When you walk into a pharmacy in the U.S. and see a $5 copay for your generic blood pressure pill, it’s easy to think you’re getting a deal. But here’s the twist: generic drugs in the United States are actually cheaper than in most other wealthy countries - even as brand-name drugs cost two to four times more than anywhere else. This isn’t a mistake. It’s the result of how the U.S. healthcare system works - and why your out-of-pocket costs for generics are lower, while your overall spending on medicine is still the highest in the world.

Why U.S. Generic Drugs Are So Cheap

The U.S. market for generic drugs is unlike any other. About 90% of all prescriptions filled in the country are for generics. That’s far higher than in countries like Germany (55%) or the UK (70%). Why? Because the system pushes doctors and pharmacists toward cheaper options. Insurers, Medicare, and Medicaid all have strong incentives to use generics. And when multiple companies make the same drug, prices crash.

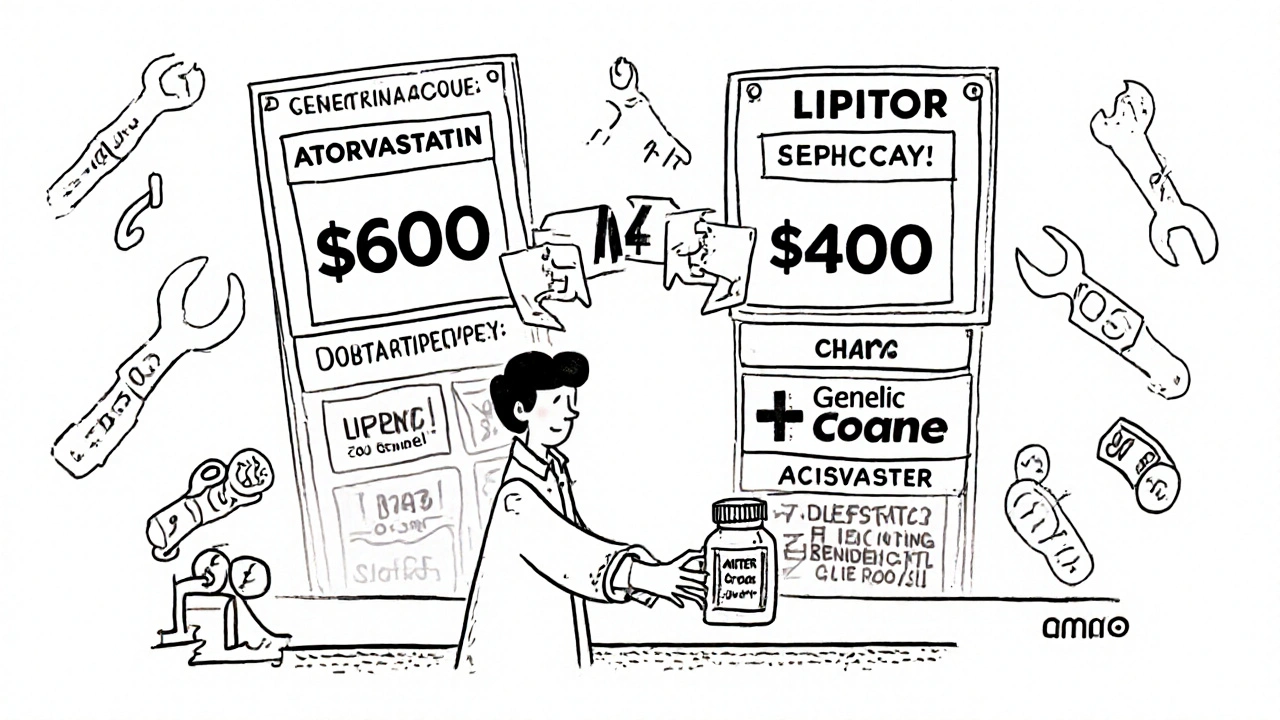

Here’s how it works: When a brand-name drug’s patent expires, the first generic maker might sell it for 30-40% of the original price. Add a second competitor? It drops to 20-25%. By the time three or four companies are making it, the price falls to just 15-20% of the brand. That’s not speculation - it’s based on FDA data from 2019 and confirmed by IQVIA’s sales records. For example, the generic version of the cholesterol drug atorvastatin (Lipitor) now costs less than $4 a month in many U.S. pharmacies. In Canada, it’s around $12. In France, it’s $18.

