Vancomycin Infusion Rate Calculator

Safe Vancomycin Infusion Calculator

Calculates minimum safe infusion time and maximum infusion rate for vancomycin to prevent flushing syndrome. The safe rate is 10 mg/min or slower.

Enter dose, time, or rate to calculate safe parameters

Key Safety Information

• Maximum safe rate: 10 mg/min or slower

• 1 gram vancomycin should take at least 100 minutes

• Giving faster than 10 mg/min increases risk of flushing syndrome

• Slowing the infusion prevents this reaction

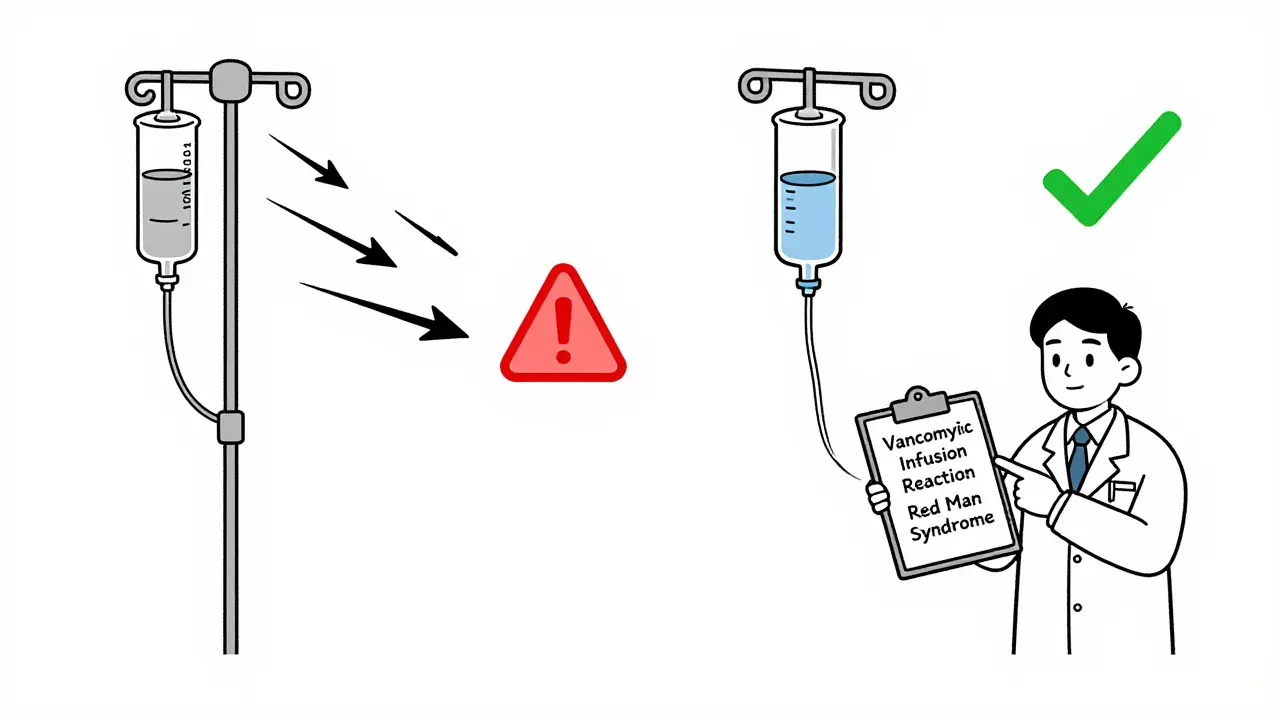

When vancomycin is given too quickly, it can trigger a reaction that makes patients turn red, feel itchy, and sometimes drop their blood pressure. For years, this was called red man syndrome. But that term is outdated, offensive, and medically inaccurate. Today, it’s properly called vancomycin infusion reaction or vancomycin flushing syndrome. And understanding it isn’t just about recognizing symptoms-it’s about preventing a reaction that can be stopped before it starts.

What Exactly Is Vancomycin Infusion Reaction?

Vancomycin infusion reaction (VIR) is not an allergy. It doesn’t involve your immune system remembering the drug from a past exposure. Instead, it’s an anaphylactoid reaction-meaning your body releases histamine directly from mast cells and basophils, like a fire alarm going off without a real fire. This causes flushing, itching, and redness, usually on the face, neck, chest, and upper back.

The reaction happens fast. Symptoms typically show up 15 to 45 minutes after you start the IV drip. You might feel warmth, tingling, or a burning sensation. Your skin turns bright red, especially around your upper body. Some people get a headache, dizziness, or muscle tightness in the chest or back. In rare cases, blood pressure drops or heart rate spikes. But unlike true anaphylaxis, you won’t get swelling of the throat, wheezing, or trouble breathing-unless something else is going on.

Here’s the key: this reaction is almost always caused by how fast the drug is pushed into your vein. Giving 1 gram of vancomycin over 30 minutes? High risk. Spreading it out over 100 minutes? Almost no risk.

