Most people think obesity is just about eating too much and moving too little. But that’s not the full story. Behind the scale, there’s a biological system that’s been rewired-where hunger signals won’t turn off, fullness doesn’t register, and your body fights to hold onto every extra calorie. This isn’t laziness. It’s obesity pathophysiology: a complex breakdown in how your brain and body regulate energy.

The Brain’s Hunger Control Center

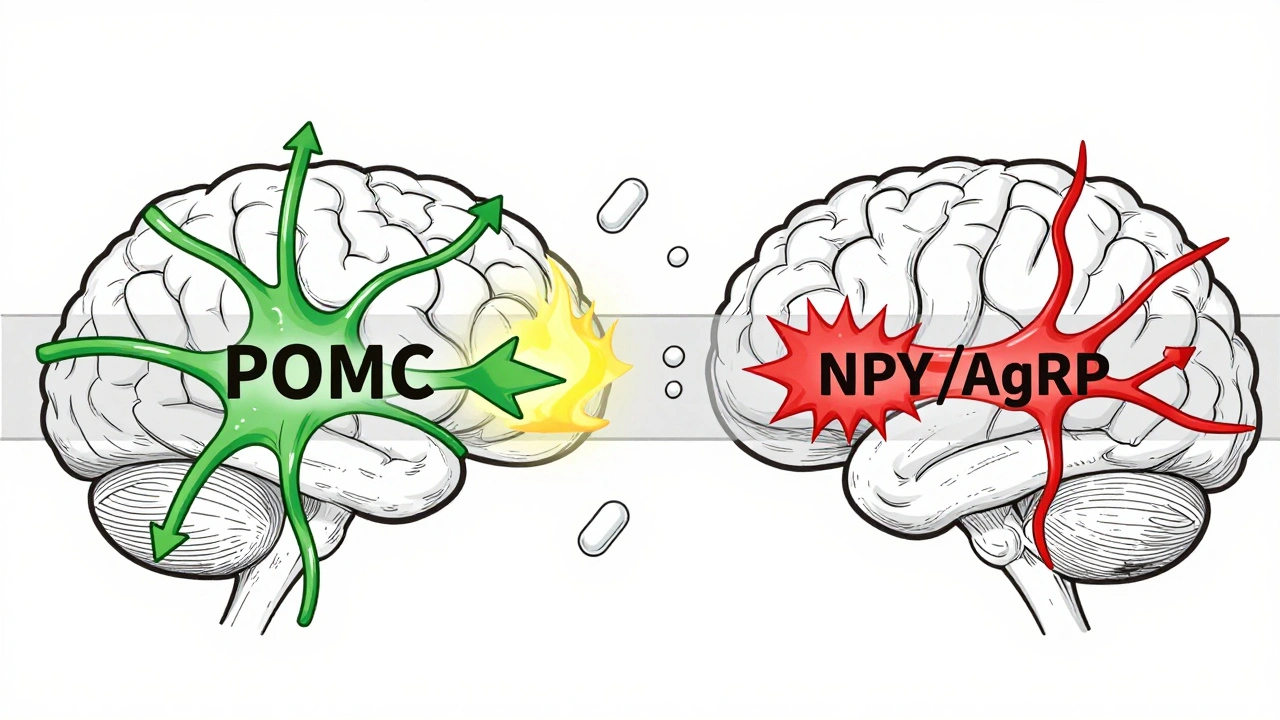

At the heart of this system is a tiny region in your brain called the arcuate nucleus, part of the hypothalamus. Think of it as the control tower for your appetite. It has two opposing teams of neurons working constantly to keep your weight stable. One team, made up of POMC neurons, tells you to stop eating. When activated, they release alpha-MSH, a chemical that triggers fullness. In experiments, turning on these neurons cuts food intake by 25% to 40%. The other team, NPY and AgRP neurons, screams for more food. When these fire, they can make a mouse eat 300% to 500% more in minutes. In humans, this system is just as powerful. These neurons don’t work alone. They listen to signals from your fat, gut, and pancreas. Leptin, the hormone your fat cells make, is supposed to tell your brain: “We’ve got enough stored.” In lean people, leptin levels sit between 5 and 15 ng/mL. In obesity, those numbers jump to 30-60 ng/mL. But here’s the catch: your brain stops listening. This isn’t a lack of leptin-it’s leptin resistance. Your brain is drowning in the signal but can’t hear it anymore.The Hormones That Fool Your Brain