That’s why the average U.S. generic copay is $6.16, according to the 2023 U.S. Generic and Biosimilar Medicines Savings Report. In comparison, the average brand-name copay is $56.12 - nearly nine times higher. And 93% of generic prescriptions in the U.S. cost under $20. Only 59% of brand-name prescriptions do.

But Brand-Name Drugs Are Wildly Expensive

Here’s where things flip. While generics are cheap, brand-name drugs in the U.S. are the most expensive in the world. According to a 2022 RAND Corporation study commissioned by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. brand-name drug prices are 308% higher than in 33 other OECD countries. For originator drugs - the very first version made by the original company - prices are 422% higher.

Take Jardiance, a diabetes drug. Medicare negotiated a price of $204 for a 30-day supply. In Japan, the same drug costs $52. In Australia, it’s $48. Stelara, used for psoriasis and Crohn’s disease, costs $4,490 in the U.S. under Medicare. In Germany, it’s $2,822. In France, it’s $2,100. These aren’t outliers - they’re typical.

The reason? The U.S. doesn’t regulate drug prices. Other countries do. Canada, the UK, Germany, France, and Japan all have government agencies that negotiate prices or set price caps. The U.S. doesn’t - until recently. The Inflation Reduction Act let Medicare negotiate prices for 10 drugs in 2024, but even those negotiated prices are still higher than what other countries pay. In fact, of the first 10 negotiated drugs, only one (Stelara in Germany) had a lower price in another country than the U.S. Medicare rate.

The Gross vs. Net Price Confusion

You might hear that U.S. drug prices are 2.78 times higher than other countries. That’s true - but it’s misleading. That number is based on list prices, the sticker price before discounts. In reality, the U.S. system uses massive rebates and discounts, especially in public programs like Medicare Part D and Medicaid. A 2024 study from the University of Chicago found that after all these discounts, the U.S. actually pays 18% less than peer countries for public-sector prescriptions.

Think of it like this: A car dealership lists a vehicle at $40,000. But if you’re a big buyer - say, a rental company - they give you a $15,000 discount. The list price is still $40,000. But the real price you pay? $25,000. That’s what’s happening with U.S. drug prices. The list price is sky-high. But the net price - what insurers and government programs actually pay - is often lower than in countries that don’t use rebates.

That’s why experts like Dr. Dana Goldman from USC say, “Americans do quite well in the generic market.” He’s right. But only for generics. For brand-name drugs, the U.S. is still the most expensive place on Earth.

Why Other Countries Pay Less

France and Japan consistently have the lowest drug prices in the OECD. Why? Because their governments set prices before a drug even hits the market. They look at how effective the drug is, how much it costs to make, and what other countries pay. Then they set a ceiling. If the company doesn’t like it, they don’t sell there.

In Germany, prices are negotiated between drugmakers and sickness funds (nonprofit insurers). In the UK, the NHS uses a value-based pricing system. If a drug doesn’t offer enough benefit for its cost, it’s not approved.

The U.S. doesn’t have any of that. Drugmakers set their own prices. And because Americans pay out of pocket more than people in other countries - and because insurers have less leverage - prices stay high. Even when Medicare negotiates, it’s still paying more than other nations because it’s negotiating against a system built on inflated list prices.