Why the Name Changed

“Red man syndrome” was a misleading, racially charged term that stuck around for decades. It painted a picture of a “red man” that had nothing to do with the actual condition-and everything to do with harmful stereotypes. In 2021, a study at a major U.S. children’s hospital found that over 60% of electronic medical records still used the outdated term, even though it was misleading and offensive. After a formal push to replace it with “vancomycin flushing syndrome,” usage dropped by 17% in just three months. Major institutions like UCSF and the Infectious Diseases Society of America now require the new terminology in all clinical notes, prescriptions, and patient education materials.

The change isn’t just about politeness. It’s about accuracy. Calling it a “syndrome” implies a fixed pattern. But it’s not a syndrome-it’s a predictable, preventable reaction tied to infusion speed. Using the right term helps doctors focus on the real issue: infusion rate.

Who Gets It and How Often?

It’s not rare. A landmark 1988 study showed that 82% of healthy adults developed a reaction when given 1 gram of vancomycin over just one hour. None had a reaction when the same dose was given slowly. Even today, with better practices, it still happens-especially in hospitals where staff are rushed or new to giving vancomycin.

Some people are more likely to react: those with a history of the reaction before, patients on multiple medications that trigger histamine release (like opioids or muscle relaxants), and those with kidney problems who need slower dosing anyway. But here’s the surprising part: if you’ve had it once, you’re less likely to get it again. Studies show that with repeated exposure, the body seems to build a kind of tolerance. The second time you get the same dose slowly, the reaction is often milder-or gone entirely.

How to Prevent It

The best treatment for vancomycin infusion reaction? Don’t let it happen in the first place.

- Slow it down. Never give vancomycin faster than 10 mg per minute. That means 1 gram should take at least 100 minutes. Many hospitals now set their IV pumps to run at 15-20 mg/min as a safety limit, but 10 mg/min is the gold standard.

- Avoid other triggers. Don’t give vancomycin at the same time as opioids, muscle relaxants, or contrast dye. These can make histamine release worse.

- Pre-medicate only if needed. You don’t need to give antihistamines like diphenhydramine before every dose. Only use them for patients who’ve had a reaction before and need a faster infusion for medical reasons. Even then, combine it with an H2 blocker like ranitidine for better results.

- Monitor closely. Watch the patient for the first 10-15 minutes after starting the infusion. That’s when symptoms usually begin.

There’s no need to pre-medicate someone who’s never had a reaction. Doing so adds unnecessary drugs, costs, and risk-without benefit.

What to Do If It Happens

If flushing or itching starts during the infusion:

- Stop the infusion immediately.

- Check the patient’s vital signs-blood pressure, heart rate, oxygen levels.

- Call for help if they’re having trouble breathing or their blood pressure drops.

- Once symptoms are under control, you can restart the infusion at a slower rate-usually half the original speed.

- Document it clearly: “Vancomycin infusion reaction, resolved after slowing rate.” Not “allergy.”

Most reactions fade within 20-30 minutes after stopping the drip. No long-term damage. No need for epinephrine unless there’s true anaphylaxis-which is extremely rare with vancomycin.

Differentiating from Real Allergies

Vancomycin can cause true allergic reactions too-but they’re rare. True anaphylaxis involves swelling, wheezing, low blood pressure, and can be deadly. It’s IgE-mediated, meaning your body has been sensitized before. Less than 3% of patients labeled as “allergic to vancomycin” actually have this.

Other serious reactions like DRESS, Stevens-Johnson, or toxic epidermal necrolysis are even rarer. These involve blistering skin, fever, organ damage, and need immediate specialist care. They’re not related to infusion speed.

That’s why labeling every flushing reaction as an “allergy” is dangerous. It can lead to unnecessary avoidance of vancomycin-forcing doctors to use less effective or more toxic antibiotics. In one study, 4% of patients with vancomycin “allergies” had other serious drug reactions, but over 90% had the infusion reaction-which is completely manageable.

Other Drugs That Do the Same Thing

Vancomycin isn’t alone. Other antibiotics and drugs can trigger similar histamine release:

- Amphotericin B - used for serious fungal infections. Causes flushing and low blood pressure via complement activation.

- Rifampin - can cause rash and itching due to reactive metabolites binding to proteins in the body.

- Ciprofloxacin - less common, but has been linked to flushing reactions.

If a patient reacts to one of these, watch for similar patterns: rapid infusion, upper body redness, no respiratory distress. The fix is the same-slow down the drip.

What’s the Bottom Line?

Vancomycin is a powerful, life-saving antibiotic. But giving it too fast can cause a reaction that’s scary, avoidable, and often mislabeled. The solution isn’t more drugs, more tests, or more fear. It’s simple: slow the infusion.

Every time vancomycin is given, ask: “How fast is this running?” If it’s faster than 10 mg per minute, it’s too fast. If the patient turns red, don’t assume it’s an allergy. Slow it down. Monitor. Reassess. Most of the time, you can keep giving the drug safely.

And if you hear someone say “red man syndrome”? Correct them. Say “vancomycin infusion reaction.” It’s more accurate. It’s more respectful. And it leads to better care.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is vancomycin infusion reaction the same as an allergy?

