Most people don’t know they have subclinical hyperthyroidism until it shows up on a routine blood test. No weight loss. No jittery hands. No racing heart. Just a low TSH level-below 0.45 mIU/L-with everything else normal. It’s silent. But that doesn’t mean it’s harmless. Especially for older adults. Especially for the heart.

What Exactly Is Subclinical Hyperthyroidism?

Subclinical hyperthyroidism means your thyroid is working a little too hard, but not enough to push your T4 or T3 into the high range. Your TSH-the hormone your brain sends to tell your thyroid to slow down-is suppressed. That’s the only sign. It’s like your car’s check engine light is on, but the engine still runs fine. Only this time, the warning isn’t about fuel or oil. It’s about your heart.

It’s most common in people over 65. One study found nearly 1 in 6 adults over 75 have it. Often, it’s caused by a toxic nodular goiter-a few overactive lumps in the thyroid-or by taking too much thyroid medication after being treated for hypothyroidism. Less often, it’s from Graves’ disease. The key is that it’s persistent. One low TSH reading doesn’t count. Doctors look for at least two or three low readings over months to confirm it’s real.

Why the Heart Is the Main Concern

The heart doesn’t like being pushed too hard, even gently. Subclinical hyperthyroidism doesn’t make your heart race all day like overt hyperthyroidism does. But it changes how it beats, how it relaxes, and how long it takes to recover between beats.

Studies show people with TSH below 0.1 mIU/L have more than double the risk of atrial fibrillation-a chaotic, irregular heartbeat that can lead to stroke. One analysis of over 8,700 people found those with TSH this low had a 2.5 times higher chance of developing AFib. Even those with TSH between 0.1 and 0.44 mIU/L had a 63% higher risk. That’s not small.

Heart failure risk also climbs. A 10-year study tracking nearly 25,400 people found those with TSH under 0.1 had almost twice the risk of heart failure compared to people with normal thyroid function. In people over 60, the risk of atrial fibrillation triples over a decade. Left ventricular mass increases. The heart muscle thickens. Diastolic function-the heart’s ability to fill with blood between beats-gets worse. Heart rate variability drops, meaning the nervous system’s control over the heart is weakening.

These changes don’t always cause symptoms. That’s why they’re dangerous. Someone might feel fine, go about their life, and suddenly have a stroke or need a pacemaker because their heart’s been quietly damaged for years.

Bones and Brain: The Hidden Costs

The heart isn’t the only thing at risk. Bone density takes a hit. When TSH drops below 0.1, the risk of fractures-especially hip and spine fractures-goes up by more than double. This is especially worrying for postmenopausal women and older men who already have lower bone mass.

Cognitive effects are less clear, but some studies point to subtle declines in memory and executive function-things like planning, organizing, and switching tasks-in older adults with long-term subclinical hyperthyroidism. It’s not dementia. But it’s enough to make daily life harder.

Quality of life? Usually fine-if you don’t have symptoms. But if you start feeling tired, anxious, or notice your heart skipping beats, those subtle changes start to matter more.

