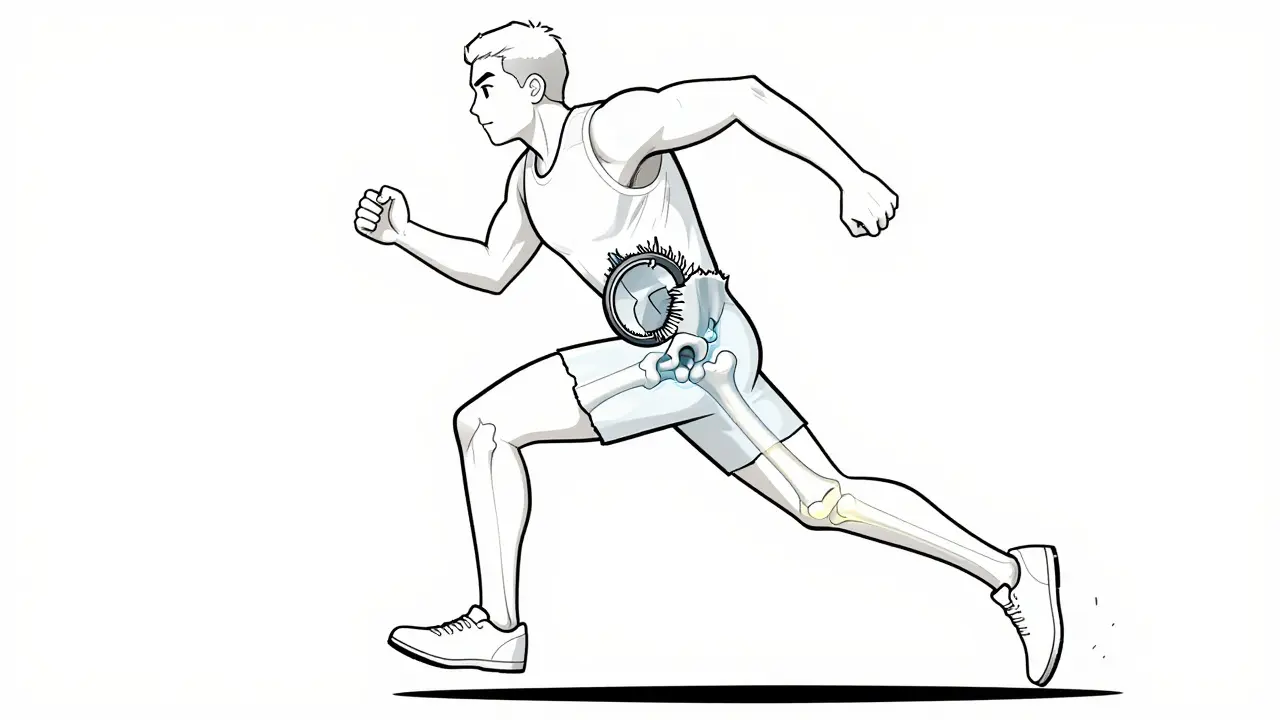

A hip labral tear isn’t just a minor injury-it’s a career-altering condition for athletes who rely on explosive hip movement. Whether you’re a soccer player cutting hard, a dancer spinning on pointe, or a runner with persistent groin pain, a torn labrum can sneak up on you. Unlike a sprained ankle or pulled hamstring, this injury doesn’t always show up on a standard X-ray. It hides in the deep socket of your hip, where cartilage that should protect the joint gets frayed or ripped. And if it’s not caught early, it can lead to early arthritis, chronic pain, or even the end of your sport.

What Exactly Is the Hip Labrum?

The labrum is a ring of tough, rubbery cartilage that wraps around the outer edge of the hip socket. Think of it like a seal on a mason jar-it keeps the ball of your femur snug inside the socket, stabilizes the joint, and absorbs shock during movement. When it tears, you don’t just feel pain. You might feel clicking, locking, or a deep ache in the groin or buttock that doesn’t go away with rest. For athletes, this isn’t just discomfort-it’s a red flag that something’s structurally wrong.

