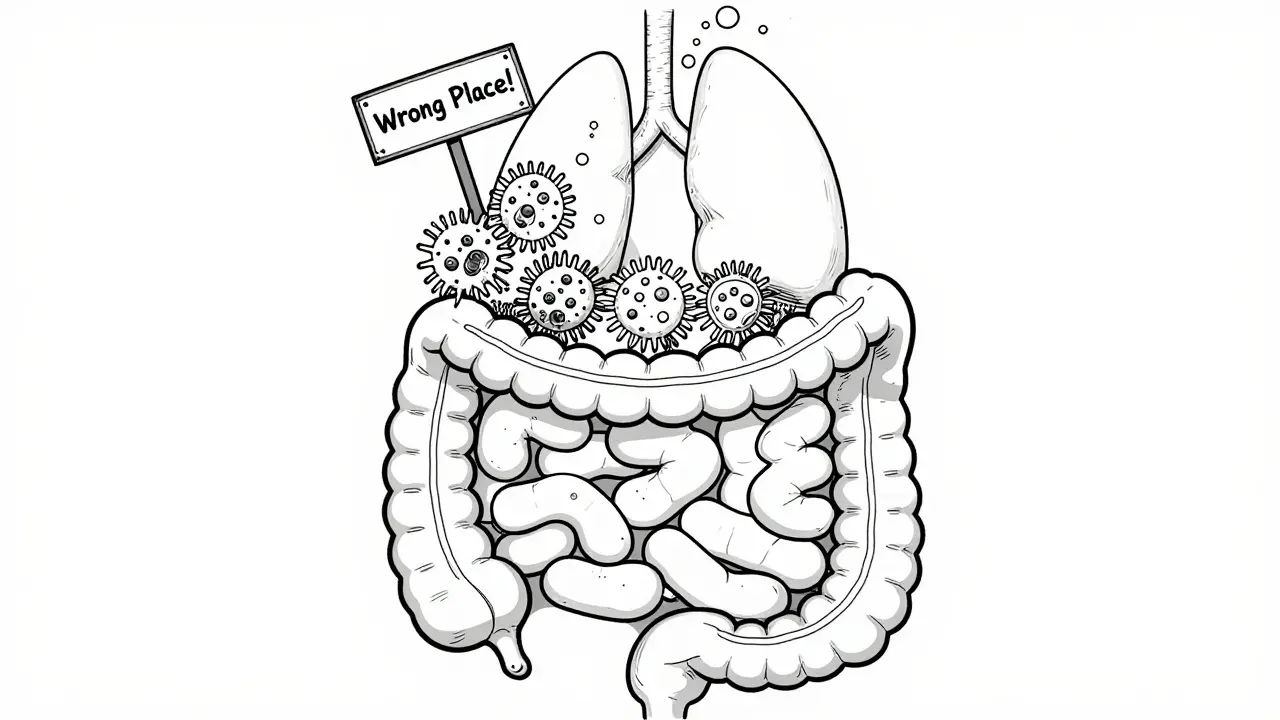

If you’ve been struggling with bloating, gas, diarrhea, or constipation that won’t go away-even after cutting out gluten or dairy-you might be dealing with something deeper than just a food sensitivity. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth, or SIBO, is a hidden condition that affects millions but is often missed or misdiagnosed as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Unlike normal gut bacteria that live in the colon, SIBO happens when too many bacteria grow where they shouldn’t: in the small intestine. This disrupts digestion, damages the gut lining, and steals nutrients your body needs. The good news? There are clear ways to test for it-and treat it.

How SIBO Develops

Your small intestine isn’t meant to host large numbers of bacteria. That’s the colon’s job. But when the natural cleanup system fails-like the migrating motor complex (MMC) that sweeps bacteria downstream-bacteria start to multiply where they don’t belong. This isn’t random. It usually happens because something has slowed down your gut movement or changed the environment.Common causes include past abdominal surgery, especially bowel resections or gastric bypass. About 30-50% of people who’ve had this kind of surgery develop SIBO. Long-term use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), like omeprazole, also raises your risk by 2-3 times. These drugs reduce stomach acid, which normally kills off harmful bacteria before they reach the small intestine.

