When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how do regulators know it’s safe and effective? The answer lies in a quiet but powerful rule: the 80-125% rule. It’s not about how much active ingredient is in the pill. It’s not even about how strong the drug feels. It’s about what happens inside your body after you swallow it.

What the 80-125% Rule Actually Means

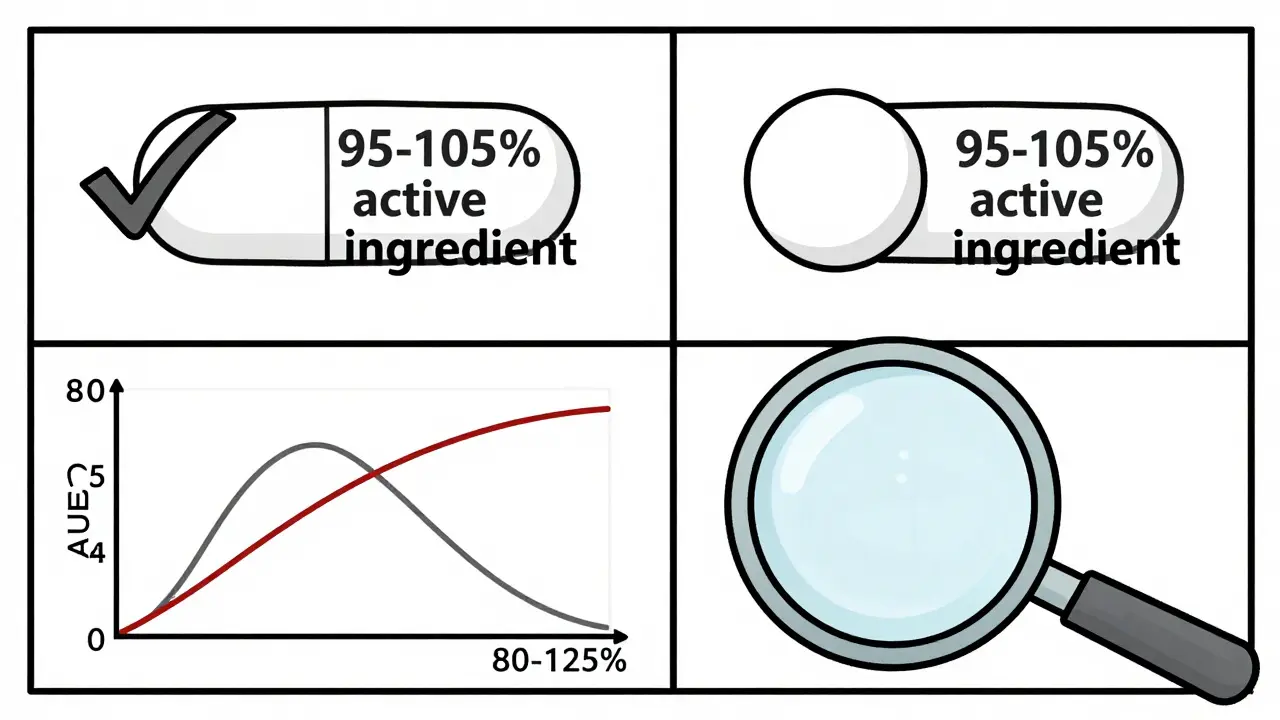

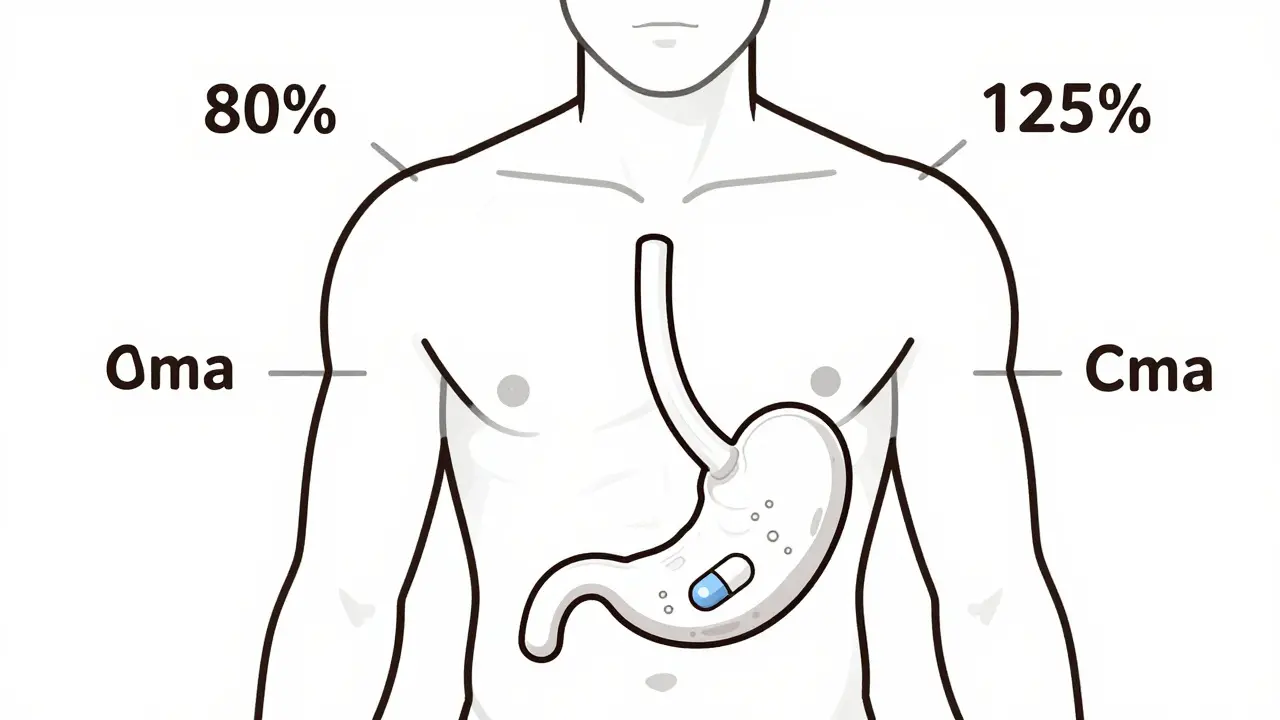

The 80-125% rule is a global standard used by the FDA, EMA, WHO, and other health agencies to decide if a generic drug is bioequivalent to its brand-name counterpart. Bioequivalence means the generic drug delivers the same amount of active ingredient to your bloodstream at the same rate as the original. If it doesn’t, the drug might not work-or it could cause side effects. Here’s the catch: the rule doesn’t say the generic contains 80% to 125% of the active ingredient. That’s a common myth. In reality, both brand and generic pills must contain 95% to 105% of the labeled amount. The 80-125% range applies to the measured exposure in clinical studies-specifically, the ratio of two key numbers: AUC and Cmax. AUC (Area Under the Curve) tells you how much of the drug your body absorbs over time. Cmax (maximum concentration) tells you how fast it gets there. These aren’t theoretical values. They’re measured in real people-usually 24 to 36 healthy volunteers-who take both the brand and generic versions in a crossover study. Blood samples are taken over hours, and the data is analyzed statistically. The 90% confidence interval of the geometric mean ratio of these values must fall entirely between 80% and 125%. That’s it. If even one point of that interval dips below 80% or rises above 125%, the drug fails bioequivalence. No approval. No market.Why Logarithms and Geometric Means?