Most tears aren’t from a single traumatic event. They develop over time from repetitive motion. Sports like basketball, hockey, soccer, ballet, and gymnastics put extreme stress on the hip in flexion and rotation. Over hundreds of reps, the labrum wears down. In many cases, the real culprit is femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), where extra bone growth on the hip socket or femur causes the bones to grind against each other, slowly tearing the labrum. Studies show FAI is behind more than 70% of athletic labral tears.

How Do You Know It’s a Labral Tear?

It’s easy to mistake a labral tear for a groin strain or hip flexor issue. But there are telltale signs. If you’ve had persistent hip pain for more than 6 weeks, especially during activities that involve deep squatting, pivoting, or sitting for long periods, it’s worth getting checked. Doctors use two key physical tests: the FADIR test (flexion, adduction, internal rotation) and the FABER test (flexion, abduction, external rotation). When you’re asked to bring your knee toward your chest and rotate it inward, and it triggers sharp pain deep in the hip, that’s a strong indicator.

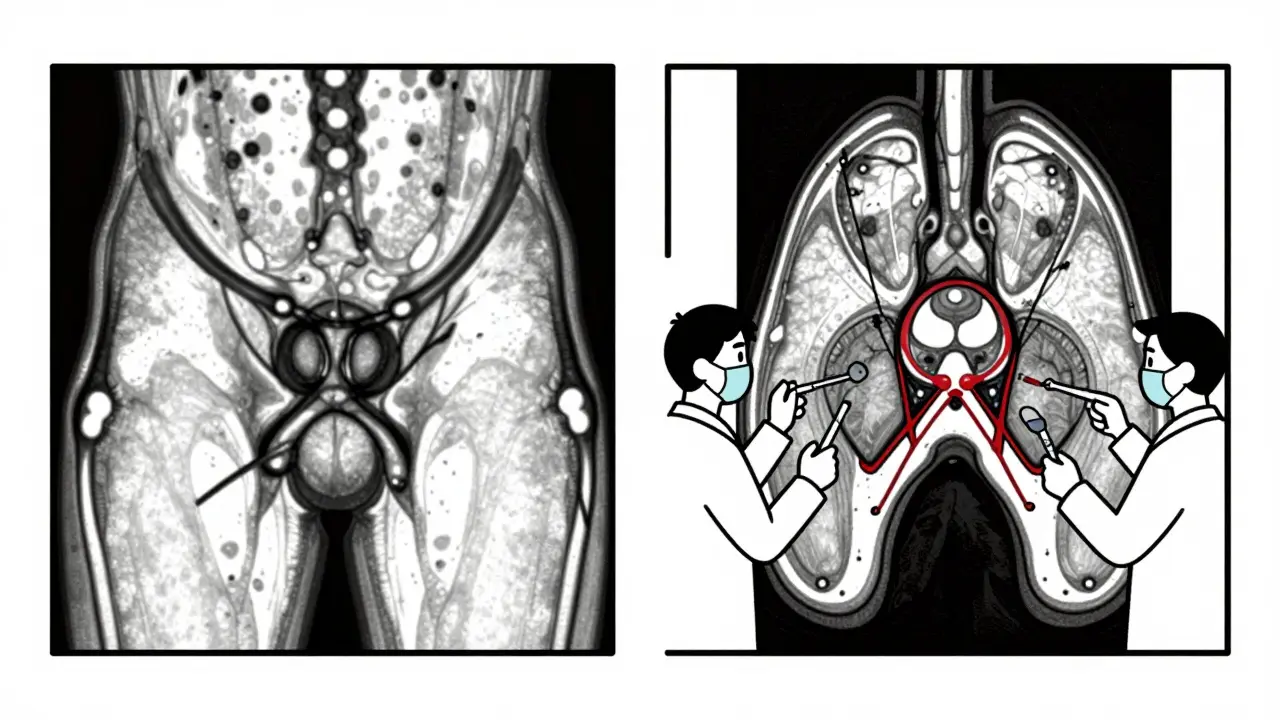

But physical exams alone aren’t enough. That’s where imaging comes in. Plain X-rays are the first step-not to see the tear, but to check for bone abnormalities like FAI, hip dysplasia, or arthritis. If those look suspicious, the next step is magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA). Unlike a regular MRI, MRA involves injecting contrast dye directly into the hip joint. This makes the labrum light up on the scan, revealing even small tears that standard imaging misses. MRA has a 90-95% accuracy rate, compared to just 35-60% for regular MRI.

