When you take a generic medication, you expect the same results as the brand-name version - and you should. But what if something unusual happens? A rash that won’t go away. A sudden dizzy spell. Unexplained joint pain. These aren’t common. They’re rare. And if you’ve experienced one, you might wonder: Should I report it? The answer is yes - and here’s why, and how.

Generics aren’t second-class drugs - but their side effects still matter

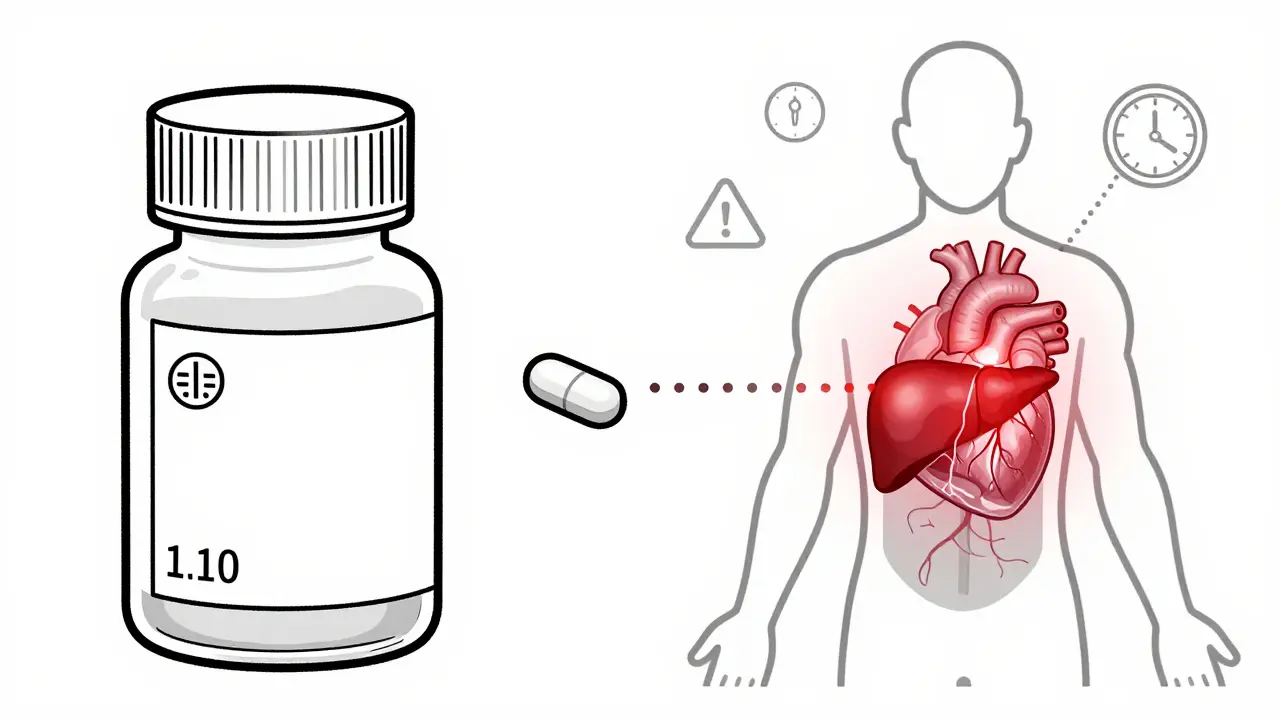

Many people think generic drugs are somehow less monitored than brand-name ones. That’s not true. Under U.S. law, generic medications must contain the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the original. The FDA requires them to be bioequivalent - meaning they work the same way in your body. That also means they carry the same potential for side effects. But here’s the catch: rare adverse events often don’t show up in clinical trials. Those studies involve a few thousand people at most. Real-world use? Millions. And when you scale up, you start seeing things that didn’t appear before - like a spike in liver enzyme changes with a specific batch of generic statins, or sudden QT prolongation with a certain generic version of citalopram. The FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) has over 25 million reports. And guess what? 98.7% of those reports don’t even distinguish between brand and generic because the active ingredient is identical. That’s why reporting matters - whether you took the name brand or the $4 version at the pharmacy.What counts as a rare adverse event?

The FDA defines rare adverse events as reactions occurring in fewer than 1 in 1,000 patients based on clinical trial data. But post-marketing surveillance often finds even rarer ones - 1 in 10,000, or even 1 in 50,000. These aren’t just oddities. They can be serious. Examples include:- Stevens-Johnson Syndrome with generic lamotrigine (reported at 1.8 cases per 10,000 person-years, higher than clinical trials suggested)

- Acute liver injury within weeks of starting generic simvastatin

- Arthralgia (joint pain) linked to generic levetiracetam - over 40 reports prompted an FDA safety review

- QT prolongation with generic citalopram, leading to updated dosing limits for patients over 60

When to report - even if you’re not sure

You don’t need to be certain. The FDA says: report even if you’re unsure. In fact, 68.4% of major safety findings started as reports where causality was unclear. Here’s when to act:- No other explanation: You started the generic drug, and within days or weeks, you got a reaction that doesn’t match your medical history. No infection. No new food. No change in other meds. That’s a red flag.

