When a brand-name drug’s patent expires, the first generic version usually hits the market at about 15% to 20% of the original price. That’s a big drop-but it’s only the beginning. The real savings come when a second and then a third generic manufacturer enters the race. These later entrants don’t just lower prices a little-they trigger a chain reaction that can slash costs by more than half within months.

Why the second generic changes everything

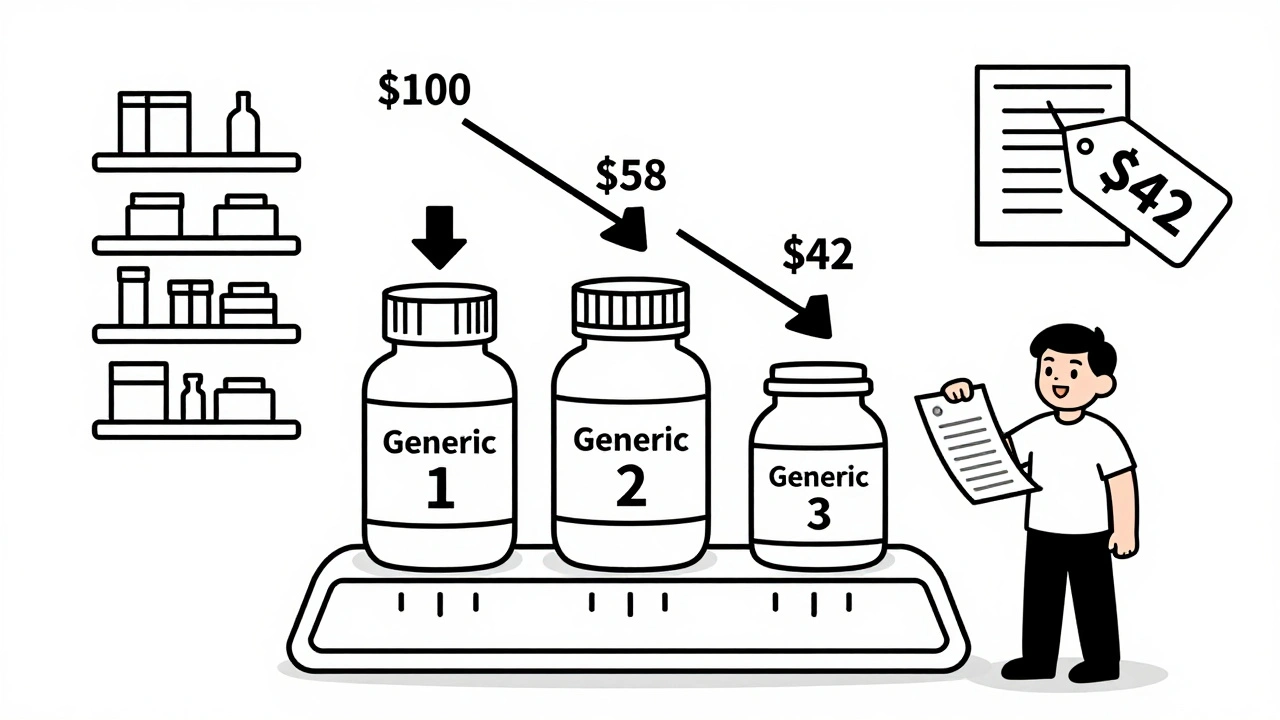

The first generic drug maker doesn’t have much pressure to cut prices. They’re the only option, so they can hold onto a decent margin. But as soon as a second company gets FDA approval and starts selling the same drug, everything shifts. Suddenly, there are two suppliers. Pharmacies and insurers can play them against each other. The first company can’t charge the same price anymore-it’ll lose business. So they drop their price. The second company, eager to win market share, drops theirs even lower. The result? Prices often fall to about 58% of what the brand used to cost. This isn’t theory. The FDA analyzed data from 2018 to 2020 and found that when a second generic entered the market, prices dropped by an average of 36% compared to the first generic alone. That’s not a small tweak. That’s a massive shift in what patients pay out of pocket.The third generic hits the accelerator

Add a third generic manufacturer, and the pressure multiplies. Now there are three companies fighting for the same customers. Each one needs to undercut the others just to stay in the game. This isn’t just about volume-it’s about survival. In markets with three or more generic makers, prices typically fall to just 42% of the original brand price. The data shows this pattern clearly: the first generic cuts prices to about 87% of the brand’s cost. The second brings it down to 58%. The third? It plummets to 42%. That’s a 50% drop from the second to the third entry alone. For a drug that used to cost $100 a month, that means the price now sits around $42. For patients on chronic medications-like blood pressure pills, diabetes drugs, or cholesterol meds-that’s hundreds of dollars saved every year.What happens when competition stalls