Still, the gold standard is arthroscopy. It’s not just diagnostic-it’s therapeutic. During the procedure, a tiny camera is inserted into the hip joint, and the surgeon can see exactly what’s damaged. If the labrum is torn, they can either trim away the frayed edges (debridement) or stitch it back to the bone using suture anchors. This is the only way to be 100% sure what’s going on inside.

Conservative Treatment: When Surgery Isn’t the First Step

Not every labral tear needs surgery. For athletes with mild symptoms or those who aren’t competing at a high level, doctors often start with conservative care. That means 4-6 weeks of rest from high-impact activities, avoiding deep squats and twisting motions. Over-the-counter NSAIDs like ibuprofen or naproxen help reduce inflammation and pain.

Physical therapy is a big part of this phase-but it’s not one-size-fits-all. A good rehab program focuses on strengthening the glutes, core, and hip stabilizers, not just the quads. Many athletes get stuck in a cycle of doing generic core exercises that don’t address the real problem: poor hip control. Specialized sports PT clinics use motion analysis and real-time ultrasound to track how the hip moves during activity. One study from True Sports Physical Therapy found that 65% of athletes avoided surgery after a tailored rehab program.

Corticosteroid injections can also help. They don’t heal the tear, but they reduce swelling and pain enough to allow for better therapy. About 70-80% of patients get relief for 3-6 months. But if the pain comes back after the injection wears off, it’s a sign the tear is still there-and likely getting worse.

When Arthroscopy Becomes Necessary

If you’ve tried 3-6 months of conservative care and still can’t run, jump, or pivot without pain, surgery is the next step. Hip arthroscopy is minimally invasive, but it’s not simple. The hip joint is deep, surrounded by nerves and blood vessels, and the surgeon needs precise tools and experience. In fact, experts say it takes 50-100 supervised cases for a surgeon to become truly proficient.

There are two main surgical approaches: debridement and repair. Debridement means cutting away the damaged part of the labrum. It’s faster to recover from-most athletes return to sport in 3-4 months. But it’s not always the best choice. If the labrum is torn in a way that can be stitched back, repair is preferred. Suture anchors hold the labrum in place while it heals to the bone. Recovery takes longer-5-6 months-but it preserves the joint’s natural cushioning and reduces long-term arthritis risk.

Here’s the critical part: if you have hip dysplasia (a shallow socket), repairing the labrum alone is often a recipe for failure. Studies show 60-70% of these patients re-tear if the underlying bone issue isn’t fixed. That’s why top surgeons now combine labral repair with a procedure called periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) to reshape the socket. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons warns against isolated labral debridement in patients with FAI or dysplasia-it leads to 40% higher revision rates.