You might wonder why we don’t just compare average blood levels directly. The reason is simple: drug concentrations in the blood don’t follow a normal bell curve. They follow a log-normal distribution. That means most values cluster near the lower end, with a long tail stretching toward higher values. To make this data manageable, scientists take the natural logarithm of each AUC and Cmax value. On this log scale, a 20% decrease and a 20% increase look symmetrical. A 20% drop from 100 to 80 is the same distance from 100 as a 20% rise to 125. That’s why the range is 80-125%-it’s the log-transformed version of ±20%. The 90% confidence interval is used instead of the more common 95% because it allows for a 5% error on each end, totaling 10% overall. This is a deliberate trade-off. It balances statistical rigor with real-world safety. If you used a 95% CI, you’d need far more participants, making studies prohibitively expensive and slow.Why This Rule Exists: A History of Safety

Before the 1980s, regulators used looser rules. One called the “75/75 rule” required 75% of subjects to have test-to-reference ratios within 75-133%. It was messy. Too many generics slipped through that didn’t behave the same way in the body. In 1986, the FDA held a landmark hearing. Experts reviewed data from hundreds of studies and concluded: a 20% difference in exposure is unlikely to cause clinical problems in most patients. That’s when the 80-125% rule was born-not from a lab experiment, but from clinical judgment. As Dr. Lawrence Lesko of the FDA once said, it was based on experience, not hard data. But over 35 years of real-world use have proven it works. Post-marketing data is telling. Between 2003 and 2016, the FDA approved over 2,000 generic drugs. Only 0.34% required label changes due to bioequivalence concerns. That’s fewer than 1 in 300. Most safety issues came from manufacturing problems, not the 80-125% rule itself.