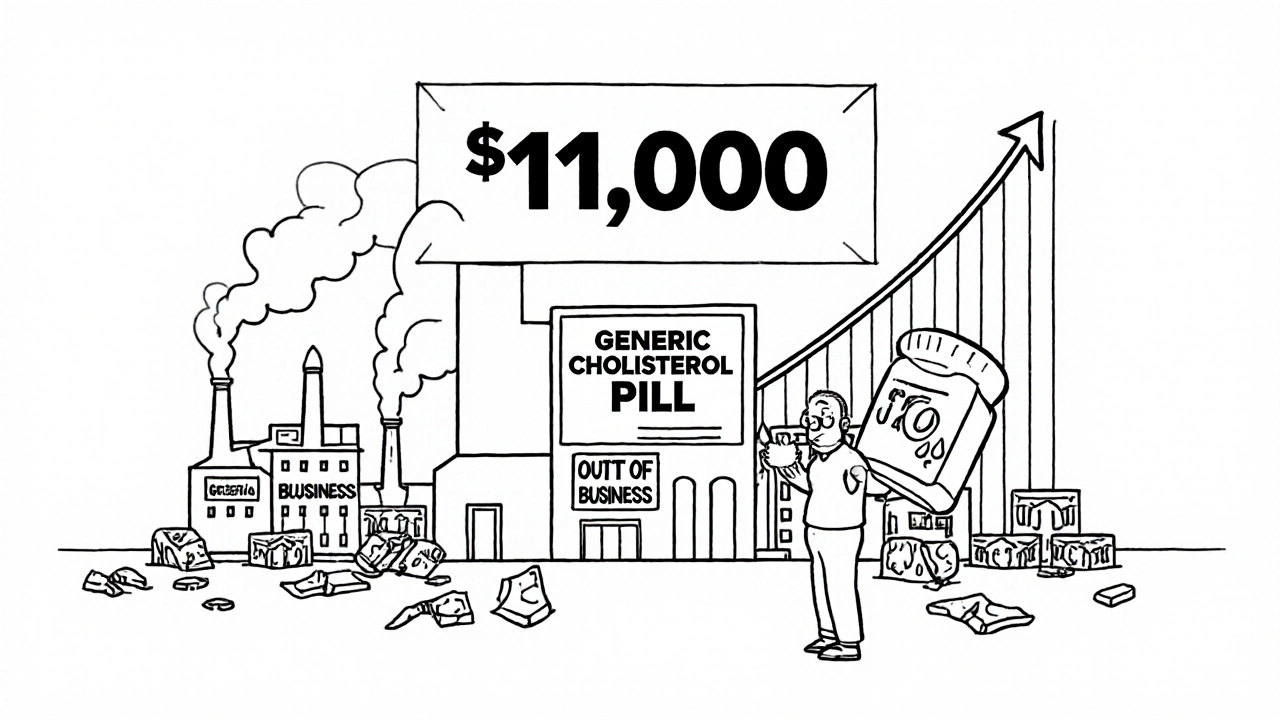

What Happens When Generic Competition Fails

It’s not always smooth sailing. Sometimes, a generic drug hits the market, and then… nothing. No other company enters. Why? Because the profit margin is too thin. One manufacturer might make $0.02 per pill. If they can’t sell enough, they quit. And then you’re back to a monopoly.

The FDA has documented cases where a generic drug disappeared after one manufacturer left the market - and then the price jumped 500% overnight. That’s how you get a $1,000 pill for a drug that used to cost $10. These are rare, but they happen. And they hurt patients who depend on the drug.

That’s why the FDA’s approval of 773 generic drugs in 2023 could save $13.5 billion. More competition = lower prices. But only if enough companies are willing to play.

Who Pays the Real Cost?

Most Americans never see the full price of their drugs. Insurance covers it. Medicare covers it. Medicaid covers it. But who pays for those coverages? You do - through premiums, taxes, and higher prices on everything else.

High brand-name drug prices fund global innovation. The U.S. pays more so drug companies can afford to develop new treatments. That’s the argument. But critics say other countries are free-riding - getting the benefits of U.S.-funded research without paying their fair share.