Recovery and Return to Sport

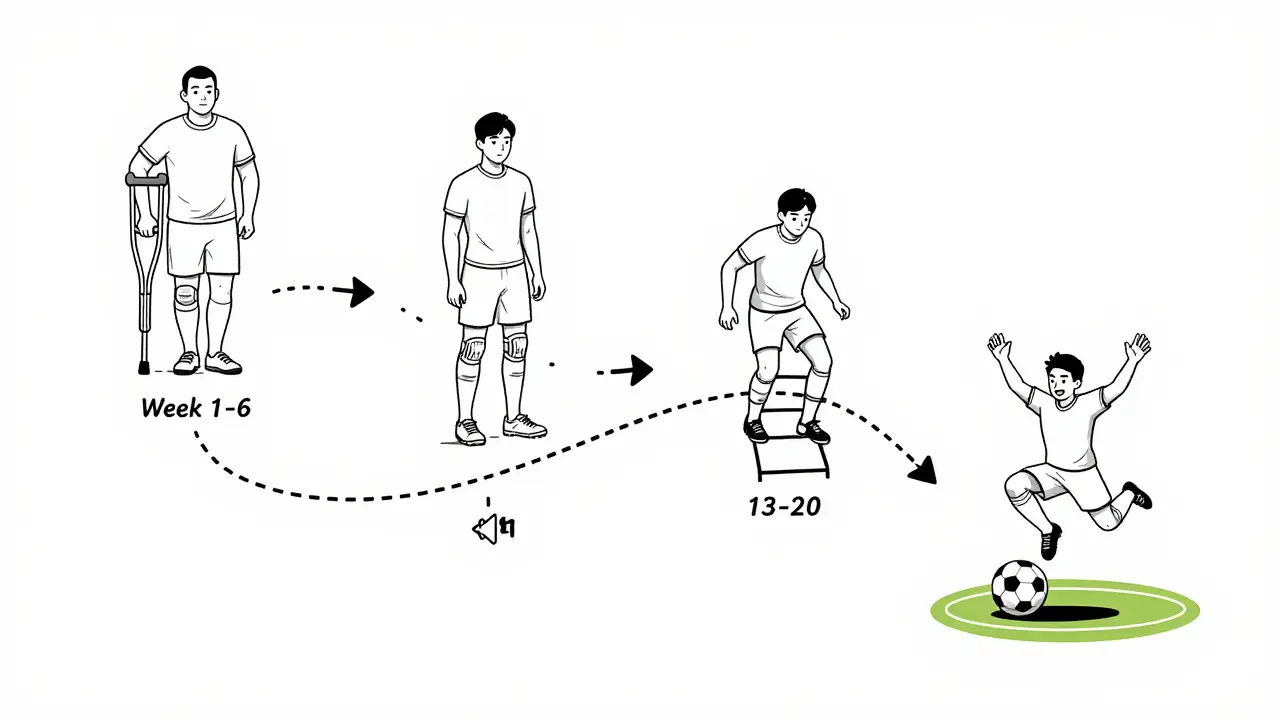

Recovery isn’t just about waiting for the pain to go away. It’s about rebuilding strength, control, and movement patterns. A structured rehab plan has four phases:

- Protection (weeks 1-6): No weight-bearing activities, limited hip motion, use of crutches if needed. Focus on reducing swelling and protecting the repair.

- Strengthening (weeks 7-12): Begin resistance training for glutes, hamstrings, and core. Progress to controlled hip rotations and balance drills.

- Sport-specific training (weeks 13-20): Start low-impact sport drills-agility ladders, light cutting, controlled jumps. Monitor for pain or clicking.

- Full return (weeks 21-26): Only return to full competition after hitting key benchmarks: 90% quadriceps strength symmetry and pain-free internal rotation to at least 30 degrees.

Professional athletes like NHL player Ryan Nugent-Hopkins took 5.5 months to return to elite hockey after labral repair. But amateur athletes often rush back. One Reddit user, a marathon runner, returned at 4.5 months and had no issues-another dancer had persistent clicking and needed revision surgery. The difference? Precision in rehab.

What Happens If You Don’t Treat It?

Ignoring a labral tear doesn’t make it go away. It makes it worse. The torn labrum loses its ability to cushion the joint. Bone starts rubbing against bone. A 15-year study published in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery found that untreated labral tears increase the risk of developing hip osteoarthritis by 4.5 times within a decade. That’s not a hypothetical risk-it’s a near-certainty for athletes who keep pushing through pain.

And it’s not just about the hip. When one joint hurts, the body compensates. You shift your weight, tighten your lower back, overuse your knee. That’s how one injury turns into three.

What’s New in 2025?

The field is evolving fast. In June 2023, the FDA approved the first bioabsorbable suture anchor designed specifically for labral repair. Unlike metal anchors, these dissolve over time, reducing long-term complications. Early data shows 89% success at two years-better than traditional anchors.