Other triggers include diabetes, scleroderma, and cirrhosis. Even IBS has a strong link-up to 85% of people with IBS test positive for SIBO, depending on the test used. If your symptoms flare up after eating carbs, especially sugars or fiber, that’s a big red flag. Bacteria feed on these, producing gas that causes bloating, pain, and changes in bowel habits.

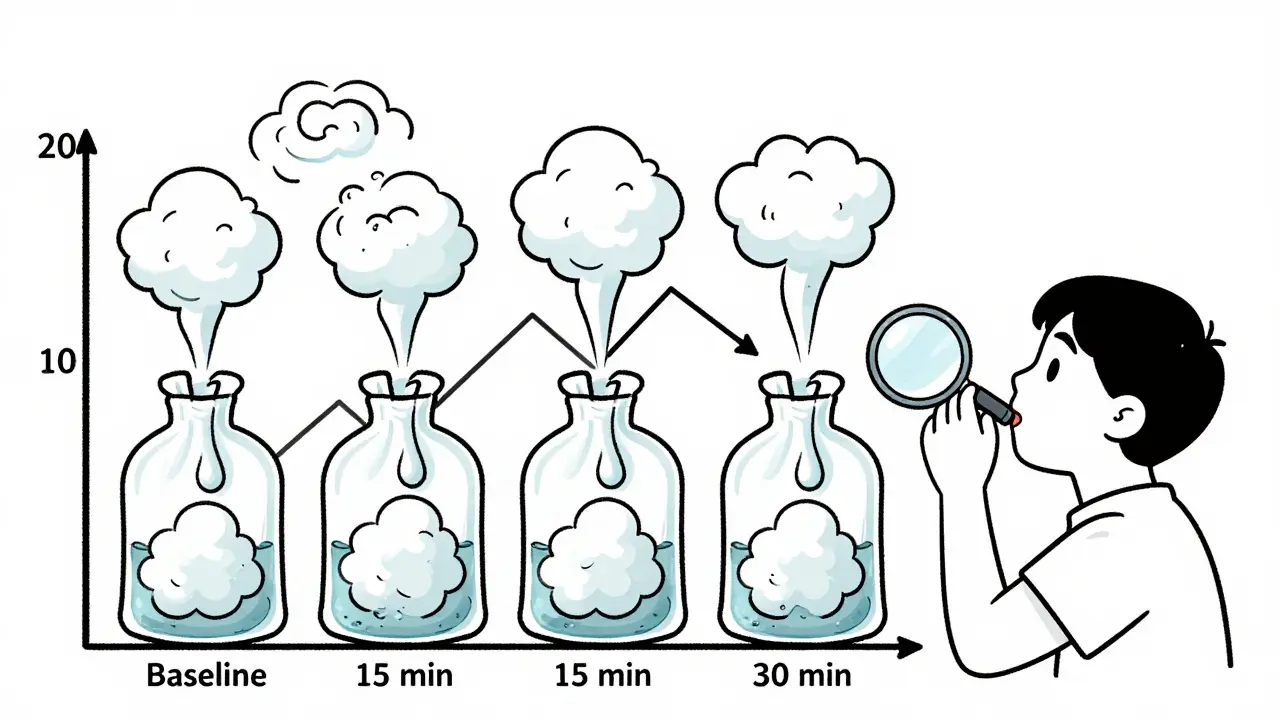

How Breath Tests Work

The most common way to check for SIBO is a breath test. It sounds simple: you drink a sugary solution and blow into a bag every 15-20 minutes for up to two hours. But the science behind it is precise.The test looks for gases produced by bacteria: hydrogen and methane. When bacteria ferment sugar in the small intestine, they release these gases, which get absorbed into your blood and exhaled through your lungs. A rise of 20 parts per million (ppm) in hydrogen or 10 ppm in methane above your baseline level within 90-120 minutes usually means SIBO is present.