But here’s the catch: not all generic markets get to three competitors. Nearly half of all generic drug markets in the U.S. are stuck with just two manufacturers-a duopoly. And in those cases, prices don’t keep falling. They stabilize. Sometimes, they even rise. A 2017 study from the University of Florida found that when competition dropped from three manufacturers to two, prices jumped by 100% to 300% in some cases. Why? Because with only two players, they can quietly coordinate pricing without fear of losing customers to a third option. It’s not collusion-it’s just the natural result of too little competition. That’s why the entry of the third generic isn’t just helpful-it’s critical. It breaks the duopoly. It forces transparency. It turns a market that could become a price-fixing club into one where patients win.

Who benefits-and who doesn’t

Patients are the biggest winners. Lower drug prices mean fewer people skip doses or stop taking their meds because they can’t afford them. The FDA estimates that the 2,400 new generic drugs approved between 2018 and 2020 saved consumers $265 billion. That’s not a guess. That’s based on actual sales data and price tracking. Insurers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) also benefit. With more generic options, they have more leverage to negotiate better discounts. Evernorth, one of the largest PBMs, found that when five or more generics are available for a drug, they can secure discounts that are nearly double what they get with just one or two suppliers. But not everyone wins. Generic manufacturers themselves face pressure. As prices fall, profit margins shrink. Some small companies can’t afford the costs of FDA approval, production, or distribution. That’s why the number of independent generic makers has dropped over the past decade. Teva bought Allergan’s generics division. Viatris formed from the merger of Mylan and Upjohn. Now, just a handful of big players control most of the market. And then there are the middlemen: the three major wholesalers-McKesson, AmerisourceBergen, and Cardinal Health-control 85% of the distribution. PBMs handle 80% of prescriptions. They’re not in the business of lowering drug prices. They’re in the business of maximizing their own margins. So even when generics get cheaper, patients don’t always see the full savings.What’s blocking more competition?

You’d think the more generic drugs approved, the better. But the system has built-in roadblocks. One major issue is “pay for delay.” That’s when a brand-name company pays a generic manufacturer to stay out of the market. It’s legal in some cases, and it’s devastating. The Blue Cross Blue Shield Association estimates these deals cost patients $3 billion a year in higher out-of-pocket costs. They also cost the system $12 billion annually in total. Another tactic is “patent thicketing.” Brand companies file dozens, sometimes over 70, overlapping patents on a single drug. Even after the main patent expires, these secondary patents can block generics for years. One drug had 75 patents that extended its monopoly from 2016 to 2034. That’s 18 extra years of high prices. The FDA has tools to fight back. The CREATES Act, passed in 2022, stops brand companies from refusing to supply samples to generic makers-something they used to do to delay approvals. And the GDUFA III program, running from 2023 to 2027, is designed to speed up reviews for complex generics, which are harder to copy and often have fewer competitors.

What’s next for generic pricing

The trend is clear: more competitors = lower prices. But the number of new generic entrants is slowing. Consolidation among manufacturers, rising production costs, and regulatory delays are making it harder for smaller companies to join the race. Still, the data doesn’t lie. Every additional generic competitor drives prices down. Markets with 10 or more generic makers see price reductions of 70% to 80% compared to the original brand. That’s the gold standard. The challenge now is ensuring more companies can enter. Policy changes-like banning pay-for-delay deals, cracking down on patent abuse, and supporting small generic manufacturers-could unlock billions more in savings. The Congressional Budget Office warns that without action, Medicare could lose $25 billion a year by 2030 because generic competition isn’t keeping pace.What patients can do

You don’t need to wait for lawmakers to act. If you’re on a generic drug, ask your pharmacist: “Are there other generic brands available?” Sometimes, switching to a different manufacturer can cut your cost in half. Ask your doctor to prescribe by generic name, not brand. And if your insurance denies a cheaper generic, appeal it. Many times, the cheaper version is already approved and just not listed as preferred. The system works best when patients demand competition. The second and third generics aren’t just alternatives-they’re the reason drug prices fall. Without them, you’re paying more than you should.Why do generic drug prices keep dropping after the first one enters the market?

The first generic often charges a price close to the brand because it has no competition. When a second company enters, they undercut the first to win business. The first company then lowers its price to stay competitive. A third entrant pushes prices even lower, often cutting them to less than half the original brand price. More competitors mean more pressure to reduce prices.

How much can I save with a third generic drug?