3D MRI is now recommended for complex cases, improving diagnostic accuracy to 97%. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections are being studied as a potential alternative to surgery. One trial showed 55% of patients avoided surgery after PRP, though results vary.

And the demand is rising. Over 150,000 hip arthroscopies were done in the U.S. in 2022-triple the number in 2010. The global market for hip arthroscopy tools is now $1.2 billion and growing. More athletes are getting diagnosed earlier because imaging and awareness have improved.

What Athletes Wish They Knew Sooner

Many athletes regret waiting too long. One common mistake: getting a standard MRI and being told everything looks fine-only to find out later the tear was missed. MRA is the only reliable imaging for labral tears. But it’s expensive-$1,200 to $1,800 in the U.S., often not covered by insurance. Athletes without access to sports medicine centers are more likely to be misdiagnosed.

Another surprise: not all pain is bad. After surgery, some mild discomfort during rehab is normal. But sharp, shooting pain, numbness in the thigh, or persistent clicking are red flags. These can signal nerve irritation, scar tissue, or a failed repair.

And don’t underestimate the psychological side. Many athletes feel defeated after a labral tear. They think their career is over. But the truth? 85-90% of athletes under 35 return to their pre-injury level of play. The key isn’t just surgery-it’s the right team: a surgeon who specializes in hips, a physical therapist who understands sports mechanics, and the patience to follow the plan.

Can a hip labral tear heal without surgery?

Yes, in some cases. Mild tears with minimal symptoms can improve with rest, physical therapy, and activity modification. About 65% of athletes avoid surgery with a targeted rehab program. But if the tear is large, associated with FAI or dysplasia, or causes persistent pain, surgery is usually needed to prevent long-term joint damage.

Is MRA better than MRI for diagnosing hip labral tears?

Yes, significantly. Standard MRI misses up to 30% of labral tears, especially partial-thickness ones. MRA uses contrast dye injected into the joint, making the labrum visible with 90-95% accuracy. It’s the recommended first-line imaging test after X-rays show possible structural issues.

How long does it take to return to sports after hip arthroscopy?

It depends on the procedure. After labral debridement, most athletes return in 3-4 months. After labral repair, recovery takes 5-6 months. Full return requires achieving 90% quadriceps strength symmetry and pain-free hip internal rotation. Rushing back increases the risk of re-tear.

Does hip dysplasia affect labral tear treatment?

Absolutely. If you have hip dysplasia-a shallow socket-repairing the labrum alone has a 60-70% failure rate. The underlying bone issue must be corrected surgically, often with a periacetabular osteotomy (PAO). Ignoring dysplasia leads to repeat tears and early arthritis.

What are the risks of hip arthroscopy?

Common risks include persistent pain (15-20%), nerve injury (1-2%), and heterotopic ossification (5-10%). Revision surgery is needed in 8-12% of cases within five years. The biggest risk isn’t the surgery itself-it’s having it done by a surgeon without specialized training. Outcomes improve dramatically at centers that perform over 50 hip arthroscopies per year.

What’s Next for You?

If you’re an athlete with ongoing hip pain, don’t wait for it to get worse. Start with X-rays to check for bone abnormalities. If those are normal but pain persists, push for an MRA-not a standard MRI. If a tear is found, find a surgeon who specializes in hip arthroscopy and understands the connection between labral tears and structural issues like FAI or dysplasia. And don’t skip rehab. Recovery isn’t just about healing the tissue-it’s about rebuilding how your body moves. The goal isn’t just to get back on the field. It’s to stay on it for years to come.

All Comments

Liz Tanner December 28, 2025

Finally, someone broke this down without the fluff. I had a labral tear in college and spent 8 months going in circles because every doctor just said 'rest and ice.' MRA was the game-changer - my first MRI said 'normal.' The dye made it obvious. Don't skip it.