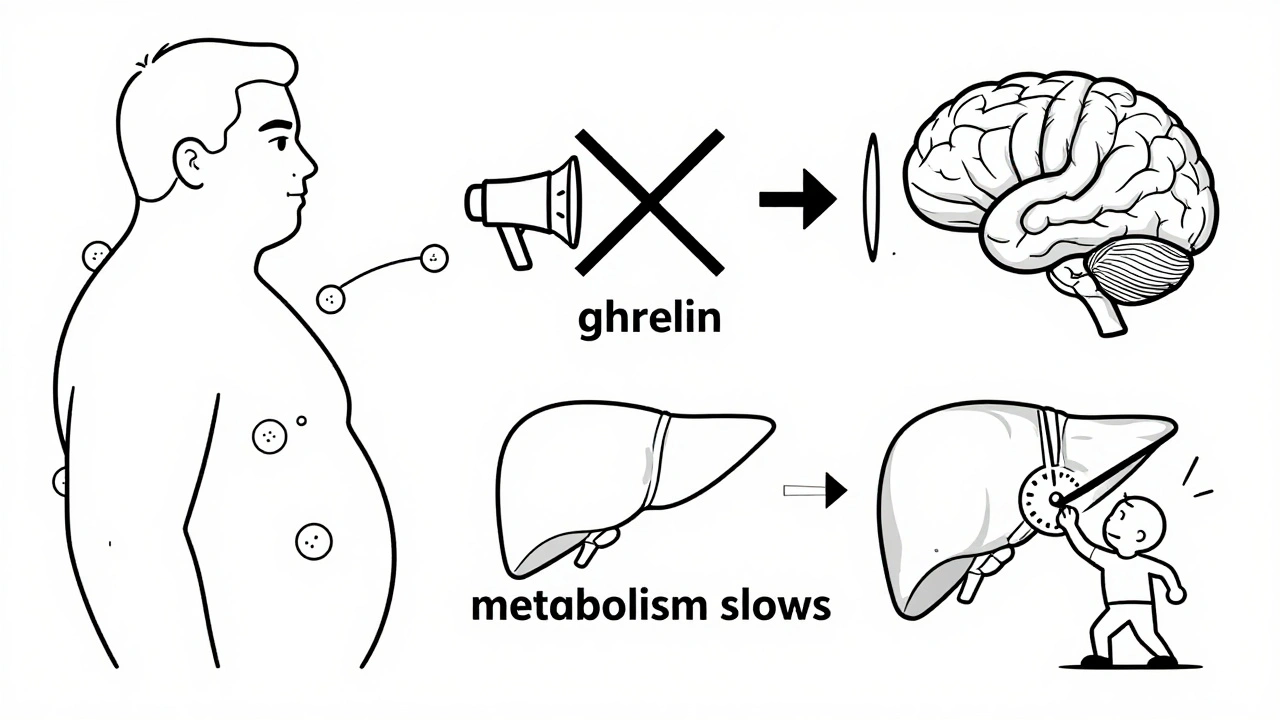

Leptin isn’t the only hormone involved. Insulin, which rises after meals, also tells your brain to reduce hunger. But in obesity, insulin’s message gets muffled too. Ghrelin, the “hunger hormone,” does the opposite. It spikes before meals-from 100-200 pg/mL when you’re fasting to 800-1,000 pg/mL right before you eat. In people with obesity, ghrelin doesn’t drop as it should after eating, so hunger lingers. Then there’s pancreatic polypeptide (PP), released after meals to slow digestion and reduce appetite. But in 60% of people with diet-induced obesity, PP levels are abnormally low-15-25 pg/mL instead of the normal 50-100 pg/mL. That means your body isn’t sending the “I’m done” signal properly. Even serotonin, a neurotransmitter linked to mood, plays a role. Some studies say it works through the 5HT2C receptor to activate POMC neurons. Others argue it’s the 5HT1B receptor that shuts down NPY neurons. The debate continues, but one thing is clear: messing with these brain chemicals changes how much you eat.