There are two main types of sugar used: glucose and lactulose. Glucose is absorbed quickly in the first part of the small intestine, so it’s better at detecting overgrowth near the top. Lactulose moves further down, so it can catch bacteria in the lower small intestine. But here’s the catch: glucose tests miss about half of SIBO cases because the sugar gets used up too soon. Lactulose catches more cases but gives more false positives-especially in people with fast gut movement.

According to a 2019 analysis of 17 studies, lactulose breath tests have a sensitivity of 62% and specificity of 71%. Glucose tests are more specific (83%) but only catch 46% of real cases. That means you could get a negative result even if you have SIBO.

Why Breath Tests Can Be Misleading

Breath tests are convenient and non-invasive, but they’re far from perfect. About 15-20% of people don’t produce hydrogen at all. These “non-hydrogen producers” might only make methane or even hydrogen sulfide-which current breath tests can’t detect. That’s why some people keep having symptoms even after a “negative” test.Another problem? Rapid transit. If your food moves too quickly through your gut, the sugar reaches the colon before it should. That triggers a gas spike that looks like SIBO-but it’s just normal colonic fermentation. This happens in 10-15% of cases and leads to false positives.

And then there’s the issue of interpretation. One lab might call a 15 ppm rise in hydrogen positive. Another waits for 20 ppm. Some don’t even test for methane. That’s why two people with identical symptoms can get totally different results depending on where they test.

Dr. Eamonn Quigley, former president of the American College of Gastroenterology, calls breath tests a “screening tool,” not a diagnosis. That means if your test is positive, it’s a signal to dig deeper-not a final answer.

The Gold Standard: Fluid Culture

The only way to confirm SIBO with certainty is to take a fluid sample directly from the small intestine during an endoscopy. A doctor passes a tube through your mouth, past the stomach, and into the jejunum (the middle part of the small intestine). They collect 3-5 milliliters of fluid and send it to a lab to count bacteria. If there are more than 100,000 colony-forming units per milliliter (CFU/mL), it’s SIBO.This method is accurate-but rarely used. Why? It’s expensive ($1,500-$2,500), invasive, and not widely available. Only a handful of centers, like UC Davis Health, do it routinely. Dr. Hisham Hussan, who leads their endoscopy program, says breath tests are only about 60% accurate. That means 4 in 10 people are misdiagnosed.

The real advantage of fluid culture? It can tell you exactly which bacteria are overgrowing-and which antibiotics they’re sensitive to. Breath tests can’t do that. If you’ve had SIBO before and it came back after treatment, a culture might show you why.

What Happens After a Positive Test?

If your breath test is positive and your symptoms match, treatment usually starts with antibiotics. The most common is rifaximin (Xifaxan), taken at 1,200 mg per day for 10-14 days. It’s not absorbed into your bloodstream-it stays in your gut and kills bacteria where they are.Studies show 40-65% of people improve after one course. But here’s the problem: more than 40% relapse within nine months. Why? Because antibiotics don’t fix the root cause. If your gut motility is still slow, or your stomach acid is still low, bacteria will grow back.

For methane-dominant SIBO (often linked to constipation), doctors often combine rifaximin with neomycin. This combo works better than rifaximin alone. Some clinics also use herbal antimicrobials like oregano oil, berberine, or garlic extract-especially for people who can’t tolerate antibiotics or want to avoid them.

After antibiotics, diet plays a big role. Low-FODMAP, Specific Carbohydrate Diet (SCD), or GAPS diets are often recommended to starve the bacteria. But these aren’t long-term fixes. They help during treatment, but once you reintroduce foods, symptoms can return if the underlying issue isn’t resolved.