When the Rule Isn’t Enough

The 80-125% rule is a blunt tool. It works well for most drugs-but not all. Take narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs. These are medications where even a small change in blood level can be dangerous. Warfarin, levothyroxine, and some anti-seizure drugs fall into this category. For these, regulators now require tighter limits: 90-111%. The FDA issued draft guidance for this in 2022. The European Medicines Agency has already adopted it. Then there are highly variable drugs. Some drugs are absorbed wildly differently from person to person. If the reference product’s within-subject coefficient of variation is above 30%, the 80-125% rule becomes too strict. That’s where scaled average bioequivalence (SABE) comes in. It lets the acceptance range widen-sometimes up to 69.84-143.19%-but only if the drug’s variability is proven to be high. The EMA has used this since 2010. The FDA is catching up. And then there are complex products: inhalers, topical creams, extended-release tablets. These don’t dissolve the same way every time. The FDA launched its Complex Generics Initiative in 2018 with $35 million a year to develop new standards. We’re still waiting for the next wave of rules.What Happens in a Bioequivalence Study?

A typical bioequivalence study looks like this:- 24 to 36 healthy volunteers are enrolled.

- They’re randomly assigned to take either the brand or generic drug first, then switch after a washout period (usually 1-2 weeks).

- Blood samples are taken every 15 to 30 minutes for up to 72 hours.

- Researchers measure AUC and Cmax for each drug.

- Data is log-transformed, geometric means are calculated, and the 90% confidence interval is determined.

- If the interval fits within 80-125%, the drug passes.

Why Pharmacists and Patients Get It Wrong

A 2022 survey found that 63% of community pharmacists thought the 80-125% rule meant generics contain less active ingredient. That’s not true. The rule measures what happens after you take it-not what’s in the tablet. Patients see the numbers and panic. Reddit threads, Drugs.com forums, and Facebook groups are full of people afraid their generic seizure medicine is only “80% as strong.” But here’s the truth: if a generic passes bioequivalence, it’s as safe and effective as the brand. The FDA has tracked over 14,000 approved generics in the U.S. Since 2000, 90% of prescriptions are filled with generics-and they’ve saved the system over $300 billion. The real problem isn’t the rule. It’s the misunderstanding. A 2022 study of neurologists found that 28% had seen occasional problems with generic anti-seizure drugs. But only 4% of those were linked to bioequivalence. The rest? Different fillers, coatings, or dissolution rates that affected how the pill broke down in the gut. Those aren’t covered by the 80-125% rule. That’s why some patients need to stick with one brand.The Future: Personalized Bioequivalence?

Right now, the rule treats everyone the same. But we’re moving toward precision medicine. What if your genetics affect how you metabolize a drug? What if you’re a fast metabolizer? A slow one? The 80-125% rule doesn’t care. Emerging research in pharmacogenomics suggests we might one day need bioequivalence standards tailored to genetic subgroups. The FDA’s 2023-2027 plan includes $15 million for “model-informed bioequivalence”-using computer simulations to predict how a drug behaves in different populations. By 2030, we might see rules that say: “This generic is equivalent for CYP2D6 normal metabolizers, but not for poor metabolizers.” For now, the 80-125% rule remains the gold standard. It’s not perfect. But it’s simple, consistent, and proven. It lets millions of people get life-saving drugs at a fraction of the cost. And that’s why, despite all the debate, it’s still here.What You Should Know as a Patient

- The 80-125% rule is about what happens in your body-not how much drug is in the pill. - Generic drugs are not weaker. They’re tested to perform the same way. - If you’re on a narrow therapeutic index drug (like warfarin or levothyroxine), talk to your doctor before switching brands. - If you notice a change in how you feel after switching to a generic, report it. It might not be bioequivalence-it could be a formulation issue. - Don’t let the numbers scare you. The rule is designed to protect you, not trick you.Is the 80-125% rule the same everywhere?

Yes. The FDA, European Medicines Agency, World Health Organization, Health Canada, and over 50 other countries use nearly identical standards. This global alignment makes it easier for drug companies to develop generics that work across borders. Minor variations exist for complex products, but the core 80-125% range for AUC and Cmax is universal.

Do generics have less active ingredient than brand drugs?

No. Both brand and generic drugs must contain 95% to 105% of the labeled amount of active ingredient. The 80-125% rule applies to the body’s absorption of the drug-measured as AUC and Cmax-not the pill’s content. The difference in active ingredient between brands and generics is negligible and tightly controlled.