Why Your Body Resists Weight Loss

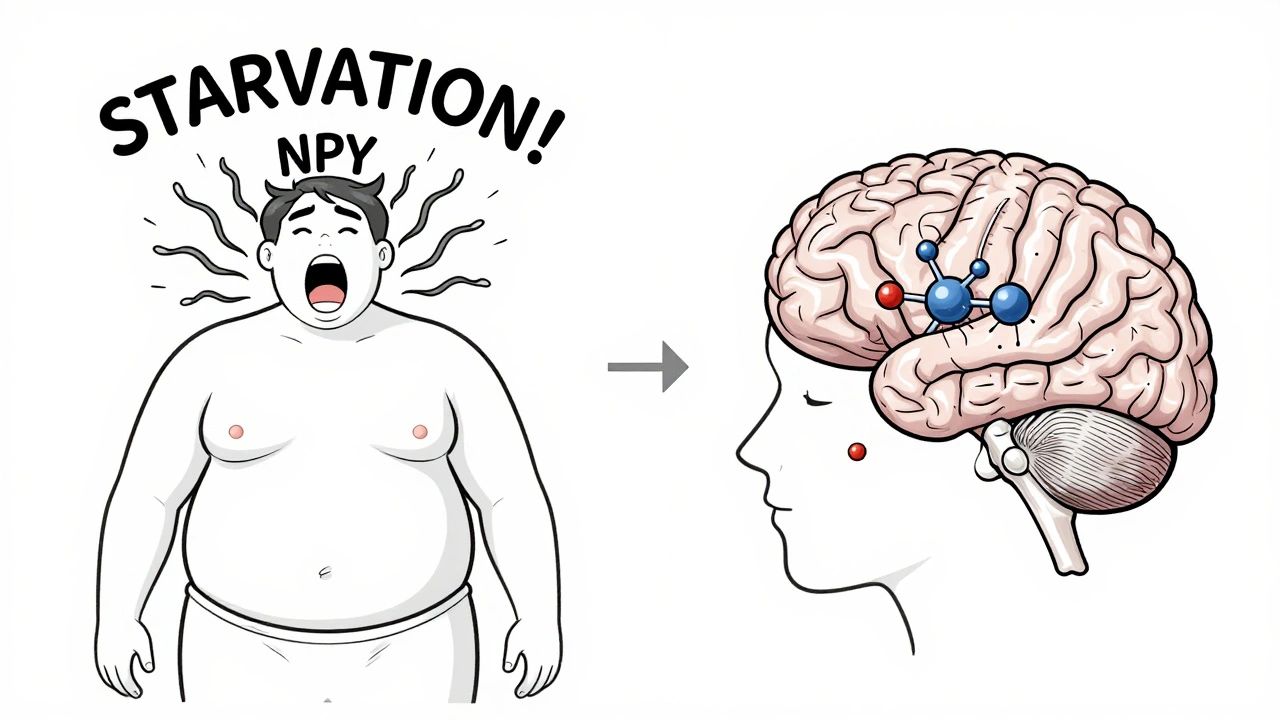

When you lose weight, your body doesn’t see it as a win-it sees it as a threat. Your fat cells shrink, so leptin drops. Your stomach produces more ghrelin. Your brain interprets this as starvation. The NPY/AgRP neurons go into overdrive. Your metabolism slows down. You feel hungrier. You burn fewer calories. This isn’t a failure of willpower. It’s biology. Studies show that after weight loss, leptin levels remain low for months-even years-keeping hunger signals high. That’s why most people regain weight. The system is still stuck in “famine mode.” Even the pathways that should help are broken. The PI3K/AKT pathway, which links leptin and insulin signals to appetite control, becomes less responsive in obesity. Inhibiting this pathway in mice completely blocks leptin’s ability to reduce eating. The mTOR system, which normally helps regulate energy balance, also falters. And inflammation from excess fat activates JNK, a protein that blocks leptin signaling even more.Metabolic Dysfunction: More Than Just Fat