If a brand drug cost $100 per month, the first generic might cost $15. The second could bring it down to $60, and the third might drop it to $42. That’s a 58% savings compared to the first generic alone. For chronic medications, that adds up to hundreds of dollars saved per year.

Why aren’t there more generic versions of some drugs?

Some drugs are hard to copy-like inhalers or complex injectables. Others face legal barriers, like brand companies using patents to block competitors or paying generics to delay entry. Manufacturing costs and low profit margins also discourage small companies from entering the market. As a result, many drugs only have one or two generics, even years after patent expiry.

Does switching between generic brands affect how well the drug works?

No. All generic drugs must meet the same FDA standards as the brand name: same active ingredient, same dosage, same effectiveness and safety. The only differences are in inactive ingredients, like fillers or coatings, which don’t affect how the drug works. Many patients switch generics without noticing any change.

Can my pharmacy refuse to give me a cheaper generic?

Pharmacies typically stock the cheapest option to minimize costs, especially under insurance contracts. But if your insurance doesn’t cover a cheaper generic, or if your doctor specified a particular brand, you may be limited. Ask your pharmacist if other generics are available and if you can request a switch. You can also ask your doctor to write "dispense as written" only if you need a specific version.

All Comments

Scott Butler December 11, 2025

These generic drug companies are just exploiting loopholes. We built the American pharmaceutical industry from the ground up, and now some foreign manufacturer gets to undercut us with cheap labor and zero R&D investment? It’s not competition-it’s economic betrayal. The FDA should be protecting American jobs, not handing out approvals like candy.

Emma Sbarge December 12, 2025

I’ve been on a generic blood pressure med for five years. Switched from the first generic to the third one last year-my copay dropped from $45 to $12. No difference in how I feel. If your doctor says they’re all the same, they’re right. Stop overpaying because you’re scared of the unknown.

Lauren Scrima December 13, 2025

Oh, so now we’re supposed to be thrilled that corporations are finally competing… after they’ve already gouged us for years? 🤦♀️ The fact that we need THREE generic manufacturers just to get prices down to 42% of the brand is a national disgrace. And don’t even get me started on the PBMs pocketing the difference.

Casey Mellish December 14, 2025

As an Aussie, I’ve seen this play out here too-Medicare’s generic pricing system is way more aggressive. We get five or six generics for the same drug within months of patent expiry. Prices crash, patients win. The U.S. system is broken because it prioritizes corporate profits over public health. It’s not rocket science: more competitors = lower prices. Why is this even controversial?

Yatendra S December 15, 2025

Life is a paradox, no? We seek freedom, yet we are chained by patents. The third generic is not just a drug-it is the echo of democracy in a marketplace that forgot its soul. 💭💊 When the market becomes a monastery of monopolies, who prays for the sick? The answer, my friend, lies not in pills… but in power.

Himmat Singh December 15, 2025

It is imperative to note that the empirical data presented herein, while statistically significant, fails to account for the macroeconomic implications of market saturation in the pharmaceutical supply chain. The reduction in per-unit pricing may inadvertently disincentivize innovation in biosimilar development, thereby compromising long-term therapeutic advancement. One must consider the systemic trade-offs.

kevin moranga December 16, 2025

Hey, I just want to say-this is actually one of the most hopeful things I’ve read in a while. Seriously. I’ve got a kid with asthma, and we were paying $90 a month for the inhaler. Found a third-party generic last month-$18. Same exact device, same results. It’s not magic, it’s just competition. And if we can make this work for inhalers, we can make it work for everything. Keep pushing, keep asking your pharmacist, keep fighting. You’ve got this.

Alvin Montanez December 17, 2025

Let’s be real: nobody cares about the third generic unless they’re on Medicare or on a fixed income. The rest of us? We just take whatever our insurance gives us. And guess what? Most of the time, it’s the most expensive version because the PBM got a kickback from the manufacturer. So yeah, sure-more generics sound great on paper. But until we take the profit motive out of pharmacy benefits, this is all just performative activism with a spreadsheet.

Lara Tobin December 18, 2025

I cried when I switched to the third generic for my diabetes med. Not because it worked better-but because I could finally breathe again. No more choosing between insulin and groceries. Thank you to whoever wrote this. It’s not just data-it’s survival.

Jamie Clark December 18, 2025

You’re all missing the point. The real villain isn’t the brand name company or the PBM-it’s the FDA’s slow approval process. They’re the gatekeepers. If they approved generics faster, we wouldn’t be stuck with duopolies for years. The system isn’t broken because of greed-it’s broken because of bureaucracy. And bureaucracy is just government failing to do its job. Again.