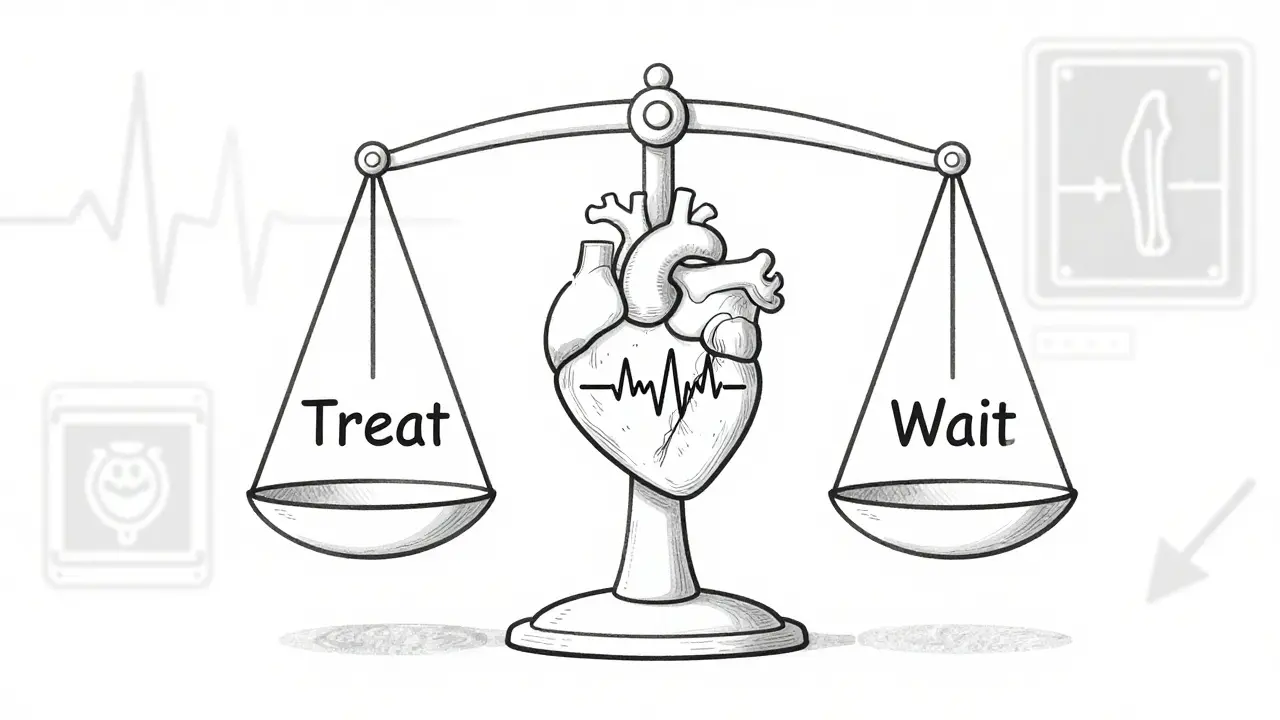

When Should You Treat It?

Not everyone with subclinical hyperthyroidism needs treatment. That’s the big debate. But the guidelines are clear: risk matters more than numbers alone.

If your TSH is below 0.1 mIU/L and you’re over 65, most experts say treat it. Especially if you have high blood pressure, heart disease, osteoporosis, or a family history of atrial fibrillation. Even if you feel fine. The damage is already happening.

If your TSH is between 0.1 and 0.44 mIU/L, treatment isn’t automatic. You need other red flags: symptoms like palpitations, confirmed bone loss, or signs of heart strain on an echocardiogram. If you’re young, healthy, and have no heart issues, doctors might just watch and wait.

First-line treatment? Beta-blockers. They don’t fix the thyroid. But they calm the heart. They lower heart rate, reduce palpitations, and can even reverse some of the thickening of the heart muscle. They’re safe, well-tolerated, and give you time to decide on the next step.

If the cause is a toxic nodule or Graves’ disease, you’ll need to target the thyroid itself. Radioactive iodine is the most common option-it shrinks the overactive tissue. Surgery is less common but used if the thyroid is very large or if you can’t take iodine. The goal isn’t to cure it completely. It’s to bring TSH back into the normal range, not to push it into hypothyroidism.

That’s the tightrope. Treat too aggressively, and you create a new problem: hypothyroidism. That brings its own risks-higher cholesterol, fatigue, weight gain, and even more heart strain. The goal is balance, not perfection.

How Often Should You Be Monitored?

Monitoring isn’t optional. It’s the cornerstone of managing this condition.

- If TSH is below 0.1 mIU/L: Check every 3 to 6 months. Get an ECG and bone density scan if you’re over 65.

- If TSH is between 0.1 and 0.44 mIU/L and you’re low-risk: Check once a year.

- If you’re on beta-blockers: Monitor every 3 months until stable, then every 6 months.

- If you’re on thyroid treatment (like radioactive iodine): Monitor closely for the first 6 months to avoid overshooting into hypothyroidism.

Don’t forget your doctor should also check your heart. An echocardiogram every 1 to 2 years is wise if your TSH is persistently low. A bone density test (DEXA scan) is recommended for women over 65 and men over 70 with suppressed TSH.

What’s Changing in 2026?

Guidelines are shifting. The American Thyroid Association’s 2016 advice was conservative. But newer data is pushing doctors to act sooner.

The DEPOSIT study, tracking 5,000 older adults across Europe, is wrapping up in 2026. Early results suggest even mild TSH suppression (0.1-0.44) increases heart risk in people with existing heart disease. That could change who gets treated.