Obesity isn’t just about storing fat-it’s about how your body uses energy. Fat tissue in obese individuals doesn’t just sit there. It releases inflammatory molecules that disrupt insulin sensitivity, leading to type 2 diabetes. It also alters how your liver processes glucose and how your muscles burn fuel. Brown fat, the kind that burns calories to make heat, becomes less active. In fact, mice genetically engineered to block PI3K signaling in fat tissue end up with more brown fat and lose 15% to 20% of their body weight-even though they eat more. That shows how tightly appetite and energy expenditure are linked. Hormones like estrogen also play a role. After menopause, women often gain belly fat quickly. Studies on mice without estrogen receptors show they eat 25% more and burn 30% less energy. That’s why weight gain after menopause isn’t just about aging-it’s hormonal.

What’s New in Treatment?

The old advice-“eat less, move more”-doesn’t fix broken biology. But new drugs are finally targeting the root causes. Setmelanotide, a drug that activates the melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R), works wonders in rare genetic cases of obesity caused by POMC or LEPR mutations. In trials, patients lost 15% to 25% of their body weight. It’s not for everyone, but it proves that fixing the brain’s appetite circuit can work. Semaglutide, originally a diabetes drug, mimics GLP-1, a gut hormone that slows digestion and signals fullness. In the STEP-1 trial, people lost an average of 15% of their weight. It doesn’t just reduce hunger-it makes food less rewarding. You still eat, but you don’t crave it as much. The biggest breakthrough came in 2022, when scientists found a group of excitatory neurons right next to the hunger and fullness neurons in the arcuate nucleus. When they turned these on in mice, eating stopped within two minutes. This opens the door to therapies that could override the broken signals without blocking them.Why This Matters

Obesity affects 42.4% of U.S. adults and is linked to 2.8 million deaths worldwide each year. The U.S. spends $173 billion annually treating its complications. We can’t treat it like a moral failing. We need to treat it like the chronic disease it is. The science is clear: appetite regulation and metabolic dysfunction are deeply intertwined. Your brain isn’t broken because you overeat. You overeat because your brain has been hijacked by faulty signals. Understanding this isn’t about blaming or shaming. It’s about building better tools. The next generation of drugs won’t just suppress hunger-they’ll reset the system. And for the millions living with this condition, that’s not just science. It’s hope.Is obesity caused by eating too much?

No, not in the way most people think. While overeating contributes, the real issue is a biological malfunction. In obesity, the brain’s appetite control system becomes resistant to signals like leptin and insulin. This leads to constant hunger, reduced fullness, and a slower metabolism-even when calorie intake is controlled. It’s not a lack of discipline; it’s a broken feedback loop.

What is leptin resistance?

Leptin resistance happens when your brain stops responding to leptin, the hormone your fat cells release to signal fullness. In obesity, leptin levels are high-sometimes double or triple normal-but the brain doesn’t “hear” it. This tricks your body into thinking it’s starving, triggering hunger and slowing metabolism. It’s the main reason weight loss is so hard to sustain.

Why do I feel hungrier after losing weight?

After weight loss, your fat cells shrink and produce less leptin. Your stomach makes more ghrelin-the hunger hormone. Your brain interprets this as a threat and turns up hunger signals while lowering your metabolic rate. This is an evolutionary survival mechanism. It’s not your fault-it’s biology trying to restore what it sees as lost energy stores.

Can medications fix obesity?

Yes, but not by magic. Drugs like semaglutide and setmelanotide target specific brain pathways to reduce hunger and increase fullness. Semaglutide mimics a gut hormone that tells your brain you’re full. Setmelanotide activates the melanocortin-4 receptor, which is broken in some genetic forms of obesity. These aren’t quick fixes-they work best with lifestyle support and are most effective when the underlying biology is understood.