Preventing SIBO From Coming Back

To keep SIBO away, you need to fix what caused it in the first place. That might mean:- Stopping or reducing PPIs if you’re on them long-term

- Taking prokinetic medications like low-dose erythromycin or prucalopride to boost gut motility

- Addressing low stomach acid with betaine HCl (under medical supervision)

- Managing underlying conditions like diabetes or thyroid disorders

- Using digestive enzymes or bile acid binders if needed

Some people benefit from intermittent fasting or eating three meals a day with no snacks. This gives your gut time to activate the migrating motor complex, which naturally cleans out bacteria between meals.

Re-testing after treatment is important. Many clinics recommend a follow-up breath test 2-4 weeks after finishing antibiotics to see if the overgrowth cleared. But remember: a negative test doesn’t always mean you’re cured. If your symptoms are gone, that’s often more important than the number on the report.

The Future of SIBO Testing

New technology is on the horizon. Researchers at Cedars-Sinai and Mayo Clinic are developing breath analyzers that can detect hydrogen sulfide, a gas many current tests miss. Others are working on wireless capsules that measure gas levels directly inside the gut-no breath samples needed.In June 2024, Dr. Mark Pimentel’s team announced a phase 2 trial of a new breath analyzer predicted to be 85% accurate. If successful, it could become the new standard.

For now, though, breath testing remains the most practical option. It’s accessible, affordable, and widely available. But it’s not a magic bullet. It’s a tool-and like any tool, it works best when used wisely, with the right preparation and interpretation.

How to Prepare for a Breath Test

Getting an accurate result depends almost entirely on how well you prepare. Here’s what you need to do:- Fast for 12 hours before the test-only water allowed

- Avoid antibiotics for at least 4 weeks

- Stop laxatives and prokinetics (like domperidone or prucalopride) for 7 days

- Follow a low-residue diet for 24-48 hours before: no beans, broccoli, dairy, fruit, or whole grains

- Don’t smoke, exercise, or sleep during the test

- Stay seated and calm during the 2-hour testing window

Many people fail their test not because they have SIBO, but because they didn’t follow the rules. One study found that 25-30% of inconclusive results were due to poor preparation.

If you’re constipated, you may need extra prep time. Some clinics recommend a 3-day diet and even a bowel cleanse before testing.

When to Ask for a Second Opinion

If you’ve been told you have SIBO but don’t respond to treatment, or if your symptoms are getting worse, it’s time to dig deeper. Ask your doctor:- Was methane tested? (If not, demand it)

- What was the exact gas rise used to define a positive result?

- Have you considered a small bowel aspirate?

- Could my symptoms be from something else-like bile acid malabsorption or celiac disease?

SIBO is real. But it’s not the only reason for chronic digestive issues. Don’t let a single test define your health journey.

All Comments

suhani mathur December 23, 2025

So let me get this straight-you drink sugar water, blow into a bag, and suddenly you’re told your gut is a bacterial rave? I’ve had three of these tests. Two were negative, one was ‘borderline methane,’ and I still can’t eat an apple without turning into a balloon. Meanwhile, my doc keeps prescribing more antibiotics like they’re Skittles. 😒

Also, why is everyone acting like SIBO is the new Lyme disease? I get it’s real-but it’s not a magic bullet for every bloated person who ate too much kale.

Georgia Brach December 24, 2025

The assertion that lactulose breath tests have a sensitivity of 62% is misleading without context. The study cited (2019 meta-analysis) pooled heterogeneous populations with varying inclusion criteria, and no correction was made for transit time variability. Moreover, the 71% specificity assumes perfect adherence to prep protocols, which in clinical practice is rarely achieved. The diagnostic accuracy of breath testing, therefore, is functionally indeterminate in real-world settings.

Furthermore, the reliance on gas thresholds (20 ppm H2, 10 ppm CH4) lacks physiological validation. These cutoffs are arbitrary, derived from cohort studies with no longitudinal correlation to symptom resolution. To treat based on these metrics is not evidence-based medicine-it is algorithmic superstition.