The THAMES trial, led by UCLA, is comparing outcomes in patients with TSH under 0.1 who are treated versus those who aren’t. Results expected in late 2024 could finally give us randomized proof that treating early saves lives.

The American Heart Association is calling for more trials. They’re tired of guessing. They want hard data to answer one question: Does treating subclinical hyperthyroidism reduce heart attacks, strokes, and deaths?

Right now, the answer is: probably yes-for high-risk people. But we’re getting closer to knowing exactly who benefits most.

What Should You Do Now?

If you’ve been told you have subclinical hyperthyroidism:

- Don’t panic. You’re not alone. Millions have it.

- Don’t ignore it. Especially if you’re over 65 or have heart disease.

- Ask for an ECG and an echocardiogram.

- Ask about a bone density scan if you’re a woman over 65 or a man over 70.

- Ask if beta-blockers make sense-even if you feel fine.

- Ask why your TSH is low. Is it from medication? A nodule? Graves’?

- Don’t rush into radioactive iodine unless you’re high-risk.

It’s not about fixing a number. It’s about protecting your heart, your bones, and your future. Subclinical hyperthyroidism doesn’t roar. It whispers. But if you listen, you can stop it before it breaks something.

Can subclinical hyperthyroidism go away on its own?

Sometimes, yes. In younger people with mild TSH suppression (0.1-0.44 mIU/L), especially if caused by temporary inflammation or medication changes, levels can normalize without treatment. But in older adults, especially with nodules or Graves’ disease, spontaneous recovery is rare. Persistent suppression for more than 6 months usually means it won’t fix itself-and the heart risks keep building.

Does subclinical hyperthyroidism cause weight loss?

Usually not. That’s what makes it different from overt hyperthyroidism. In overt cases, you lose weight, feel hot, shake, and have diarrhea. In subclinical cases, your T4 and T3 are normal, so your metabolism stays balanced. You might feel a little more tired or anxious, but dramatic weight loss isn’t typical. If you’re losing weight unexpectedly, your doctor should check for other causes.

Is radioactive iodine safe for older adults?

Yes, but carefully. Radioactive iodine is the most common treatment for toxic nodules in older adults. It’s non-invasive and effective. But the goal isn’t to make you hypothyroid. Doctors aim for a TSH in the low-normal range, not zero. After treatment, you’ll need lifelong thyroid hormone replacement and regular blood tests. The risk of heart problems drops significantly after successful treatment, especially if you had atrial fibrillation.

Can I just take beta-blockers and not treat the thyroid?

For some people, yes. Beta-blockers are excellent for managing heart symptoms-palpitations, high heart rate, tremors. They don’t fix the root cause, but they protect your heart while you decide. This is common in older adults who aren’t candidates for radioactive iodine or surgery. But if the cause is a toxic nodule, the thyroid will keep overproducing. Eventually, the heart damage may progress. Beta-blockers buy time, not a cure.

Should I get tested for subclinical hyperthyroidism if I’m under 60?

Routine screening isn’t recommended under 60 unless you have symptoms, a family history of thyroid disease, or you’re on thyroid medication. But if you’ve had unexplained atrial fibrillation, osteoporosis, or rapid heart rate with no other cause, testing your TSH is a smart move. Even young people can have toxic nodules. Don’t assume it’s only an older person’s problem.

What happens if I don’t treat it?

If your TSH is below 0.1 and you’re over 65, the risk of atrial fibrillation and heart failure increases significantly over time. Fractures become more likely. Some people live for years without symptoms-but by the time they feel something, the damage may already be done. The longer you wait, the harder it is to reverse. Treatment isn’t about being perfect. It’s about preventing irreversible harm.

All Comments

veronica guillen giles January 4, 2026

So let me get this straight-we’re supposed to medicate people just because their TSH is low, even if they feel like a calm, well-rested potato? 🙄 Next they’ll want us to treat people for having ‘subclinical happiness’ because their cortisol is ‘off.’

Ian Detrick January 6, 2026

It’s fascinating how medicine keeps treating numbers like they’re moral judgments. TSH below 0.44? That’s not a disease-it’s a statistical anomaly with a fancy label. The heart doesn’t care about your lab values. It cares about how you sleep, how you move, how you breathe. If you’re not gasping for air at 3 a.m., maybe the real problem isn’t your thyroid-it’s our obsession with quantifying everything until it loses meaning.