- Timing fits: Liver injury from statins usually shows up 1-6 weeks after starting. Angioedema from ACE inhibitors? Often within hours or days. If the timeline matches, report it.

- It’s unexpected: If the side effect isn’t listed in the drug’s package insert, it’s unexpected - and that triggers expedited reporting. Even if it’s not listed, if it’s serious, report it.

How to report - the simple 5-step process

Reporting isn’t complicated. Here’s what to do:- Write down the details: Date you started the drug, exact name (including manufacturer if you know it), dose, and how long you took it. Note any other medications you’re on - even supplements.

- Track symptoms: When did they start? How bad? Did they get worse? Did they improve after stopping the drug? (This is called dechallenge.) Did they return if you took it again? (Rechallenge.)

- Check the label: Look at the side effect list in the packaging or online. Is your symptom listed? If not, it’s unexpected - and that’s important.

- Choose your form: If you’re a healthcare provider, use MedWatch Form 3500. If you’re a patient, use Form 3500B. Both are free and available online or by phone.

- Submit within 15 days: For serious, unexpected reactions, the law requires reporting within 15 calendar days. Don’t delay. The sooner it’s in the system, the sooner others are protected.

Why your report matters - even if you’re just a patient

Most reports come from doctors. But only 28.7% of patient-submitted reports have enough detail to be useful. Why? People leave out key info: lot numbers, exact drug names, timing, or other meds. That’s a problem. Lot numbers are critical. Two different manufacturers might make generic metformin - one could have a bad batch causing hypoglycemia, while another doesn’t. Without the lot number, the FDA can’t trace it. In 2022, the FDA’s Sentinel Initiative used electronic health records from 300 million people to spot new safety signals. They found seven new risks tied to generic drugs - including a specific metformin formulation linked to low blood sugar. That discovery came from aggregated reports. Your report could be the one that triggers the next safety update.What’s being done to fix the gaps

The FDA knows reporting is uneven. In 2023, they launched a new action plan to boost high-quality reports by 25% by 2025. They’re simplifying the online form, training pharmacists to ask patients about side effects, and pushing manufacturers to report electronically - which became mandatory in December 2025 under FDASIA. They’re also improving how they track inactive ingredients. Lactose, dyes, and fillers in generics can trigger reactions in sensitive people. But only 15.3% of reports mention these. That’s changing. New labeling requirements will soon force manufacturers to list all excipients clearly. AI is helping too. Machine learning now scans FAERS data and flags potential issues 4.8 months faster than human review. That means faster warnings, faster recalls, and fewer people hurt.

What you can do today

You don’t need to be a doctor. You don’t need to be an expert. You just need to pay attention.- Keep your medication list updated - including generics and lot numbers.

- Ask your pharmacist: “Is this the same as last time?” If the pill looks different, ask why.

- If you feel something off, write it down. Date. Time. Symptom. Did it start after the new prescription?

- Don’t assume it’s “just a side effect.” If it’s rare, unusual, or scary - report it.

Do I need to report side effects from generic drugs if they’re the same as the brand-name version?

Yes. Even though generics have the same active ingredient, side effects can still vary due to differences in inactive ingredients, manufacturing processes, or batch quality. Every report helps the FDA detect patterns. If a specific generic version causes more reactions than others, reporting is the only way to find out.

What if I’m not sure the generic caused the side effect?

Report it anyway. The FDA doesn’t require proof - just reasonable suspicion. In fact, two-thirds of major drug safety findings started as reports where causality was uncertain. Your report could be the first clue in a larger pattern.

Do I need to include the lot number when reporting?

Yes, if you can find it. Lot numbers are printed on the bottle or packaging. They’re critical for identifying if a specific batch is problematic. Only 12.4% of patient reports include them - but those are the reports that lead to recalls. Don’t skip this step.

Can I report side effects for someone else, like an elderly parent?

Absolutely. Family members, caregivers, and even pharmacists can file reports on behalf of patients. Just include as much detail as possible - the patient’s age, medical conditions, and the exact medication name and dose.

Are generic drugs less safe than brand-name drugs?

No. The FDA requires generics to meet the same standards for safety, strength, and quality as brand-name drugs. Studies show no significant difference in overall adverse event rates. But because generics are used far more often, rare events are more likely to be detected - which is why reporting is so important.

How long does it take for a report to lead to a drug warning or recall?

It varies. Some signals are confirmed within months; others take years. The FDA uses AI and data from millions of patients to spot trends. Once a pattern is clear - like the QT prolongation with citalopram - they update the label, issue a safety alert, or restrict dosing. Your report is part of that process.

What happens after you report?