Katie Taylor December 26, 2025

STOP LETTING DOCTORS SCAM YOU. I had SIBO. I did the breath test. Negative. I went to a functional doc who did a 3-hour lactulose test with methane tracking. POSITIVE. I did 10 days of rifaximin + neomycin, low-FODMAP, and prokinetics. Bloating? Gone. Constipation? Fixed. I’m not ‘imagining it.’

If your doctor won’t test for methane or won’t listen, get a new doctor. Your gut isn’t a suggestion box. It’s screaming. Listen.

Bhargav Patel December 26, 2025

One is compelled to reflect upon the epistemological paradox inherent in the diagnostic paradigm of SIBO: the condition is defined by an excess of microbial presence in a region of the gastrointestinal tract that, by anatomical and physiological design, ought to remain largely sterile. Yet the tools employed to detect this excess are indirect, probabilistic, and subject to significant confounding variables-chief among them, transit time and microbial metabolic heterogeneity.

It is not merely a matter of bacterial overgrowth, but of the disruption of the homeostatic equilibrium between host physiology and microbial ecology. To reduce this to a binary ‘positive/negative’ breath test is to mistake the shadow for the object. The true pathology may lie not in the bacteria themselves, but in the failure of the migrating motor complex, the erosion of gastric acidity, or the dysregulation of bile flow-factors that remain unmeasured by current clinical instruments.

Thus, the pursuit of SIBO may be, in part, the pursuit of a symptom masked as a diagnosis. The remedy, then, must be holistic-not antimicrobial, but regenerative.

Steven Mayer December 28, 2025

The diagnostic utility of breath testing is confounded by the absence of standardized calibration protocols across commercial labs. The inter-assay variability in gas detection thresholds-particularly for methane-is not merely technical, but systemic. Moreover, the pharmacokinetic profile of rifaximin, while ostensibly gut-restricted, exhibits low but measurable serum absorption in up to 12% of patients with impaired intestinal barrier integrity, raising concerns regarding off-target microbiome perturbation.

Additionally, the assertion that herbal antimicrobials are ‘alternatives’ to antibiotics lacks rigorous pharmacodynamic characterization. Berberine, for instance, demonstrates dose-dependent inhibition of cytochrome P450 enzymes, potentially altering the metabolism of concomitant medications. The clinical literature on herbal regimens remains predominantly anecdotal, with no randomized controlled trials meeting CONSORT criteria for outcome reporting in SIBO recurrence.

Therefore, the current therapeutic landscape is characterized by empirical interventionism, not mechanistic precision.

Joe Jeter December 30, 2025

Everyone acts like SIBO is some new mystery disease, but it’s just the gut’s way of saying you’ve been abusing PPIs and eating sugar like it’s going out of style. I’ve seen this for 15 years. You don’t need a breath test-you need to stop taking acid blockers, stop snacking, and eat like a human who doesn’t live in a cafeteria.

Also, ‘low-FODMAP diet’ is just a fancy way of saying ‘eat white rice and chicken breast for 6 months.’ Congrats, you’ve invented the bland diet. We had that in the 1950s.

Lu Jelonek December 30, 2025

As someone who lived in Japan for five years and studied traditional gut health practices, I’ve seen how fermented foods and mindful eating patterns naturally regulate intestinal flora. The Western obsession with testing and antibiotics misses the point: the body is designed to self-regulate when given the right environment.

Try this: eat slowly, chew thoroughly, avoid eating within 3 hours of bed, and include small amounts of miso or natto daily. No breath test needed. Just patience and presence.

It’s not about killing bacteria. It’s about inviting balance.

Ademola Madehin December 31, 2025

YOOOO I had SIBO and it was THE WORST. Like, I was bloated so bad I looked 7 months pregnant. Tried everything. Antibiotics? Made me feel like a zombie. Herbal stuff? Tasted like dirt. Then I did a 3-day fast and just ate bone broth for a week. POOF. Gone.