Are there gender differences in obesity pathophysiology?

Yes. Estrogen plays a key role in regulating appetite and energy use. After menopause, when estrogen drops, women often gain belly fat quickly and experience increased hunger. Studies in mice without estrogen receptors show they eat 25% more and burn 30% less energy. This explains why weight gain after menopause is common and why treatments may need to be gender-specific.

Is obesity genetic?

For most people, obesity isn’t caused by a single gene. But genetics influence how your body responds to food, how sensitive you are to hunger signals, and how easily you store fat. Rare mutations in genes like POMC or LEPR cause severe obesity in fewer than 50 known cases worldwide. But common obesity results from many genes interacting with environment-especially a diet high in processed, calorie-dense foods.

What’s the future of obesity treatment?

The future is combination therapy. Instead of targeting just one pathway, new drugs are being designed to hit multiple systems at once-appetite, metabolism, fat burning, and even brain reward circuits. Over 17 compounds are currently in late-stage trials. The goal isn’t just weight loss-it’s resetting the body’s weight regulation system so it stays stable long-term.

All Comments

Ollie Newland December 4, 2025

So it's not just willpower? That makes so much sense. I always felt like a failure when I'd lose weight and then gain it back, but now I realize my brain was literally fighting me. Leptin resistance is wild-imagine your body drowning in a signal but going deaf. It's like having a fire alarm that's constantly blaring but you've trained yourself to ignore it.

Martyn Stuart December 5, 2025

Exactly-this isn't a moral failing; it's neuroendocrine dysfunction. The arcuate nucleus is a biological control tower, and in obesity, it's receiving corrupted data from adipose tissue, the gut, and the pancreas. Leptin resistance? It's not a deficiency-it's receptor desensitization. Insulin resistance follows the same pattern. The PI3K/AKT pathway is downregulated, and JNK inflammation further inhibits signaling. This is a systemic failure, not a behavioral one.

Jessica Baydowicz December 5, 2025

OMG I finally feel seen. I’ve been told ‘just eat less’ for years, but after my third round of weight loss and regain, I realized my body was screaming ‘FAMINE’ even when I was eating 1,800 calories. The ghrelin spike after meals? The energy crash? It’s not laziness-it’s biology screaming for survival. I’m so tired of being shamed. Thank you for putting this into words.

Shofner Lehto December 6, 2025

Setmelanotide and semaglutide are game-changers, but they’re not magic pills. They’re tools that work because they’re targeting the actual broken circuits. The fact that we’re finally moving beyond ‘calories in, calories out’ is huge. This is the kind of science that needs to be taught in med schools and high schools alike.

George Graham December 7, 2025

I’ve watched my mom struggle with weight after menopause. The belly fat came out of nowhere, and no matter how much she walked or cut carbs, it wouldn’t budge. Now I get why-estrogen isn’t just about reproduction. It’s a metabolic regulator. Her body was burning less, craving more, and no amount of discipline could fix that. This article didn’t just explain her struggle-it explained my family’s history.

John Filby December 8, 2025

Wait-so those new excitatory neurons that shut down eating in 2 minutes? That’s insane. Like a biological off-switch. If we could safely activate those in humans, we wouldn’t need drugs that just nudge the system-we’d be rebooting it. Imagine a therapy that doesn’t suppress hunger but overrides it. That’s next-level.

Ben Choy December 10, 2025

Bro, I’ve been on semaglutide for 6 months. I don’t crave junk food anymore. Not because I’m strong-it’s because my brain stopped screaming for sugar. I still eat, but food doesn’t feel like a reward. It’s just fuel. This isn’t ‘cheating’-it’s fixing a broken system. If you’ve ever felt guilty for wanting food, know this: it’s not you. It’s biology.

Emmanuel Peter December 11, 2025

So you’re saying we should just give people drugs and call it a day? What about personal responsibility? If your brain’s broken, why not fix it with discipline? You’re just giving people an excuse to be lazy.