Once you submit, your report goes into the FDA’s database. It’s anonymized. It’s combined with thousands of others. Analysts look for clusters: same drug, same symptom, same manufacturer. If enough reports point to a problem, the FDA investigates further - maybe with lab tests, or by reviewing manufacturing records. If they find a real risk, they can:- Update the drug’s label with new warnings

- Issue a public safety alert

- Require the manufacturer to change the formulation

- Ask for a voluntary recall of a specific lot

All Comments

Samar Khan December 28, 2025

OMG I took that generic lamotrigine last year and got this crazy rash that looked like someone poured hot sauce on my skin 😱 I thought it was stress until I read this. I didn't report it because I was scared they'd think I'm crazy. Now I'm so mad I didn't. Someone could die because I stayed quiet.

Russell Thomas December 30, 2025

Wow. Another ‘your report matters’ guilt trip. Newsflash: the FDA has more data than your grandma’s recipe box. You think your 3-day headache is a ‘rare adverse event’? Nah. You’re just sensitive. Also, why are we still using paper forms in 2025? 😴

Joe Kwon January 1, 2026

Appreciate the breakdown of FAERS and the distinction between active vs. excipient-driven AEs. The real gap isn't reporting-it's granularity in data capture. Lot numbers, excipient profiles, and batch-level metadata are critical for signal detection. We're still operating on a 1980s framework while AI models are ready to parse 10M+ records. The FDA's 2025 mandate is a step, but real progress needs interoperability with EHRs. #Pharmacovigilance #RealWorldEvidence

Jasmine Yule January 1, 2026

I reported a weird joint pain after switching to generic levetiracetam and got ZERO response. Zero. Like my pain was invisible. And now I’m supposed to feel good about this? I’m not a data point-I’m a person who lost three weeks of work. If this system doesn’t even acknowledge you, why should I keep trying? 😔

Jim Rice January 3, 2026

So... you're telling me that a $4 pill can kill me but the $100 version won't? That's not science-that's corporate witchcraft. I bet the brand-name makers are the ones lobbying to keep us from reporting. Who profits if we know the generics are dangerous? Hmm?

Henriette Barrows January 4, 2026

Hey, I just started a new generic and noticed my hands are shaking a little. I didn't think much of it, but now I'm gonna write down the date, the lot number from the bottle, and call my pharmacist tomorrow. I never knew how much power we had in this system. Thanks for the nudge 💙

Alex Ronald January 5, 2026

For anyone new to this: if you're on a generic statin and notice unexplained fatigue or dark urine, get liver enzymes checked ASAP. I had a patient whose ALT spiked to 400 after switching to a new generic simvastatin batch. We pulled the bottle-lot #B7X92. FDA flagged 11 other reports with that same lot. That’s how it starts. Your documentation saves lives.

Teresa Rodriguez leon January 6, 2026

I’ve been taking generics for 15 years. Never had a problem. You people act like every pill is a landmine. Stop being dramatic. The FDA doesn’t need your emotional rants. Just take your meds and move on.

Manan Pandya January 6, 2026

Excellent guide. I’ve trained community health workers in rural India to document adverse events using this exact framework. We emphasize three things: exact drug name (including manufacturer), timing of symptom onset, and discontinuation effect. One report from a village led to the recall of a contaminated metformin batch. Your voice matters-even if you’re far from Washington.

Aliza Efraimov January 7, 2026

My mom had Stevens-Johnson after a generic lamotrigine. She was in the ICU for 47 days. We reported it. Nothing happened. No one called. No apology. No warning. Just silence. And now? Her skin still peels in the sun. Don’t tell me ‘your report matters’ when the system ignores the people who actually need it. This isn’t activism-it’s survival.

Nisha Marwaha January 9, 2026

Excipient sensitivity is the elephant in the room. Lactose, FD&C dyes, magnesium stearate-these aren’t inert. I’ve seen patients with autoimmune disorders react to fillers in generics while tolerating brand-name versions perfectly. The FDA’s new labeling requirements are overdue. Pharmacies need to train staff to ask: ‘Has this pill changed?’ Not just ‘Is it cheaper?’

Paige Shipe January 10, 2026

So you’re saying I need to report every little thing? I got a headache once after taking a generic. Should I file a federal form? Please. This is just fear-mongering dressed up as public health. I’m not your lab rat. And if you think I’m writing down lot numbers, you’re delusional.

Tamar Dunlop January 10, 2026

While I appreciate the thoroughness of this exposition, I must respectfully underscore the ontological distinction between pharmacovigilance as a public good and the individual’s epistemic burden. The asymmetry of power between the patient-reporter and the regulatory apparatus remains profoundly unaddressed. One wonders whether the onus of vigilance ought not to be borne by the manufacturer, not the citizen. A Canadian perspective, for what it is worth.

David Chase January 10, 2026

HAHAHAHA! You people actually believe this? The FDA is a puppet of Big Pharma. They don’t care about you. They care about profits. You think your report will change anything? Nah. It’ll just get buried in a database with 25 million other lies. And you know what? I’m not reporting anything. I’m done playing their game. America is dying because of this crap. 💥🇺🇸