That’s why some researchers at the University of Chicago suggest the U.S. should push for trade deals that make other countries pay more. It’s a controversial idea. But it’s gaining traction.

The Bottom Line

If you take mostly generic drugs, you’re probably paying less than people in most other developed countries. That’s a win. But if you need a brand-name drug - especially for chronic conditions like cancer, MS, or rheumatoid arthritis - you’re paying more than anyone else on the planet.

The U.S. system isn’t broken. It’s designed this way. Generics are cheap because competition is fierce. Brand-name drugs are expensive because there’s no price control. And while the net cost to the system might be lower than the list price suggests, the human cost - in stress, skipped doses, and financial strain - is real.

For now, the best advice is simple: Ask your doctor if a generic is available. Check your pharmacy’s discount program. Use GoodRx. And know this: Your $5 generic isn’t a fluke. It’s the result of a system that works - for some drugs, for some people. But the rest of the system? It’s still broken.

Why are generic drugs cheaper in the U.S. than in other countries?

The U.S. has a highly competitive generic drug market with 90% of prescriptions filled as generics. When multiple manufacturers produce the same drug, prices drop sharply - often to 15-20% of the brand-name price. Other countries have fewer generic competitors and government price controls that don’t always drive prices down as aggressively.

Are U.S. brand-name drug prices the highest in the world?

Yes. According to the RAND Corporation and the Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. brand-name drug prices are about 308% higher than in other OECD countries. For originator drugs, the gap is even wider - up to 422% higher. Countries like France, Japan, and Australia have strict price controls that keep costs low.

Does Medicare negotiate lower drug prices than other countries?

No. Even after Medicare negotiated prices for 10 drugs in 2024, those prices were still higher than what other countries pay. For example, Medicare’s price for Jardiance was $204 - more than three times what Japan and Australia pay. Only one of the 10 negotiated drugs had a lower price in another country.

Why do some generic drugs suddenly become very expensive?

When only one company makes a generic drug, it can raise prices without competition. If other manufacturers exit the market due to low profit margins, the remaining company becomes a monopoly. The FDA has documented cases where prices jumped 500% after competitors left. This is rare but dangerous for patients who rely on those drugs.

Can I save money on prescriptions in the U.S.?

Yes. Always ask for a generic version. Use tools like GoodRx or SingleCare to compare prices at local pharmacies. Many pharmacies offer $4 or $10 generic programs for common medications. Medicare Part D also has a cap on out-of-pocket spending starting in 2025, which will help people on high-cost drugs.

Is the U.S. paying too much for drugs overall?

Yes - but not because of generics. The U.S. spends far more on healthcare because of high brand-name drug prices, not because generics are expensive. In fact, generics save the U.S. system an estimated $300 billion annually. The problem is that 10% of prescriptions (brand-name drugs) account for nearly 80% of total drug spending.

All Comments

Erin Nemo December 1, 2025

My $5 generic blood pressure pill is literally the only thing keeping me alive and sane. I don’t care how the system works as long as it keeps working for me. 🙏

ariel nicholas December 1, 2025

Let’s be real-America doesn’t need price controls. We’re the land of the free, and if you can’t afford your meds, maybe you shouldn’t have been born in the 21st century! The market decides-and the market says: ‘You want it? Pay for it.’

Other countries? They’re just welfare parasites who want our innovation for free. We fund the world’s drugs-and they get mad when we don’t give them a discount? Get. Out.

And don’t even get me started on ‘net prices’-that’s just corporate spin wrapped in a lab coat. The sticker price is the truth. The rest is socialism in a pill bottle.

Rachel Stanton December 1, 2025

It’s critical to distinguish between list price and net price-it’s not just semantics, it’s systemic. The U.S. pays higher list prices, but because of rebate structures, payer-level spending is often lower than in single-payer systems. That’s not a loophole-it’s a feature of a complex, multi-payer ecosystem.