Why is a 90% confidence interval used instead of 95%?

A 90% confidence interval allows for a 5% error on each side, totaling 10% overall. This balances statistical power with practical feasibility. Using a 95% CI would require far more study participants, making bioequivalence trials too expensive and slow. The 90% CI has been validated over decades of real-world use and is accepted by global regulators as the right trade-off.

Can a generic fail bioequivalence and still be sold?

No. If the 90% confidence interval for AUC or Cmax falls outside 80-125%, the generic drug cannot be approved. The FDA and other agencies will reject the application. This is a hard cutoff. There are no exceptions for cost, demand, or convenience. Safety and performance come first.

Why do some patients say generics don’t work as well?

Most reports of problems aren’t due to bioequivalence. They’re often caused by differences in inactive ingredients-fillers, coatings, or how fast the pill dissolves. These can affect absorption, especially for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows. If you notice a change after switching, talk to your doctor. It might be worth sticking with one brand, even if both are technically bioequivalent.

All Comments

Howard Esakov January 28, 2026

Oh please. The 80-125% rule? That’s just regulatory theater. 😒 I’ve seen generics that make me feel like I swallowed a brick. Log-normal distribution my ass-my body doesn’t care about your stats, it just knows when something’s off. 🤷♂️

Rhiannon Bosse January 30, 2026

Wait wait wait-so you’re telling me the FDA just *guessed* this number? Like, ‘eh, 20% difference is fine, what’s the worst that could happen?’ Bro, I know my grandma’s thyroid med was switched to a generic and she started hallucinating. Coincidence? Or just the 0.34% they don’t tell you about? 🕵️♀️💊

Bryan Fracchia January 31, 2026

Honestly? This is one of those things that sounds super technical but is actually kind of beautiful. It’s not about perfection-it’s about balance. We’re not trying to make identical pills. We’re trying to make *equivalent outcomes*. And honestly? It’s worked for decades. Sometimes the simplest rules are the most human. 🌱

Lance Long February 2, 2026

I just want to say-thank you for writing this. I’ve been a nurse for 22 years and I’ve seen patients panic over generics because they think they’re ‘weaker.’ This is the kind of clarity we need. You didn’t just explain the rule-you explained why it matters. ❤️

fiona vaz February 3, 2026

The 90% CI point is crucial. People don’t realize that increasing it to 95% would require tripling the sample size. That’s not just expensive-it’s unethical to ask more people to participate if the current standard is proven. This isn’t bureaucracy. It’s smart science.

Brittany Fiddes February 3, 2026

Oh so now the Americans get to decide what’s ‘safe’ for the whole world? 🇺🇸😂 The EMA’s been tightening things for years while the FDA still clings to 1986 logic. If you think 125% is acceptable for warfarin, you’re either delusional or on Big Pharma’s payroll. #BritishScienceWins

Colin Pierce February 4, 2026

I’ve worked in pharma QA for 15 years. The real issue isn’t the 80-125% rule-it’s the fillers. One generic had a different coating that slowed dissolution just enough to make patients feel ‘off.’ Not bioequivalence failure. Formulation quirk. Always check the manufacturer.

Ambrose Curtis February 5, 2026

lol so the rule is based on log transforms and geometric means? sounds like someone just wanted to make math look fancy. i mean, if your body absorbs 80% of the drug, that’s still 80% of the drug. why do we need all this jargon? i just want my meds to work. 🤷♂️

SRI GUNTORO February 6, 2026

This is why the West is falling apart. You trust algorithms and statistics over God’s design. If a man needs a pill, he should take the original-created by real scientists, not some lab in India with cheap fillers. This 80-125% nonsense is a sin against healing.

Kevin Kennett February 8, 2026

To everyone panicking about generics: if your life depends on this med, talk to your doc. But don’t let fear stop you from saving hundreds a month. The system’s flawed? Yes. But it’s still the best we’ve got. And if you’re having side effects? Report it. That’s how we make it better.

Kathy Scaman February 10, 2026

I just read this while waiting for my generic Adderall to kick in. Honestly? Feels the same. Maybe I’m just lucky. Or maybe this rule actually works. 🤷♀️

Anna Lou Chen February 10, 2026

The 80-125% rule is a neoliberal epistemological apparatus disguised as pharmacological rigor. It’s not about bioequivalence-it’s about commodifying therapeutic outcomes under the guise of statistical normalization. The log-transformed geometric mean is a Foucauldian biopower mechanism that pathologizes individual metabolic variance in service of capitalist efficiency. 🧠💸