We’ve turned prevention into a numbers game. But the body isn’t a spreadsheet. It’s a living system that adapts. Maybe instead of rushing to suppress TSH, we should ask: What’s the person’s life like? Are they stressed? Sedentary? Eating real food? That’s where the real damage-and the real healing-happens.

Brittany Wallace January 6, 2026

I love how this post doesn’t just dump facts-it tells a story. 🫶 The whispering heart, the silent damage… it’s like the thyroid is the quiet friend who’s been holding your secrets too long and finally cracks. And we’re just now learning to listen.

My grandma had this. Felt fine. Didn’t want to ‘do anything.’ Then one day-stroke. No warning. Just… gone. I wish someone had told her back then what this article says now. We owe it to our elders to listen, even when they don’t feel sick.

Palesa Makuru January 7, 2026

Look, I get the science, but this is just Big Pharma’s latest monetization play. Who benefits from turning millions of asymptomatic seniors into ‘patients’? Not them. Not their families. The labs, the endocrinologists, the beta-blocker manufacturers. You’re being sold a problem to sell a solution. And don’t even get me started on radioactive iodine-‘non-invasive’? Please. You’re basically poisoning your own gland and then paying for the rest of your life to replace it. Classic.

Lori Jackson January 7, 2026

Given the documented pathophysiological cascade-TSH suppression → increased cardiac adrenergic tone → elevated left ventricular mass → diastolic dysfunction → fibrotic remodeling-the clinical imperative for early intervention in high-risk cohorts is not merely evidence-based, it’s ethically non-negotiable. Ignoring subclinical hyperthyroidism in the elderly is tantamount to medical negligence. Period.

Wren Hamley January 8, 2026

So your thyroid’s whispering ‘hey, I’m kinda overworked’ and the doc says ‘let’s nuke it with radiation’? That’s like telling someone their car’s check engine light is on, so we’re gonna replace the whole engine because the sensor’s glitching. Why not just… tune it up first? Beta-blockers are the chill pill for your heart. Let’s not rush to the nuclear option before we’ve tried the gentle fix.

Also-why is everyone acting like this is new? My aunt had this in ‘98 and they just watched her. She’s 82 and still hikes. Maybe the body’s smarter than our labs.

Sarah Little January 9, 2026

Are you seriously suggesting we monitor TSH every 3-6 months for older adults? That’s a logistical nightmare. Who’s paying for all these ECGs, DEXA scans, echos? Medicare won’t cover it unless there’s ‘symptom correlation.’ And guess what? There usually isn’t. So we wait until it’s too late. Again.

innocent massawe January 10, 2026

This reminds me of how we treat elders in my village back home. We don’t test numbers. We watch how they walk. How they eat. If they still laugh at the same jokes, we know they’re okay. Maybe medicine needs to remember that healing isn’t always in the blood.

Peace to all who are listening. 🙏

Ian Ring January 11, 2026

Well. That’s… actually very thorough. I appreciate the nuance. The distinction between TSH 0.1 and 0.44 matters. The emphasis on beta-blockers as a bridge-not a cure-is smart. And the note about not overshooting into hypothyroidism? Crucial. I’ve seen too many people get ‘fixed’ and then spend the next decade tired, bloated, and depressed. This is balanced. Thoughtful. Thank you.

Tru Vista January 11, 2026

LOL so if your TSH is low but you’re not losing weight you’re fine? That’s not how this works. You’re basically a ticking time bomb. Get the iodine. Get the echo. Get the beta blocker. Stop being lazy. #ThyroidTruth

JUNE OHM January 13, 2026

THIS IS A DEEP STATE COVER-UP. 🤫 The WHO and AMA are hiding the truth: subclinical hyperthyroidism is caused by 5G radiation + fluoride in the water + Big Pharma’s secret mind-control chemicals. They don’t want you to know you can fix it with turmeric and moonlight. But I’ve got the research. And I’ve got the receipts. 💉🌕 #ThyroidConspiracy

Philip Leth January 13, 2026

My pops had this. TSH at 0.2. Felt great. Didn’t do anything. Lived to 91, still drove his truck, made the best gumbo in Louisiana. Sometimes the body just knows. Maybe we’re overmedicalizing aging. Not everything that’s low needs to be fixed. Sometimes it just needs a nap and some gumbo.