What’s often missed is that generics thrive here because of scale, regulatory clarity, and FDA’s ANDA pathway. Other countries have slower approval timelines, which suppresses competition. And yes, the 90% generic utilization rate is a public health win.

But we must acknowledge the fragility: when a market has only one manufacturer for a low-margin generic, it’s a single point of failure. We need policy interventions that incentivize multiple producers, not just rely on market forces.

Also-thank you for mentioning GoodRx. That tool has saved my patients thousands. We need more transparency tools like that.

Amber-Lynn Quinata December 2, 2025

Ugh. I can’t believe people are still acting like this is normal. 😒 You think your $5 pill is a gift? It’s a trap. You’re being manipulated. The system is rigged to make you think you’re saving money while the real cost is buried in your premiums, your taxes, your kid’s college fund, and your mental health.

And don’t even get me started on how pharma companies use ‘innovation’ as an excuse to charge $100,000 for a drug that costs $2 to make. 💸

Someone’s got to say it: We’re being robbed. And we’re too numb to notice.

Lauryn Smith December 3, 2025

I just want to say thank you to the person who wrote this. It’s so clear and helpful. I’ve been confused about why my insulin is $300 but my metformin is $4. Now I get it. Generics are a miracle. Brand names? Not so much.

If you’re on meds, always ask your pharmacist about generics. And if they say there isn’t one-ask again. Sometimes there is.

Bonnie Youn December 4, 2025

STOP acting like this is complicated. It’s not. The U.S. is the only country where drug companies can charge whatever they want and no one stops them. That’s not capitalism-that’s corporate feudalism.

Generics are cheap because there’s competition. Brand names are expensive because there’s a monopoly. Simple. Fix it. Pass laws. End the greed. We’ve got the power. Use it.

And yes-I’m mad. And you should be too.

Edward Hyde December 6, 2025

So let me get this straight-America pays more for brand names, but we get cheaper generics because we’re basically a drug cartel with a side of Medicaid? Sounds like a middle finger to the rest of the world wrapped in a prescription bottle.

Meanwhile, my cousin in Poland pays $1 for the same generic. And he still thinks we’re rich because we have Walmart. Bro.

Also, why is no one talking about how the FDA approves 700+ generics a year but 90% of them are made in India and China? We’re outsourcing our health care and calling it a win? 😂

Charlotte Collins December 7, 2025

The entire narrative here is dangerously reductive. You celebrate the $5 generic while ignoring the fact that 20% of Americans skip doses because they can’t afford the co-pay-even for generics. You cite net prices while ignoring that rebates flow to PBMs, not patients. You call it a ‘system that works’-but it works for insurers, not people.

And let’s not pretend the Inflation Reduction Act is a victory. Ten drugs? Out of 10,000? That’s not reform. That’s PR.

This isn’t a pricing issue. It’s a moral failure dressed up in econometrics.

Margaret Stearns December 7, 2025

Just wanted to say I really appreciate this breakdown. I’ve been on lisinopril for 12 years and never knew why it was so cheap here. Also-thank you for mentioning GoodRx. I use it every month. I had no idea pharmacies had different prices. 🙏

One typo: ‘medicaid’ should be capitalized. But otherwise, perfect.

amit kuamr December 7, 2025

USA is the land of capitalism and innovation. Other countries are just copying. Why should they pay less when they do not invest in R&D? The real problem is not America-it is the free riders who take our science and sell it cheap

Also generics are not medicine. They are copies. Real medicine is expensive because it takes years and billions. You want cheap? Go to India. But do not complain when your cancer drug does not work

Erin Nemo December 9, 2025

@amit kuamr-your point about India is valid, but the generics here are FDA-approved. They’re not knockoffs. And yes, we fund innovation-but we also pay 5x more than everyone else for the same drugs. That’s not innovation. That’s exploitation.

And if your cancer drug doesn’t work, it’s probably because you’re getting a counterfeit from a shady site. Not because U.S. generics are bad.