Babe Addict December 29, 2025

Yeah but let’s be real - 70% of these tears are from FAI, which is basically a genetic glitch. You’re born with it. So why are we blaming athletes for ‘overuse’? It’s not training, it’s anatomy. And now we’re surgically correcting bone shape like it’s a software bug. Next they’ll be filing down our kneecaps.

Janice Holmes December 30, 2025

MY HIP JUST CLICKED WHEN I STOOD UP AND NOW I’M SURE I’M GOING TO NEED A HIP REPLACEMENT BY 30. I’M 24. I DID ONE PLYO CLASS. THIS IS A CONSPIRACY. THEY WANT US TO BUY EXPENSIVE MRA SCANS SO THEY CAN SELL US SUTURE ANCHORS. I SAW A YOUTUBE VIDEO WHERE A GUY SAID IT WAS JUST TIGHT FASCIA. I’M GOING TO ROLL ON A TENNIS BALL FOR 3 HOURS A DAY.

Gerald Tardif December 30, 2025

Been coaching track for 18 years. Saw a kid with a labral tear in 2017 - thought it was a groin pull. He kept running. By year two, he couldn’t squat. Got the MRA, got the repair, did every rep in rehab. Now he’s a D1 coach. The difference? He didn’t rush. He trusted the process. That’s the secret sauce. Not the surgery. The patience.

Alex Lopez December 31, 2025

It’s fascinating how medicine has evolved from ‘take NSAIDs and pray’ to precision biomechanical intervention. That bioabsorbable anchor? Brilliant. No more metal artifacts on future MRIs, no long-term migration risk. Though I must say, the $1,800 MRA price tag is unconscionable in a country that bills $12,000 for a broken toe. We’ve commodified pain.

Olivia Goolsby December 31, 2025

And who benefits? The ortho-industrial complex. The FDA approves a new anchor - boom, $500 markup. Insurance won’t cover MRA unless you’ve already wasted 6 months on PT and 3 different doctors. And don’t get me started on the ‘85% return rate’ - that’s only for athletes who can afford $20K in out-of-pocket costs. Meanwhile, the kid working two jobs and playing pickup basketball? He’s told to ‘just stretch.’ They don’t want you healed - they want you compliant.

Raushan Richardson January 1, 2026

Y’all are overthinking this. I tore mine in a yoga class. No FAI, no dysplasia - just bad form and too much ego. Did 8 weeks of PT, avoided squats, did glute bridges like my life depended on it. Back to dancing in 4 months. No surgery. No drama. Just consistency. If your PT is just having you do planks, find a new one. The hip isn’t your abs.

Liz MENDOZA January 2, 2026

To the person who said they’re going to roll on a tennis ball - I see you. I’ve been there. That clicking? It’s terrifying. But please, don’t give up on care. Find a sports PT who does movement screens. I did. And it didn’t fix the tear - but it fixed how my body compensated. I still have the tear. But I don’t feel it. That’s the win.

Monika Naumann January 3, 2026

In India, we do not have such expensive imaging or surgeries. We have Ayurveda, yoga, and patience. Our ancestors did not have MRA, yet they moved with grace. Modern medicine is obsessed with cutting and replacing. Perhaps the problem is not the hip - but the arrogance of intervention.

Satyakki Bhattacharjee January 4, 2026

Life is pain. Every man has pain. The hip is just one part. If you cannot endure a little ache, how will you endure life? I have no money for MRI. I have no time for PT. I run anyway. Pain is a teacher. It tells you to slow down. Not to get a machine to fix you. You are not a machine.

Jane Lucas January 5, 2026

i had this and just kept running til i couldnt walk. went to er they said ‘maybe see a doc?’ turned out i had a tear and faI. mra cost me 1500 out of pocket. surgery was worth it. now i can squat again. dont be like me. get the mra.

Robyn Hays January 6, 2026

What’s wild is how much this mirrors ACL recovery - same structure, same timeline, same psychological toll. You don’t just heal tissue, you rebuild identity. I used to be the girl who could spin 12 pirouettes. Now I’m the girl who does slow glute bridges and cries when her hip clicks. But I’m back. Not the same. Better.