No. A true allergy involves your immune system and requires prior exposure. Vancomycin infusion reaction is caused by direct histamine release from cells, not an immune response. It can happen the very first time you get the drug. Calling it an allergy can lead to unnecessary avoidance of vancomycin, which is often the best treatment for serious infections like MRSA.

Can I still get vancomycin if I had a reaction before?

Yes. Many patients who had a reaction during a fast infusion can safely receive vancomycin again-if it’s given slowly. Studies show reactions become milder or disappear with repeated slow infusions. The key is not to avoid the drug, but to give it correctly.

Do I need to take antihistamines before vancomycin?

Only if you’ve had a reaction before and need the drug given faster than recommended. For most patients-especially first-time users-pre-medication adds no benefit and increases side effects. Slowing the infusion is more effective and safer than adding extra drugs.

How long should a vancomycin infusion take?

A standard 1-gram dose should be infused over at least 100 minutes, or no faster than 10 mg per minute. For patients with kidney issues or a history of reaction, even slower rates (e.g., 150-200 minutes) may be used. Never rush it.

Why is the term ‘red man syndrome’ considered offensive?

The term implies a racial stereotype and has no medical basis. It reduces a physiological reaction to a caricature. Major medical organizations, including the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, have called for its replacement with accurate, non-discriminatory language like “vancomycin infusion reaction.”

Can vancomycin cause long-term damage from a flushing reaction?

No. Vancomycin infusion reactions are temporary and resolve completely within 30 minutes of stopping the drip. There’s no evidence of lasting skin damage, organ injury, or increased risk of future problems. The only real danger is misdiagnosing it as an allergy and switching to a less effective antibiotic.

All Comments

Lori Anne Franklin December 27, 2025

i just had a patient turn red during vanco and i thought we were gonna lose him 😅 turns out we just needed to slow it down. so simple. why do we still make this so complicated?

Bryan Woods December 28, 2025

The terminology shift from 'red man syndrome' to 'vancomycin infusion reaction' is not merely semantic-it reflects a broader commitment to evidence-based, patient-centered language in clinical practice. Precision in nomenclature enhances diagnostic clarity and reduces cognitive bias.

Ryan Cheng December 29, 2025

If you're giving vanco faster than 10 mg/min, you're not being efficient-you're being reckless. I've seen nurses rush it because they're behind on rounds. But slowing it down doesn't take that much extra time, and it saves you from a whole mess of paperwork and panic. Just do it right the first time.

wendy parrales fong December 29, 2025

i love how something so simple-like slowing down an iv-can fix so much. no new drugs, no fancy machines, just patience. reminds me that sometimes the best medicine is just taking a breath and doing it right.

Jeanette Jeffrey December 30, 2025

Wow. Another woke medical buzzword. Next they'll call pneumonia 'lung joy syndrome' because someone found the word 'pneumonia' too harsh. This isn't progress-it's performative language policing disguised as education.

Shreyash Gupta January 1, 2026

i think this is all just overthinking 🤔 also why do we even use vanco anymore? i heard it's bad for kidneys and also makes you sleepy 😅 maybe just use azithromycin for everything? 🙃

Ellie Stretshberry January 3, 2026

i used to think vanco reactions were allergies till i saw one up close... turns out you just gotta go slow and it goes away. no big deal. i always forget to tell new nurses this though lol

Zina Constantin January 3, 2026

I'm from a country where vancomycin is still given in 30 minutes because 'it's faster'. We need more global education on this. It's not just about terminology-it's about saving lives with basic, low-cost practices. Let's stop letting ignorance kill.

Dan Alatepe January 4, 2026

yo i saw a guy turn red like a tomato during vanco and i thought he was having a stroke 😱 then the nurse just slowed the drip and he was fine 10 mins later. like... why do we even panic? it's not magic. it's just chemistry. chill out.

Angela Spagnolo January 6, 2026

I... I didn't know this was preventable... I've seen so many patients get labeled 'allergic' and then they can't get the best treatment... and it's all because nobody slowed the IV... I feel so guilty now...

christian ebongue January 7, 2026

so the solution is... don't be a dumbass and push it fast? revolutionary.

jesse chen January 8, 2026

I've had patients who were terrified to get vancomycin because they were told they were 'allergic'... and then we just slowed it down and they got better. It's heartbreaking how often we mislabel things and then patients suffer because of it.

Joanne Smith January 10, 2026

The real tragedy? Hospitals still don't have alerts in their EHRs to warn when vanco is ordered with a fast infusion rate. We have alerts for penicillin allergies, but not for this? That's not a glitch-it's negligence.

Prasanthi Kontemukkala January 11, 2026

I remember when I first started nursing, I gave vanco in 45 minutes because I thought 'it's just one dose'. The patient turned red and cried. I felt awful. But the charge nurse just said, 'Slow it next time, and you'll be fine.' That moment changed how I do everything now. It's not about speed-it's about care.

Sarah Holmes January 12, 2026

This is exactly why modern medicine is collapsing under the weight of performative virtue signaling. You replace a clinically descriptive term with a euphemism, and suddenly we're supposed to believe the underlying physiology has changed? You're not fixing the problem-you're hiding it behind politically correct language. This is dangerous.