Also, my mom said I was just stressed. She was right. My gut was crying for a nap. 🤡

Now I do yoga, drink ginger tea, and refuse to eat after 7pm. SIBO didn’t beat me. I beat SIBO. #GutWarrior

Andrea Di Candia January 2, 2026

I think what’s beautiful here is how this post bridges science and lived experience. We’re not just talking about bacteria-we’re talking about people who’ve been dismissed for years, told it’s ‘just anxiety’ or ‘all in their head.’

And yet, even as we push for better diagnostics and treatments, let’s not lose sight of the fact that healing isn’t linear. Some days, you eat a salad and feel fine. Other days, a single bite of avocado feels like a betrayal.

Maybe the real breakthrough isn’t a new breath analyzer, but a healthcare system that listens before it tests.

Dan Gaytan January 2, 2026

YES. THIS. I’ve been on this journey for 4 years. 3 breath tests. 2 rounds of antibiotics. 1 failed herbal protocol. I cried in the doctor’s office last month because I was so tired of being told I was ‘fine’ when I wasn’t.

Then I found a functional GI doc who actually listened. We did a methane test (which the first doc refused to run). Positive. We tried low-dose erythromycin + intermittent fasting. In 6 weeks? My bloating dropped 80%.

You’re not broken. You’re just misunderstood. Keep going. 🙌

Chris Buchanan January 4, 2026

Let’s be real-the whole SIBO industry is a goldmine for functional docs and supplement sellers. ‘Try this $89 herbal pack!’ ‘Get our $300 gut reset program!’ Meanwhile, the real fix? Stop eating processed crap, move your body, and sleep like your life depends on it (because it does).

Also, if you’re still on PPIs after 2 years? You’re not ‘managing reflux’-you’re creating a bacterial buffet. Time to wean off. Slowly. With help.

Stop paying for tests. Start paying attention.

Wilton Holliday January 4, 2026

To anyone reading this and feeling lost: you’re not alone. I was diagnosed with SIBO after 3 years of being told I was ‘just anxious.’ I thought I’d never eat bread again.

But here’s what changed: I stopped chasing the perfect test and started building a better routine. Walking after meals. Not snacking. Eating earlier. Taking magnesium. Drinking warm lemon water in the morning.

My breath test is still ‘positive.’ But my symptoms? Gone. Sometimes, healing isn’t about erasing bacteria-it’s about restoring rhythm.

You’ve got this. 💪

Raja P January 6, 2026

As an Indian guy who grew up eating spicy food and fermented rice, I never understood the Western panic over carbs. We’ve had dal, idli, dosa, yogurt for centuries. No breath tests. No antibiotics.

Maybe the problem isn’t the bacteria-it’s the food we’re feeding them. Processed sugar, fake fibers, constant snacking. That’s not traditional. That’s industrial.

Try eating three meals, no snacks, and see what happens. Your gut doesn’t need a lab report. It needs silence between meals.

Joseph Manuel January 7, 2026

The reliance on breath testing as a primary diagnostic modality for SIBO represents a significant epistemic failure in clinical gastroenterology. The absence of a validated gold standard for comparison renders all sensitivity and specificity metrics theoretically unstable. Furthermore, the proliferation of commercial testing kits without regulatory oversight (FDA Class II clearance is not equivalent to clinical validation) constitutes a form of diagnostic commodification.

Until prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials are conducted with standardized prep protocols and blinded interpretation, breath testing remains a hypothesis-generating tool at best-and a source of iatrogenic harm at worst.

Andy Grace January 8, 2026

My partner had SIBO. We did everything right: prep, fasting, no antibiotics for 4 weeks. Test came back negative. She still had symptoms. We went to a specialist who did a culture. Positive. 200,000 CFU/mL.

Turns out, her breath test was done at a chain clinic that doesn’t even test for methane. They just used glucose and called it a day.

Don’t trust the first test. Don’t trust the first doctor. Keep asking. Keep pushing. Your gut deserves better than a cookie-cutter protocol.